In which I alienate Robert Jordan fans and Harry Potter fans in one swell foop.

In which I alienate Robert Jordan fans and Harry Potter fans in one swell foop.

The other night in our writing group at the Fairlee Public Library I read a passage from my novel-in-progress Firesage. I spent a little time building up the world for my fellows, then read the passage. I explained that the sorcerers who are the main characters live in an academy, and a little bit about the scheming that is tearing it apart. I almost forgot to mention that the main character is pregnant. That wasn’t so important for the passage I read, but it’s most of the basis of the conflict in the novel. I didn’t stop and fill in the background as I went along, because the passage was a flashback to a time before the novel begins, when the main character was “discovered” in a different setting than the one I had just explained.

My main complaint about this book so far, is it seems “thin” or “small,” and I’ve been trying to add something I call “crunchy complexity” to it. Crunchy complexity is a level of vividness so real that not only are the characters real, but the reader can anticipate where their internal struggles come from. In other words, if a particular choice comes up for a character the reader knows his or her dilemma within the moral and ethical rules of that world. A common ethical dilemma is using magic as a weapon, as in The Wheel of Time by Robert Jordan (at least for Aes Sedai), and the Sunrunners in The Dragon Prince by Melanie Rawn. My work-in-progress so far has seemed to lack this level of complexity, where the characters and the readers are in on the customs and mythology of the imagined culture, and the characters are so thick that you can hardly keep track of them. Like real life.

I had a different impression after I read the passage out loud. The book didn’t seem thin or small anymore, it seemed vividly complex, to the point where we explored the world in discussion for as long as I took to read the passage. My colleagues kept asking questions and I kept saying “Well, because in an earlier chapter she sees this oracle who talks to the dead” or “Because in this world women might lose their magical powers after childbirth” or whatever it was. Someone made the comment that if the magical diagrams I suggested were going to be so important to the story, they might need to be illustrated. Totally doable, even though it might be in the page margins or chapter headings. The end result was that I felt the world was complex and vivid enough. I could use the criterion that if a passage from the middle of the book needed that much explanation, it had plenty of crunchy complexity.

Books need crunchy complexity in one way or another. If you read a book that didn’t have it, think of what you would be missing. The real question is how you build it up. Stephen King comes to mind, because I’m reading an especially crunchy book of his, IT, but that complexity is built in a totally different way. As in his novella “The Body,” the story is about a gang of kids in the fifties in Maine, and he does an excellent job of adding the vivid details of what it was like to live in that world. This is clearly not just “write what you know” but “write what you lived” if you’ve read On Writing. It feels real and vivid, especially because of the brand names, street names, pop songs, and celebrities that he mentions. I love King’s use of details in the Pie-Eating Contest segment of “The Body,” particularly when he says a man in a western-style shirt throws up on a Pekinese. It doesn’t really matter what kind of shirt the guy is wearing or what breed of dog it is, but those details cost little and add the vividness that made that sentence real enough to make me laugh for a few minutes. Compare that to the world of The Gunslinger, an exceptionally sparse world with only three real characters, much of which is desert. It still feels real because the psychologically relevant details, particularly for Roland, are all mentioned.

He’s got a pipe, and long hair, and he played the banjo. You can trust him.

He’s got a pipe, and long hair, and he played the banjo. You can trust him.

John Gardner spelled out why vivdness is so important in The Art of Fiction:

We may observe…that if the effect of the dream is to be powerful, the dream must probably be vivid and continuous—vivid because if we are not quite clear about what it is that we’re dreaming, who and where the characters are, what it is that they’re doing or trying to do and why, our emotions and judgments must be confused, dissipated, or blocked… By detail the writer achieves vividness… (pgs. 31-32)

Gardner also notes that lack of vividness is a symptom of amateur writing:

A scene will not be vivid if the writer gives too few details to stir and guide the reader’s imagination; neither will it be vivid if the language the writer uses is abstract instead of concrete. If the writer says “creatures” instead of “snakes,” if in an attempt to impress us with fancy talk he uses Latinate terms like “hostile maneuvers” instead of sharp Anglo-Saxon words like “thrash,” “coil,” “spit,” “hiss,” and “writhe,” if instead of the desert’s sand and rocks he speaks of the snakes’ “inhospitable abode,” the reader will hardly know what picture to conjure up on his mental screen. These two faults, insufficient detail and abstraction…are common—in fact all but universal—in amateur writing. (pg 98)

I see two ways of building up complexity. I don’t think they’re extremes, but please let me know what you think. One way is to mention bloody everything to the point where readers think most of it is irrelevant. This is definitely the approach taken by Robert Jordan and Melanie Rawn, as I mentioned above. If there’s one complaint about The Wheel of Time, it’s “Who cares what these people are wearing!” The rejoinder to that is that it’s incredibly relevant what they’re wearing, because we’re dealing with an ethnically diverse world, and (particularly for the Aes Sedai) they maintain their identity through their clothes. I am of the opinion that most of that detail was actually worth it because it ended up coming out in one way or another important to the story. You won’t see that unless you read the whole story, but beyond that, it’s just a style that is immersive. I wouldn’t normally enjoy that kind of thing, but when Melanie Rawn or Robert Jordan do it, it’s excellent.

Crunchy complexity shouldn’t be employed just to make readers think the world is nifty

A case where I really think most of this complexity is not worth it is in the Harry Potter series. The author (who is that?) only brings in most details when it’s quite relevant to the story, but there’s plenty of atmosphere that is just “hey look at how nifty it would be to live in the Wizarding World!” When Mrs. Weasley was cooking, I often felt like the effects of magic were heavily underestimated, as if the Wizards wanted to pretend to be muggles a lot of the time. It wasn’t crunchy enough that I bought the separation or examples of admixture between the muggle world and Wizaring World, because most of it was just “Hey cool, Wizards don’t need telephones.” That’s okay in a kid’s book, I guess.

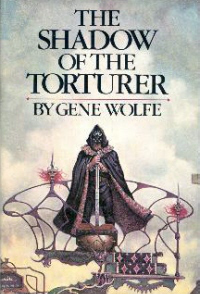

The other approach, the one that I try to take, is to have a richly complex world, and to go into psychological depth with every paragraph. Why is it so significant that this character is left-handed? This requires a thoroughly worked out cosmology and theory of psychology, although that can get out of hand, too. This is, in my opinion though I’d certainly be open to discussion, the approach of Gene Wolfe in The Book of the New Sun. It’s much easier, I find, to add complexity this way, even though it takes a little more background. It looks less bloated, less like irrelevant details are coming in just for the sake of immersive storytelling.

The other approach, the one that I try to take, is to have a richly complex world, and to go into psychological depth with every paragraph. Why is it so significant that this character is left-handed? This requires a thoroughly worked out cosmology and theory of psychology, although that can get out of hand, too. This is, in my opinion though I’d certainly be open to discussion, the approach of Gene Wolfe in The Book of the New Sun. It’s much easier, I find, to add complexity this way, even though it takes a little more background. It looks less bloated, less like irrelevant details are coming in just for the sake of immersive storytelling.

The overall point is vividness. A story has to be vivid, it has to be shown, to be told properly. If not, the readers won’t be sucked in, and they won’t really buy it. I find myself so sucked in to The Wheel of Time that I find myself saying “Wow, even with all these irrelevant details, I can’t put this down.” With Stephen King, the feeling is a little different, more like “I can’t believe how much of this is tell instead of show, but I am still terrified.” Both authors achieve great vividness, and that’s why we love their books. For myself, I think I must have achieved this for the writing that’s been successful, although sometimes it’s hard to tell until I read it out loud for others.

Advertisements