It was fantastic news to hear this week that Sting’s The Last Ship will be touring the UK next year. After a short run on Broadway and a recent version launched in Turku Finland, this production will be especially adopted for a UK audience. Featuring fellow Geordie Jimmy Nail, I am sure it will have a significant impact in Newcastle in particular.

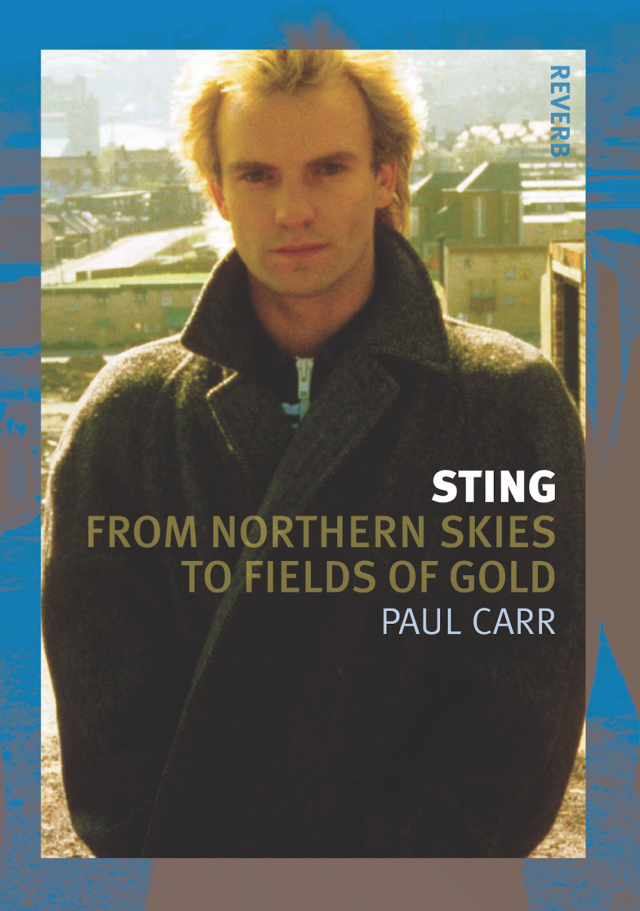

As many readers of this blog will know, my impetus to write my book, From Northern Skies to Fields of Gold, is because it has the same backstory as Sting’s The Last Ship. Coming from Newcastle, and being from a similar social background to Sting, I have, in many ways, also attempted to engage with my own fluctuating relationship with my hometown over the last thirty years, through writing the book. In my mind, after moving to London upon leaving Music College in 1984 and residing outside of the area ever since, Newcastle has become a place of my own idealized construction. I, like Sting, have found myself drifting in and out of my ‘Geordieness’, straddling the complex dividing line between naturally disguising my accent for both practical and class-related reasons, to feeling an intensely tribal, almost jingoistic pride of my homeland, something that has intensified as I have got older. So when Sting released the album The Last Ship a few years ago, after listening to the first few tracks, the music spoke to me profoundly. Many of the songs directly spoke to my own background, including my relationships with family and friends, the various jobs that I undertook after leaving school, social expectations, and my hometown of Blaydon.

As I mention in the book, in the song ‘Dead Mans Boots’ in particular, it was easy for me to not only understand its content as a ‘passive observer’ (where the music has no real emotional resonance), but also for me to inhabit the song. It was easy for me to be what Alan Moore describes as the ‘possessed protagonist’, where I became the person singing the song and at times, having the song sung to me. I first experienced this in Sting’s music when I heard the track ‘Why Should I Cry For You‘ from The Soul Cages in 1991. When I met Sting a couple of years ago, he explained how this feeling some of us feel as part of our Geordie identity is almost impossible to explain in words, but I would argue that he can express these feelings via music – an expression that has frequently used to combat his writers block.

Most importantly, these feelings and emotions are not personal to Sting – they are universal. As Joe Sharky discusses in his excellent book Akenside Syndrome, the simultaneous love and hate of Newcastle is a real phenomena experienced by many people. It is however particularly fueled when one realises the viability of any return is indeed impossible. It is the experience of this phenomena that has fueled my own work on Sting: From Northern Skies to Fields of Gold. Although the book is about Sting, its meta narrative is about this much larger phenomena.

The meaning of the term ‘Geordie’ has been debated over many years, with historians Robert Colls and Bill Lancaster asserting that‘there is no definitive meaning to the name’ These authors provide a number of disputed meanings for the word, such as ‘a name given to coalminers’, ‘a term for the Tyneside dialect’ and ‘people born within three miles of the banks of the river Tyne from South Shields to Hexham’. Being born in Blaydon with the Tyne on my doorstep, I have often used this as a ‘right of passage’ to describe myself as a ‘true Geordie, despite the fact I have lived outside the area for years.

These ambiguities resonate with the depictions of the region by the media, which often describe it as ‘grim’ or ‘spectacular’, ‘amusing’ or ‘threatening’, ‘artistic’ or ‘unqualified’, although adjectives such as ‘grim’, ‘threatening’ and ‘unqualified’ often take the dominant position unfortunately. One need only look one of Sting’s biographers’ depictions of his background to see examples of this narrative:

‘All around lay miles of drab, quarried hills, slag-heaps and allotments’; ‘How many children from a background of backstreet slums and near poverty have made it to the top in any decade this century?’

Even Sting, especially in his early relationship with his hometown, had a tendency to play on this, as I have frequently done myself when romanticing how ‘tough my school days were’ However, placing these statements into context, regions such as Newcastle have to be considered ‘imagined communities’: ‘Who the Geordies are depends on who they imagine themselves to be’, with belonging’ being ‘an act of affiliation not just of birth.

As I have frequently discussed with my wife, the fact that my own recollections of Newcastle are often related to this ‘imagined north’, does not make them any less real. Indeed it could be argued that authors such as Dylan Thomas wrote more profoundly about Wales – when he viewed it from a distance. The same is true of Sting. Having lived outside Newcastle since early 1977, Sting’s perspective on his home town can realistically be nothing but mythical and poetic, but it is this ‘imaginary North’ that continues to exert a gravitational pull on him. This North is refracted through separation, wealth, loss, travel and all that Sting has experienced over the last four decades. It is this North that he and many of us call home.

I can’t wait for The Last Ship to start

Share this: