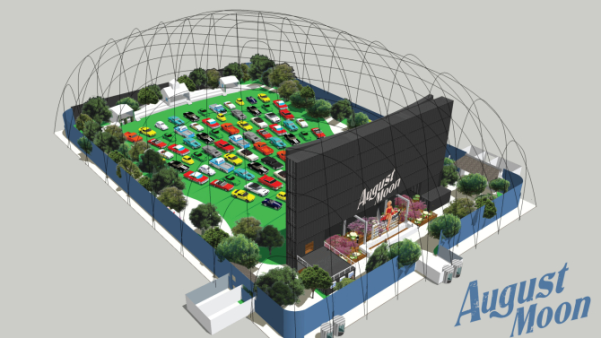

Seen from the air, Las Vegas sprawls out into the desert until it just quits, like it hit an invisible wall. There are no tendrils of settlements trailing away, no outlying development. Just a city where there shouldn’t be one, fueled by the notion that if you build a place in the middle of nowhere and give people unlimited access to squander their fortunes, then people will come and throw so much money at that place, it will resemble the jewel of a thousand-year empire. And there are not many movies that capture the inner workings of this city’s early, mob-driven days than Martin Scorcese’s crime epic, Casino.

The story focuses on Sam Rothstein, a mafia bookmaker who gets sent out to Las Vegas to run the Tangiers casino, a place owned by a corrupt teamsters union that is, in turn, run by the mob. The idea is for the mob to skim off the top of the casino’s profits, but Sam doesn’t really care; he’s a gambler’s gambler and he runs the Tangiers like a well-oiled machine, making it one of the most profitable betting houses in Las Vegas. He is so successful that the bosses send Sam’s childhood friend—and enforcer—Nicky Santoro out West to make sure nothing happens to Sam. Meanwhile, Sam falls in love with a hustler named Ginger McKenna, convinced he can cure her of her grifting ways. And it all works for a while until Nicky’s violent mania leaves bodies everywhere, Ginger’s drinking and conniving create huge personal issues for Sam, and Sam himself gets in a very public squabble with the law that threatens the very operation of the Tangiers itself. As things begin to fall apart in rapid fashion, one fact remains lurking in the background: there are an awful lot of shallow graves in the deserts outside of Las Vegas…and there is always room for more.

This movie feels very much like a spiritual success to Scorcese’s Goodfellas, both in cast (Robert DeNiro and Joe Pesci starred in both movies) and in story; a long-form biopic of the rise and fall of a prominent figure in the criminal underworld. Marked by ongoing narrations by both Sam and Nicky, Casino repeatedly violates the writing rule of “show, don’t tell,” but you never really mind because it’s all done so well. That can be said for the entire film, really. On paper, this movie shouldn’t work. It’s too close to other crime epics, its central dramas are predictable, its violence is excessive, and the characters are all various underworld stereotypes.

And yet, this movie works splendidly well thanks to its direction, cinematography, acting, and editing. This is a movie where it doesn’t matter if you know 30 minutes in that every person in this story is going to die or end up in jail, because watching it unfold is so incredibly satisfying. There is a great pleasure to be had in seeing master artisans ply their trade, and here, everyone involved is running at the height of their powers in a movie so polished that it gleams. And that goes double for the movie’s long expository sequences, which provide the audience with a fascinating crash course in how a totally corrupt casino operates.

In one such scene, we see how it is that Sam rises to his height of power. Relentlessly monitoring every aspect of the gaming house’s operation, nothing escapes his scrutiny, whether it’s how many blueberries the kitchen is serving in its muffins, or whether or not cheaters are trying to rip the place off. On that latter front, Sam is alerted to a player winning too much, and Sam sniffs a rat. He spots the guy’s partner who is helping him cheat at cards. With a few terse phone calls, Sam arranges for the cheating partner to get hit with a cattle prod and taken off the floor—all without tipping his hand to the other players. Backstage, the guy is tortured to make an example for all others to follow: come to the Tangiers and try any shenanigans, you will get caught, you will get punished, you will get scarred for life. And then Sam goes back to work without pause. For all we know, he does the same thing three more times that night.

And that is the best part of Casino: watching Sam work like an inhuman game-making machine while in the background he is juxtaposed by the savage exploits of his friend Nicky, who robs, assaults and kills his way across Las Vegas in an endless spree that only persists because the cops in the city are marginally less crooked than Nicky is. In a mob movie, you expect random violence, vulgar brutality, and no honor among thieves. And you see it here, too. But Sam sits on top of it all, exerting a weird kind of order upon the natural chaos of organized crime—an oxymoron if ever there was one. And it’s kind of amazing to see.

The moment of truth comes when Sam undoes himself, though, by the same precepts that make him such a good casino manager. Too convinced in the logic and method of his operations, he refuses to do a small favor asked of him by the county gaming commissioner. The ask is small: to reinstate an incompetent—but well-connected—employee. Sam can’t do it; he respects skill and efficiency too much to let some nimrod back into his house, even if it’s at a job “further down the trough,” as it were. The commissioner vows revenge, and he most definitely gets it, setting off the chain of events that will eventually destroy the Tangiers, Sam, Nicky, Ginger and even the mob bosses back home. Sam is so smart, it’s scary. But nobody is so smart that they don’t run the risk of being too smart for their own good. Especially in Las Vegas.