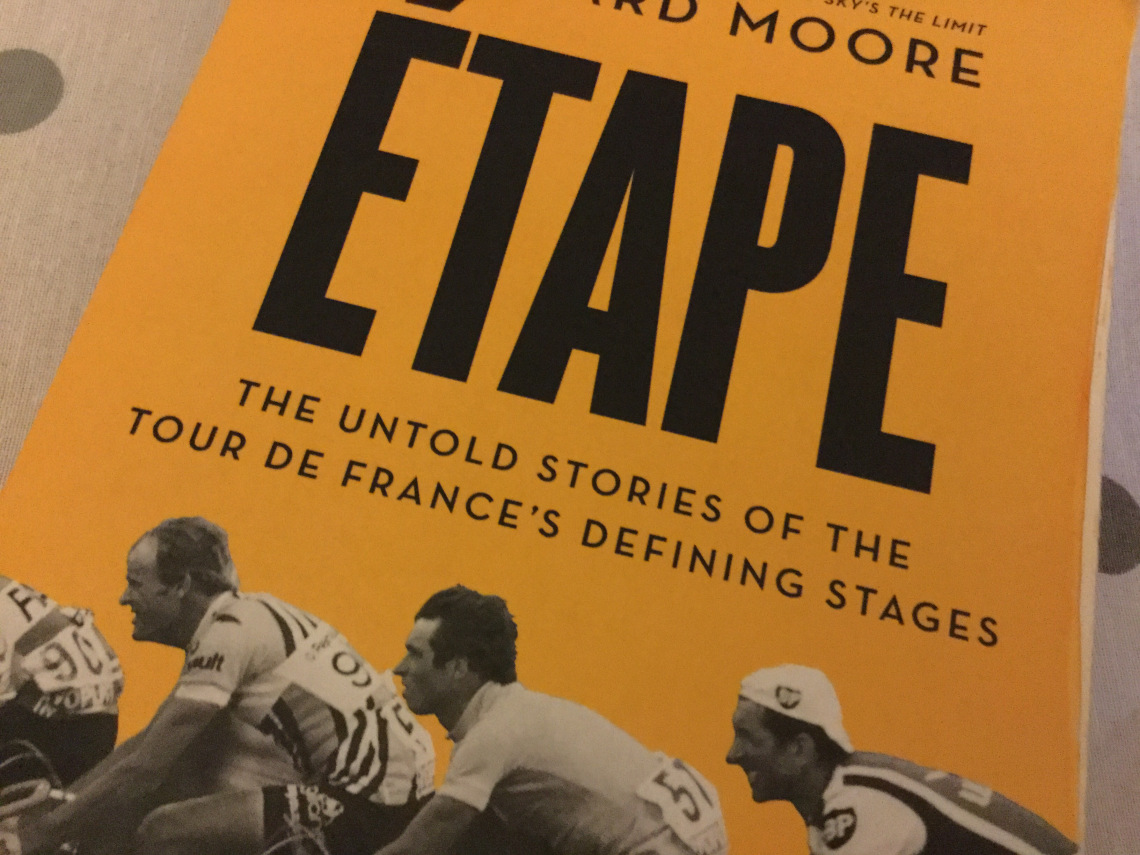

In his book Etape, Richard Moore revisits stages of the Tour de France through the eyes of the protagonists. The first chapter in the book is about Chris Boardman’s win in the Prologue in Lille in 1994, which made him only the second Briton to wear the race leader’s yellow jersey. Boardman’s route into the professional peleton had been an unusual one; he turned professional relatively late, at the age of 25, after winning the individual pursuit at the Barcelona Olympics in 1992, and then breaking the world hour record in Bordeaux in 1993–a record attempt that took place just as the Tour went through the city.

Boardman was invited onto the Tour podium the day after his ride, although not all of the Tour riders were impressed. Luc Leblanc, then the leading French rider, said publicly that most members of the Tour peleton could better Boardman’s distance if they put their minds to it.

Boardman was always quite anxious about his performance, and before Barcelona, he went to see John Syer, a leading sports psychologist.

Prior to the Barcelona Olympics, Boardman spilled out his fears to John Syer. “What if this goes wrong? What if I can’t go fast enough? What if the other guy’s faster? What if I puncture.”

Boardman expected Syer to offer words of reassurance. Instead he said: Yeah, well, those things could happen.” Boardman was puzzled. “I said, ‘Hang on, aren’t you supposed to be helping me here?’ But he said, ‘No, this is the deal, mate–elation and despair are two sides of the same coin, in equal and opposite proportion. If you want to risk the big win, you’ve got to risk the big low. So instead of trying to deny that, why don’t we stare it in the face?'”

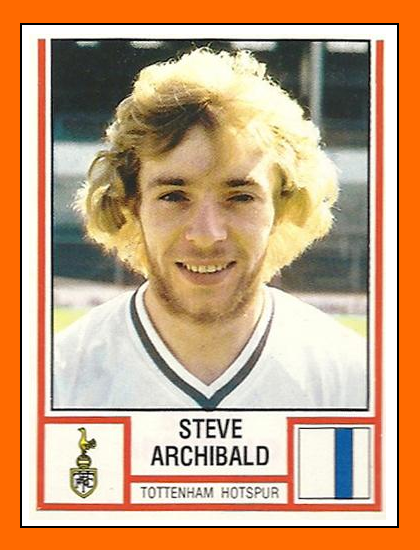

John Syer was the first well-known sports psychologist in the UK. He was a former international volleyball player and coach, who came to prominence from working with the Spurs first team in the early 1980s. His book Team Spirit, one of a string of books he wrote or co-wrote to explain his methods, was published in 1986.

A story I remember well from that book was of his work with the forward Steve Archibald, a talented player who needed a certain amount of anger to play well, but didn’t need it in the rest of his life. Syer helped him deal with this by having him visualise letting a bear(Archibald’s own image) out of a cage before the game, and then returning it to the cage after the game.

I remember the story because I tried a version of this myself in the early 1990s. I had taken a job in a new role that brought me into conflict with some of the engineers in the television company, and the head of department and his deputy proceeded to try to undermine me in every way they could. Nothing was too little trouble for them. Every day–for the better part of a year–was a sea of passive aggression.

By the time I went home each day, having absorbed the best or worst they threw at me, I always felt terrible. Remembering Syer’s story, I found a box and put it in the bottom of my filing cabinet. Before I left for the night, I would go through a ritual of visualising removing their hostility and leaving it in the box, in the office. It worked well enough.

As for Boardman, in that famous Prologue win, where he rode faster than any Tour rider before or since, he caught his ‘minute man’, the rider who left sixty seconds ahead of him, which shouldn’t really happen to professionals in a ride that lasts for eight minutes. His minute man? Luc Leblanc. What goes around, comes around.

Advertisements Like this:Like Loading...