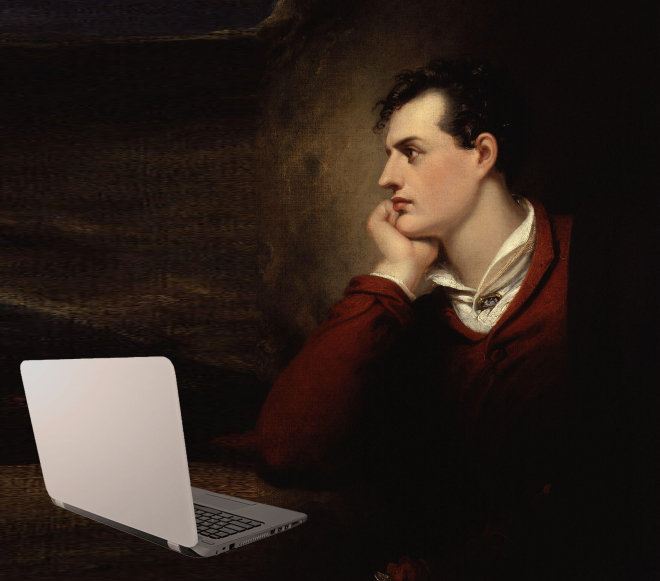

Lord Byron at his computer

Lord Byron at his computer

By Bob Holman and Steve Zeitlin

John Keats might have called the computer “a thing of beauty.” Or perhaps “an unravish’d bride of quietness.” Coleridge’s question, “Is very life by consciousness unbounded?” could just as aptly apply to the computer.

What Byron, Shelley, Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Keats did with pen and paper is still accessible 200 years later. But can our new computers help us write in the style of the Romantics? Can the zeros and ones of digital technologies collaborate with us to write poetry? Bob Mankoff, cartoon editor of Esquire, says Yes.

Along with Jamie Brew of the Onion’s satirical website the ClickHole, he founded the app company Botnik, which is “very semi-seriously” looking into this question. Its new app Predictive Writer can harness the vocabularies of Seinfeld episodes, recipes, Bob Dylan, country music, and more to create playful word games that enable you to write in different styles. When you go to the Predictive Writer app, you can select from a number of idiom-specific “keyboards” that the Botnik community has uploaded: Seinfeld season 3, cooking recipes, Savage Love (a syndicated sex-advice column), and the Romantic poets that we ourselves suggested to them. Say you want to write a poem in the style of Keats. You choose the Keats option, enter a word or two into the app, click on the eighteen choices they offer for the next word à la Keats, and on it goes. Try it at apps.botnik.org/writer/. But why, pray tell, would anyone want to do this?

MANKOFF

MANKOFF

Why do some people surf? Certainly not just to get from the water to the beach. Why fall down ten times in the process? Because you want to ride the wave! It’s fun to see if you can surf this chaos of information that is coming at us from all directions, all the time.

HOLMAN

Predictive Writer may be great for writing a meta-Seinfeld, but now Zeitlin wants to challenge the app to a poetry writing episode—a Romantic poem, to be specific—and wants me to be the first poet in history to take a plunge into the ice-cold computer waters and generate a poem with this app. I mean, after all, Seinfeld is famous for being about Nothing, right? Predictive Writer is right there, pure vocabulary. Or you can spice it up by adding some octopus-pancake-recipe language from a different part of the app.

Predictive Writer may be great for writing a meta-Seinfeld, but now Zeitlin wants to challenge the app to a poetry writing episode—a Romantic poem, to be specific—and wants me to be the first poet in history to take a plunge into the ice-cold computer waters and generate a poem with this app. I mean, after all, Seinfeld is famous for being about Nothing, right? Predictive Writer is right there, pure vocabulary. Or you can spice it up by adding some octopus-pancake-recipe language from a different part of the app.

ZEITLIN

We can’t begin to surmise what the Romantics might have made of computers, let alone Botnik’s app. According to Mankoff, it would be akin to asking a fourteenth-century monk what he thinks of Monty Python. (Wait a minute, wasn’t there a fourteenth-century monk in Monty Python?)

We can’t begin to surmise what the Romantics might have made of computers, let alone Botnik’s app. According to Mankoff, it would be akin to asking a fourteenth-century monk what he thinks of Monty Python. (Wait a minute, wasn’t there a fourteenth-century monk in Monty Python?)

HOLMAN

I’ve never been one to shy away from inspiration. Poems make imagination real (don’t forget that).

Some topics of my earliest poems include George Washington following Indian trails (my first poem, age nine), the big natural bump on my foot (first poem for Kenneth Koch, my teacher at Columbia, age nineteen), and Life itself as a Poem (Life Poem, a book-length poem, written when I was twenty-one, will be published by the Operating System in 2018). As I’ve aged, I’ve found inspiration in other poets, Baraka and O’Hara and Stein et al. If I were stuck, I’d just open Kyger and there’d be the word, waiting.

Botnik is like the suggestions your smartphone makes, except instead of being drawn from the domain of general English, they come from the lyrics of Bob Dylan, David Bowie, Leonard Cohen, or Romantic poetry.Then came the computer. The “word processor,” as we first called it, taking a Cuisinart to the dictionary. Tzara and Burroughs used scissors for their cut-ups; we just highlight, hit control+C (Ted Berrigan’s zine?), go to exact point in the poem where we want the text, and hit control+V (Pynchon?) and drop it, you know, wherever.

Which brings us to Botnik and the wonders/horrors of its Predictive Writer software. It’s like the suggestions your smartphone makes, except instead of being drawn from the domain of general English, they come from the lyrics of Bob Dylan, David Bowie, Leonard Cohen, or Romantic poetry. One is expected to just “feel” or randomly strike a letter or two, no thought needed, and then select a word from a grid of up to eighteen choices, insert, and keep going.

MANKOFF

Hey, other Bob (to whom I’m the other Bob): you don’t have it quite right. The process of creating sentences from a specific source with Predictive Writer—whether the source is a poem or anything else—is anything but random. They are the most likely next words from that vocabulary, given the ones you selected. We’re still in the process of developing the app to make it more intelligent in terms of knowing which parts of speech are permitted, as well as layering on more rules of syntax. But the more intelligent it becomes, the more intelligence it will require from humans to turn linguistic anarchy into poetry.

HOLMAN

But, other-other Bob, to come up with anything resembling a Romantic poem, I would need to write not just according to syntax, but also rhyme and meter. So when I found myself stymied by Predictive Writer’s limitations, I resorted to old faithful print rhyming dictionaries (though I could have used one of the many rhyming sites on the Net).

Once I got over my pique, I settled in, using all the tools available—digital, print, or muse—following the predictives to lines on love for Keats and Shelley, using forms and meters familiar to each, with some shadows of larger issues floating like a cloud. (I went with “azure-lidded” regardless. Couldn’t resist.)

ZEITLIN

I shared this essay with the writer Caitlin Van Dusen for her comments, and when she got back to me and I started to reply on my iPhone, the predictive writer on the phone suggested that I write “Thanks for the feedback” or “Awesome, thanks!” How long before the phones can predict our questions as well as our responses?

Botnik’s Predictive Writer is playful, only “semi-serious”—I know that—but it raises some provocative questions about where all this is going. Beyond the storage of information, search engines such as Google and the other ubiquitous apps of our times are so integral to our lives that it is fair to consider them extensions of our brains, expanding our access to knowledge beyond that of any genius who ever lived. But where does the computer end and “I” begin? And think how much more difficult it would be to tell the two apart if a computer chip were installed in each person’s brain—something that anyone with half a brain can see coming.

A computer can take you (virtually) anywhere you want to go, tell you anything you want to know, or, as in the case of this app, access vast databases of language—but a poem you write yourself illuminates who you are. Do we forego our limitations, the way our minds mold and hold memory, when we express ourselves through poems that are wholly or partially computer-generated? Are we the last generation to experience a distinctive, genuine personhood as future generations increasingly integrate their brains with computer programs? Are we the last generation that believes creativity springs eternally from the human breast?

HOLMAN

My writing was well under way—I was creating Romantic poems with the vocabulary of Shelley and Keats—when Steve lay a content demand on me: your Romantic poem, he opined, wants to mirror the consciousness shift you are using and talking about. From pen and paper to the digital world? Whaaaaa?!!

That would have to be Coleridge. But this time, I dictated the poem using Predictive Writer the way I used to use the books of Ashbery—as in: now I need an Ashbery word, now a Hopkins word (“dapple-dawn-drawn”). So when I wanted predictive, I took it; otherwise, folks, the vocabulary is that of the Coleridge I know, not the limited choices available on the current early iteration of the app.

I ended up with twelve lines. I figured if I was this close to a sonnet, why not just close it off with a couplet? But for the final two lines, I’d let Predictive Writer pick the words.

THE ROMANTICS, VIA PREDICTIVE WRITER, ASSISTED BY HOLMAN

Inspiration! Sweet wedding of wind and mind!

How doest pure thought true nature find

From inner mechanics of mind set loose

Upon a field of emptiness, and choose

Amidst the fragment figments, one to fire the page

Kindled by thy clustered raves and rage?

Now tune the fretted future to thy will

Feel the mechanic’s soulless chill

Follow corpus syntax ad infinitum

Borrow from the past and bite them

Harder than a bullet tween thy teeth

Pity the Poem, lost in withered wreath.

ZEITLIN

So Bob did “Bobnik” the poem—and whether the results sound more like Coleridge than Holman, you decide.

But perhaps it’s a bit futile to ask the vocabulary of the Romantics to comment on a digital world they couldn’t possibly conceive of, because, for starters, they simply didn’t have the words for it.

In the movement to revitalize the Hawaiian language in the early twentieth century, a Hawaiian word was needed for “computer.” There were three schools of thought on how to find one: first, go to the elders, who have lived the language; second, go to the linguists, who knew the history of the Hawaiian language; and third, go to the street, where the approach is to take an English word and make it sound Hawaiian.

The issue was ingeniously resolved. The Hawaiians had electricity—and they had the word “brain.” So the elders coined a marvelous term for “computer”: the “electric brain.” Who are we to make of poetry composed in part or in full by an electric brain? Certainly it’s better than the electric chair, but is it limiting or furthering our humanity?

HOLMAN’S ENDING

And what better place to round off the Romantics’ sonnet than with Seinfeld, season 3, “Kramer”?

Go n sweeper george fruit greatest jerry stub

Forever lid bother elaine’s martinizing club

ZEITLIN’S ENDING

Lord Byron: All farewells should be sudden. Force quit.

Bob Holman is the author of 16 poetry collections, most recently Sing This One Back to Me (Coffee House Press). Holman has played a central role in the spoken word and slam poetry movements of the last several decades. His avatar from the New York Times’s “Poetry Pantheon.”

Steve Zeitlin is the founding director of the nonprofit cultural center City Lore and is the author or coauthor of several award-winning books on America’s folk culture. Most recently his is the author of The Poetry of Everyday Life: Storytelling and the Art of Awareness from Cornell University Press. His avatar painted by Brazilian street artist Deçio Fereira.

Share this: