At Christmastime, I often hearken back to Simple Gifts — a vintage PBS production which has proven a rich source of reflection for me.

I can relate to this Christmas story because it deals with hope and dreams versus harsh reality, and reminds me of an incident from my own childhood.

My father sired me late in life, so when I was ten years old he had already passed his sixtieth birthday. My arrival was not planned, and though he loved me in his own way, my father later confided to me (with some bitterness) that “Mommy stuck me with you.” His genuine love had to struggle against his unpreparedness (due in part to poverty and illness) to become a father, with all the attendant responsibilities.

My father suffered from insomnia, aggravated by physical illnesses, and by worries and sad memories. As a result, by the time I was in elementary school he had taken to sleeping during the day. The flat where we lived was comfortable, but it was a railroad flat with only one bedroom at the far end, where the three of us slept. My bedtime was 9 PM, but my father would sometimes just be arising at that time, and was preverbal in his first hour after waking. So during that portion of my childhood, we lived in the same house, but (sleeping in shifts) had surprisingly little contact.

Still, there were weekends and holidays and other times when our schedules overlapped, and there were happy times when we were together as a family, though these became increasingly rare as my parents approached the breakup point. I can remember a disastrous Thanksgiving with my father posing for a photo as the family patriarch, carving the turkey, and a mocking look on my face like Who is this guy? Any resemblance to a Norman Rockwell poster was disappearing at breakneck speed.

But for the most part, as a child in elementary school I had no sense of normalcy where families were concerned. I lived from moment to moment, accepting things as they were, with very little questioning.

I loved my father with a child’s love, but also feared him for his angry moods. I believed the stories he told me, and came to share in his love of vintage audio equipment, which he would futz around with in our living room (which was the front room) during his waking hours. He had an assortment of old tape recorders and microphones and tuners and amplifers and speakers which he enjoyed hooking up in a variety of ways. I was always fascinated by the infinite possibilities. Making “cable spaghetti” in search of some hitherto undreamt of combination was maybe the most fun I had as a child.

I remember in particular how his old, dying tape recorders made uncharacteristically youthful chirping sounds, as if their innards housed a chorus of newly hatched robins blinking at the capstans and pinch rollers which otherwise inhabited the same wood-and-metal nest. My father, however, thought more in terms of Orthoptera than Erithacus, and referred to the sounds made by these ancient instruments as “crickets.” Though never entirely absent, the cricket sounds sometimes became especially pronounced, and then my father would curse those “goddamn crickets,” and proceed to take apart and put back together the offending recorder, usually with no noticeable improvement. But I suppose it provided him with the much-needed illusion of work, as my own tinkerings with computers do today.

Isopropyl alcohol in tiny vials, Q-tips, and 3-In-One oil were the liniments my father routinely applied to any dead-man-walking gizmo located within his dominion. Some, perhaps several of such gizmos owe to him a few added months or years of life lived in a kind of techno limbo between functioning and non-functioning — a questionable form of Grace arising from his limited repertoire of home remedies for ailing mimetic devices.

While sitting idly and blowing smoke from Pall Malls which he smoked from a holder, my father would fill my head with stories about 45th Street in Manhattan, where all the electronics stores were located. I had never been to 45th Street, but as a budding technophile I could picture them all lined up, filled with an unending supply of alligator clips and speaker wire and phono plugs, and massive woofers pumping out earth-shaking bass tones, and tiny titanium tweeters supplying the highs — highs I was vicariously in search of.

(Dim rumours reached our household now and then of a new development called stereo, but as all my father’s equipment was antiquated, hand-me-down mono gear, we rejected such rumours and lived in our own heavily insulated monophonic bubble. And though my father died in 1980, I don’t believe he ever succumbed to the stereo fad.)

I remember a Father’s Day in the fourth grade when we pupils were asked to create an art project using scratch art — the kind where you scratch out the black to leave a line drawing in coloured crayon.

An example of children’s scratch art, or crayon etching

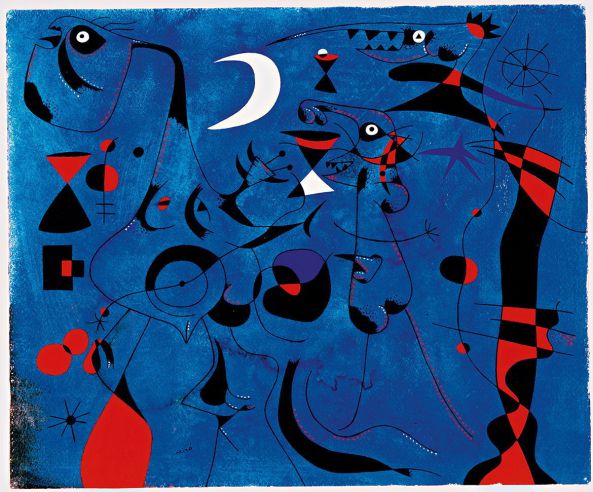

Mine (lost long ago) was inspired by the one area where my father and I still pleasantly interacted. It was no Precisionist masterpiece, or even of mechanical drawing quality. With its cable spaghetti flying in every direction, occasionally alighting on a vaguely rectangular object, it was more Abstract Expressionist — possibly something Miró would have banged out, a constellation that never quite made it into the night sky.

One of Joan Miró’s “constellation” pictures, this one titled “People at Night, Guided by the Phosphorescent Tracks of Snails.” Look carefully and in addition to fish and birds, you’ll also see a small likeness of Eleanor Roosevelt.

I don’t recall if my father ever saw or commented on my youthful masterpiece, but I do remember pressure mounting on him to take me to the tech oasis of 45th Street, which he had inflated in my mind, and which I had further inflated with the imagination-power that only ten-year-old boys possess.

Finally, the great day came! My father rose earlier than usual — as early as 3 PM. We departed from home by 4 PM on a cold winter day, as the light was fading. (Did we ride bus or subway? I can’t remember…)

We arrived at the Mecca of 45th Street around 4:30, and the Fairy Lights which lit up my brain were noticeably absent. We managed to visit one or two electronics shops, but it was drawing nigh on five minutes to five, and it began to dawn on me that the Great Transformation of Life which I expected as a result of beholding the Awe and Mystery which was 45th Street had not yet happened, and was not going to happen.

I don’t recall that my father bought anything at either store. I asked wanly whether we would visit more stores, but my father replied matter-of-factly that they were just closing up. He was a fairly cynical person, but perhaps my own imagination had somehow cross-pollinated with his on this occasion, and he too was expecting more from the experience.

Rather than a shared epiphany, this was like a moment of unshared existential sadness — my father realizing that this one short trip wouldn’t make him Best Dad Ever, and me realizing that 45th Street was just another place with shops — human-sized shops not bulging with electronic toys for the taking, and not providing a gateway to Paradise. We both felt let down, but it failed to bring us closer together. We walked onward, each managing his expectations in his own way, and neither outwardly acknowledging defeat.

Of course, this anticlimactic ending was not entirely my father’s fault. True, he could have gotten up earlier, could have planned the trip better, and could have arranged some concrete purchase (however small) which would have made it all seem worthwhile. But much later on in life, in the course of my spiritual studies, I came to understand that it’s the nature of desire that its fulfillment can never compare with the imagined thing. We have an innate core longing which all desires merely animate or focus on small trifles. Experience teaches us that what we crave will not really satisfy us, yet we become accustomed, or habituated, or addicted to fulfilling our desires, in spite of knowing the fruitlessness of their fulfillment.

Had I learned nothing since the days of childhood, I would now be preparing to go to that Big Electronics Store in the Sky. I suppose the modern version would involve cable TV with 10,000 channels, a fully interactive supercomputer, a smartphone with built-in 16-track recording studio, unlimited Internet access with no data caps, and a host of other things that Big Tech promises us in ads, then takes away in the fine print or the doing.

I am fortunate that through reading, study, meditation and dreams, I now look forward to something much more meaningful, and not based on Fairy Lights. But that is another tale, and today’s tale is only a Christmas Story or Winter’s Tale.

My father was a proud and often emotionally inacccessible man. This was true until his death. Like Moss Hart, I was with my father in the period leading up to his death, when he was in a nursing home. Unlike Moss Hart, I can’t claim that we shared a moment of perfect closeness. I do remember a day, sitting quite near to him as he sat in a wheelchair. It was a sunny day, out on the grass, overlooking the river in Riverdale, New York. Running out of things to say, I closed my eyes and meditated on peace. When I opened them again, he too looked peaceful, almost as if meditating. He remarked that it felt peaceful.

I don’t suppose it was more than a month later that he died, and while that moment of shared peace is less than I might have hoped for, it is more than many are granted. I remain grateful for it to this day.

May all be granted Peace at Christmastime, especially those who have shown me kindness beyond my imagination.

* * *

Advertisements Share this: