A belated Happy New Year to you all!

If you read my last post All things Polar, you’ll know that I’m a massive fan of polar exploration. On 28th December, I finally had the opportunity to visit ‘Death in the ice’ at the Royal Maritime Museum, Greenwich, about the lost Franklin expedition.

Led by Sir John Franklin, this voyage set sail in 1845 to explore and chart the final, undiscovered section of the North-West passage in the Arctic – this was believed to link the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans and would be open at certain times of the year, ice-permitting. At 59, Franklin was not a young man, but both he and his second, Captain Francis Crozier, were experienced polar explorers, as were many of the other officers and able seamen who made up the 129 crew aboard HMS Erebus and Terror. According to the Victory Point Note left in a cairn, they spent their first winter at Beechey Island. During September 1846, the ships became stuck in the ice off the coast of King William Island, and were eventually abandoned in April 1848. By then, 24 men including Franklin had died, and the remaining men – led by Crozier and Commander James Fitzjames – were planning to walk for the Back River (and follow the river south towards known trading outposts). Despite Lady Jane Franklin’s indefatigable lobbying for the Navy to raise as many rescue expeditions as possible to search for her husband and his crew by offering handsome rewards, no survivors were ever found – several of these search vessels also became trapped in the ice and needed rescue.

All that was found were various relics (including medals, cutlery, belt buckles, snow goggles, etc.), Inuit eyewitness accounts of meeting groups of exhausted, starving men, and human remains. When and how the crew died remains a mystery, although archaeological research on the found body parts suggest a possible number of causes including tuberculosis, scurvy, lead poisoning, as well as noting that approximately 25% of the bones recovered show damage consistent with cannibalism (bodies being dismantled or prepared for food).

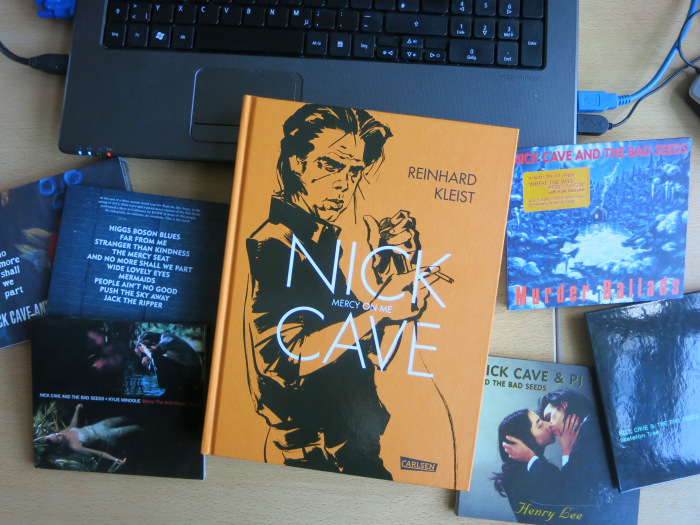

When the wrecks of HMS Erebus and Terror were discovered by Parks Canada’s Underwater Archaeology team (in 2014 and 2016, respectively), I had hoped that there would be an exhibition in the UK to display the new findings so I was very excited when I found out about ‘Death in the ice’ – I’m pleased to say that I wasn’t disappointed. In many ways, the exhibition was exactly how I expected it to be – featuring some of the new artefacts obtained from Erebus, alongside relics from the archives, paintings, drawings, models of the ships, extracts from letters, maps, as well as multi-media installations such as videos of the wreck sites, Arctic landscape and sound effects. It was fascinating to finally look at some of objects I had read about – including the actual Victory Point Note – and I was delighted to see Erebus’s bell; the heart of the ship which marked when the crew rose, worked, ate and slept.

But there were a few welcome surprises too. Two of these were maps; the first was a digital video which began as a blank space, but then as each expedition route was charted (from Martin Frobisher in 1560s to Robert McClure and John Rae in 1850s), the newly-discovered islands, inlets and beaches gradually appeared and were named – this was a very effective way of showing how the North-West Passage was mapped. To contrast, there were examples of three-dimensional Inuit maps of the coastlines – these were carved out of wood and acted as aide-memoires when used alongside the traditional navigational knowledge passed down through the generations; when compared to standard cartography, they were almost perfect representations of the land. In addition, there were audio recordings of the testimonies of Inuit who had seen and communicated with survivors – spoken by their descendants – which were fascinating as I had never heard any of these dialects before.

Another discovery was the animals aboard Erebus: Jacko the monkey who according to an officer’s letters was an annoying pest but could be very amusing, a Newfoundland dog called Neptune who was very popular with the crew, as well as an anonymous cat who caught rats. Unfortunately, animals on difficult polar expeditions tended not to have long, happy lives (including my favourite historical cat, Mrs Chippy from Shackleton’s Endurance expedition) so I suspect their fates were as grim as the rest of the crew’s.

The exhibition also featured haunting photographs of the remarkably well-preserved bodies of the three crew members – John Torrington, John Hartnell, and William Braine – who died during the first winter at Beechey Island and were buried in the permafrost. During the 1980s, their bodies were exhumed, photographed and examined – this process is outlined in Frozen in Time by Dr Owen Beattie and John Geiger (recommended if you’d like to know more about the archaeological research into these bodies and other expedition human remains). At the exhibition, the photos are displayed respectfully behind a curtain and positioned so that it was as if you were looking down at the men lying in their coffins – it was startlingly eerie, but also affecting to look at the faces of men who died so long ago.

Many of the objects displayed were poignant: a single officer’s shoe recovered from the Erebus, a tiny beaded purse found on one of the boats that had been man-hauled away from the trapped ships, a torn message in a tin left by a search party which appears to have been damaged by a polar bear’s bite, two left-handed gloves with small hearts embroidered on the palm which were discovered on Beechey Island (as if left to dry and then forgotten about). I couldn’t quite bring myself to read the full text of the letter written to John Diggle (HMS Terror’s cook) in 1848 by his concerned parents who were worried about him – which was sent with one of the rescue expeditions, only to be returned 11 years later as there ‘having been no means of forwarding it’ – this stamp on the front of the envelope was heartbreaking enough. Sometimes it is easy to get wrapped up in the mysteries of the expedition, forgetting the human side of the tragedy – that these men left behind families and friends who went to their graves without knowing what happened to their loved ones.

The exhibition did not offer a single hypothesis as to what had happened to the crew – it simply presented examples of possible disease,injury and misfortune, which allows the visitor to make up their own mind. This is one of the reasons why the mystery is so compelling – like all good ghost tales, so much remains uncertain so it allows you to project your own ideas onto the story. Through the years, it has provided great inspiration for writers, artists and musicians, although this hardly featured in this exhibition. Ideally, I would have liked more about Franklin’s impact on culture, but I appreciate that this may have widened the focus too far away from the newly-discovered artefacts.

‘Death in the ice’ is now in its final few days (it runs until 7th January – tomorrow), however, if you miss it, I suspect there will be another exhibition in a few years time. There are plenty of secrets waiting to be discovered; further salvage visits to the wrecks are planned, and researchers have requested that the descendants of the crew offer DNA samples so that some of the human remains might be identified. HMS Terror has not yet been explored but the wreck is thought to be in very good condition. As unlikely as it sounds, it is even possible that Crozier’s journal or other important logs or letters may be found on board, although whether they will be legible enough to read is another matter. I am sure that whatever is found will draw large crowds – despite the exhibition opening in July, it was quite crowded when we visited in December, indicating that that there is still plenty of interest in this frozen beard story.

Advertisements Share this: