Within Infinite Jest (1996), video telephony is portrayed as both freaky and funny. In his lampoon of this technological innovation, we find David Foster Wallace at his most comical—and most critical.

A videophone prototype at the 1955 San Francisco Electronics Convention. Source: YouTube

The twentieth anniversary of David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest, published in 1996, has come and gone. It remains, however, a seminal novel of the contemporary American literary scene, even notably appearing on TIME’s list of the 100 best English-language novels published since 1923.[1]

Over the course of the novel’s 1,000+ pages, we find ourselves positioned in a society in the near future (from the point of view of the ‘90s) and, even for some of us, in near physical proximity (from the point of view of those of us residing in the United States). The title itself, lifted from the lips of Hamlet holding Yorick’s skull, suggests the seemingly infinite, encyclopedic[2] scope of the novel, which covers a gambit of topics like linguistics, sport and tennis,[3] addiction and rehabilitation, media and film theory, and even Québecois politics—as well also the jest of the novel’s absurd comedy.

Wallace’s humorous and wide-spanning dystopian vision provides an obvious commentary on the social and historical context in which he produced this work. In certain cases, he is able to foresee certain aspects of contemporary American (and global) society that were not necessarily evident at the time. Even if he arrives at an amusingly different conclusion.

Take, for instance, the passage found on pages 144-151.[4]

Its header amounts to a somewhat simple question, despite the twists and tangents that run over a page long and which are part of the downright fun in reading Wallace… if you choose to follow him. The header boils down to the essential question of asking “[w]hy…callers thrilled at the idea of phone-interfacing both aurally and facially…but why…the tumescent demand curve for ‘videophony’ suddenly collapsed … and but so why the abrupt consumer retreat back to good old voice-only telephoning?”

Here, one of Wallace’s many narrators immediately posits, “The answer, in a kind of trivalent nutshell, is: (1) emotional stress, (2) physical vanity, (3) a certain queer kind of self- obliterating logic in the microeconomics of consumer high-tech.”

Reading the passage in the present day, we are immediately confronted with his recognition—back in the ‘90s—of the potential of “videophony” and its homologues that we can find in our everyday lives. We only have to turn on our computers or phones to find Skype, FaceTime, Snapchat, webcams, front-facing selfie cameras… The list goes on.

Nevertheless, the concept of the joining the technological capabilities of transmitting live images and sound together is not a new one. The idea even became a somewhat popular technologic fantasy in the United States and Europe in the second half of the nineteenth century. For one, French author Albert Robida makes reference to the idea in his 1890 science fiction novel Le Vingtième siècle. La Vie électrique (The Twentieth Century: The Electric Life).

On her live stream, Jennifer Kaye Ringley broadcast various parts of her day-to-day life. © Jennifer Kaye Ringley

This technology has concretely existed ever since 1936 when Germany developed the world’s first public video telephone service, the Gegensehn-Fernsprechanlagen. But in the 1990s, leading up to the novel’s publication, there were greater developments on the front of popularizing video telephony. For example, the first commercial webcam, the Quickcam, was launched in 1994. Videoconferencing technologies like 1992’s CU-SeeMe were developing, too. In 1996, Jennifer Kaye Ringley launched the site JenniCam and was the one of the first people to stream her daily life on it.

What makes Wallace’s passage so remarkable then and especially nowadays is his sometimes-grotesque humor in the presentation of the eventual failure of “videophony,” serving to paint the portrait of a society gripped by narcissism and vanity. And all of this almost two decades before the Year of the Selfie, or Twitter’s designation for the year 2014 in a very David Foster Wallace-ian twist.[5]

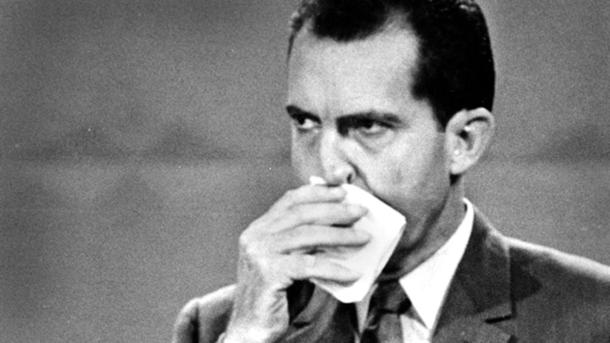

Anxiety grips Infinite Jest’s consumers over how they physically appear in the “facial close-ups” transmitted by the “too crude and narrow-apertured” videophones. Far worse than “just ‘Anchorman’s Bloat,’ that well-known impression of extra weight that video inflicts on the face.” Instead, people’s “phone-faces” appeared “blurred and moist-looking…[with] a shiny pallid indefiniteness that struck them as not just unflattering but somehow evasive, furtive, untrustworthy, unlikable.” In a wink to a well-known anecdote of history that has come to serve as a warning over the power of new technologies, the narrator acknowledges the comparison to Richard Nixon’s 1960 debate appearance against the media-savvy JFK.

Then-Vice President Richard Nixon sweats under the lights and pressure of the 1960 presidential debate with JFK. ©DR

Yet the passage really takes off in the Wallace’s gleeful yet disdainful portrait of consumers’ solutions to cure their “Video-Physiognomic Dysphoria (or VPD).” To serve their narcissistic desires and anxieties, consumers resort not only to “makeup, toupee, surgical prostheses, etc.” but also other grotesque contraptions that the narrator describes in bemused detail. There are even permanent facemasks that were made from “enhanced facial image[s cast] in a form-fitting polybutylene-resin mask.”

To drive his point home, Wallace even sets a sort of punch line at the end of these macabre descriptions of vanity. Consumers invest in “full-body polybutylene and -urethane 2-D cutouts — sort of like the headless muscleman and bathing-beauty cutouts you could stand behind and position your chin on the cardboard neck-stump of for cheap photos at the beach.” Or alternatively, they purchase “video-transmitted image[s] of what was essentially a heavily doctored still-photograph, one of an incredibly fit and attractive and well-turned-out human being, someone who actually resembled you the caller only in such limited respects as like race and limb-number.” [Emphasis mine in both.]

These absurd and absurdly described devices can only lead us to believe that Wallace was a fan of previous dystopian outings like Terry Gilliam’s 1985 Brazil. In this film, Gilliam similarly satirizes the vanity of consumers. One woman, in particular, is obsessed with the grotesque plastic surgery practices of literal face-lifts.

Like in Infinite Jest, appearances are grotesquely rubbery in Terry Gilliam’s Brazil (1985)

In his characteristic way, Wallace plays around with language as a plastic art, stretching and molding his text like the Brazil-ian plastic surgeon. In this passage, he not only stretches sentences to incredible length, a technique employed to great effect elsewhere in the novel too, but also he sculpts the content of the sentences themselves.

Here, above all, Wallace mixes technical (and technological) language that is both grounded in the real world of telecommunications (“fiber-digital grid”, “broadcast/cable”, “video-image-fiber”) and solely in his dystopia. As in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World,[6] neologisms like “Teleputer” (also called “TPs” in the passage) and “videophony” have a decidedly—and most likely purposefully—techie quaintness, calling to mind other terms that have been coined throughout the history of sci-fi and speculative literature.

In the interplay between high and low, technical and non-specialized language and the outright jest of the comparisons of his descriptions, David Foster Wallace reveals the mischievous nature of his critique. And the cherry on the cake: It’s perhaps even more relevant in 2017 than at the time of Infinite Jest’s publication in 1996.

Corey Steinhouse.

[1] The year marker used to exclude one of the novel’s prominent predecessors perceived to be as discouraging a read, namely James Joyce’s revolutionary 1922 novel, Ulysses

[2] Some of the notorious 300+ endnotes even have their own footnotes; others continue for pages on end.

[3] Like the boys in the Enfield Tennis Academy (ETA), Wallace was himself a ranked junior player at one point in his life.

[4] The pagination comes from the first edition, which has been remained the standard in all subsequent American ones.

[5] In Infinite Jest, Wallace’s Organization of North American Nations (ONAN) has adopted “Revenue-Enhancing Subsidized Time,” where brands can sponsor a certain year. In this passage, there is, of course, the most absurd of all of these when most of the novel’s action takes place: the Year of the Year of the Depend Adult Undergarment.

[6] The comparison with that novel goes even further. Like Wallace’s sponsored years, there is the “After Ford” periodization in Brave New World.

Advertisements Share this: