For six years I tended this rose bush and she was a beauty. I thought of her heard of the summer scents of Houston: roses and jasmine, orange blossoms and water lilies. That was before the floods drowned the flowers, robbed the city of fragrance and left people, their belongings, and their very souls inundated. Later the receding waters will leave another scent, a toxic smell of mold and gas that burns the spirit and the lungs.

For six years I tended this rose bush and she was a beauty. I thought of her heard of the summer scents of Houston: roses and jasmine, orange blossoms and water lilies. That was before the floods drowned the flowers, robbed the city of fragrance and left people, their belongings, and their very souls inundated. Later the receding waters will leave another scent, a toxic smell of mold and gas that burns the spirit and the lungs.

Long ago in a place and at a time I cannot recall, a young woman led me through her flood-damaged home. She grieved for lost photos and her wood floors, now rotting and buckled. My keenest memory was the pungent smell of mildew. It crept from the ruined carpets, sneaked through cracks in the wall. “We can’t live here anymore,” she said. “It’s so hard to breathe.”

The cities and towns of Texas will need resources and time to purify the deluged land and rid it of poisons. Yet the scent of new wood won’t erase the memory of rot. One of these days, though, a flower will lift its head from the ground. A dining room table will be graced with a bouquet of roses, the fragrance filling the air with the scent of a new summer. But not yet.

My heart goes out to the people of Houston. I ache for the flooding they have suffered. Yet here, in Hillsboro, Oregon, I long for rain. I long for water soaking into dead grass. I want the sun hidden, not behind smoke and dust from wildfires, but behind moisture-drenched clouds.

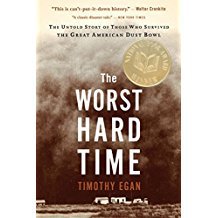

Maybe my desire for rain comes also from entering into Timothy Egan’s rendering of the 1930’s Dust Bowl. Before grassland in the High Plains was plowed into dust, apple trees and wheat scented the air. The car and tractor brought smells of metal and gasoline and fresh dollar bills. The aroma of cigarettes, prostitute perfume, and booze were signs of progress. Then, like the deluge of flood waters, dust storms arrived. The sky blackened, the crops died, and the lungs of children and animals bloated with sediment. Sunshine and no rain, and the dust rolled in, miles and miles of it, years and years of it.

Maybe my desire for rain comes also from entering into Timothy Egan’s rendering of the 1930’s Dust Bowl. Before grassland in the High Plains was plowed into dust, apple trees and wheat scented the air. The car and tractor brought smells of metal and gasoline and fresh dollar bills. The aroma of cigarettes, prostitute perfume, and booze were signs of progress. Then, like the deluge of flood waters, dust storms arrived. The sky blackened, the crops died, and the lungs of children and animals bloated with sediment. Sunshine and no rain, and the dust rolled in, miles and miles of it, years and years of it.

Dust. I grew up in Pendleton, Oregon, land of wheat fields. My mother believed in living positively. “Put your best foot forward.” But she hated, with a passion, the dust storms that swept through the town. “Close the windows,” she called out. Dust rolled up to the house and left its gritty remains on the sill outside, table tops inside, under the door, through the windows we could not close in time. Dust had its own smell—a static, mealy buzz in the nostrils. A nuisance for some, a hindrance to breathing for others.

Hurricane Harvey and the Dust Bowl threw nature off balance and left us with extremes—the worst storm and the worst hard time. Too much. I wonder what a world of just enough would resemble? A different way for us to live: enough rain to make the flowers grow; enough dust to make sunset spectacular.

Share this: