Distant Thunder is, like so many of the best of Satyajit Ray, a sensitive look at a singular relationship set amidst changing circumstances. I think that Ray really liked the idea of the outsider (see Utpal Dutt in The Stranger, or Madhabi Mukherjee in The Big City for examples of two different, learned (or maybe we should just say “non-ignorant”) people functioning outside of the societal norms upon which they intrude). He’s got several of those characters in Distant Thunder, a really touching film about a famine in an Indian village in the early-1940s.

One of those is Gangacharan (Soumitra Chatterjee), a teacher and priest who angles for advantages, yet is not an unsympathetic character. His relationship with his wife Ananga (Bobita) really reminds of the husband-wife dynamic in The Big City, yet here the tension comes more from without than within. Gangacharan strikes me as a fairly typical Ray protagonist. He’s smart, but needs to learn about life; he has kindness in his heart, but struggles with pride.

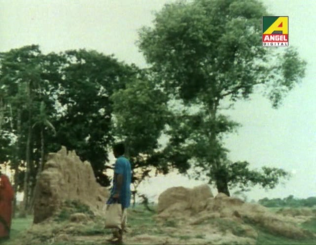

The title refers to the war that’s never seen but frequently heard, and which, importantly, is the cause of the food shortage. Ray often lenses the landscape in wide frames-

These are gorgeous but also add to the sense of isolation. That thunder is distant, which is good in one sense (the violence of war isn’t imminent), but also bad (the village is cut off from food access).

I imagine that Ray is often thought of as a social filmmaker first, and a visual filmmaker second. I remember hearing an interview with one of his actors years ago (I can’t remember who) and she said that his films often had so little money behind them that they’d get one take and be forced to move on, but that Ray came so prepared that the scenes still felt complete and organic.

There are a lot of sequences in Distant Thunder that give credence to this preparation, and that also paint Ray as a master visualist. One of the best is between Chutki (Sandhya Roy) and Jadu (Noni Ganguly). Jadu is the ultimate outsider in the film. He lurks on the outskirts of the village, hiding in ruins, keeping his scarred face from view.

As the famine escalates Chutki encounters Jadu while walking. Ray shoots this sequence so expressively. It’s full of longing on many fronts. Chutki wants rice. Jadu wants to sleep with Chutki. It’s a scene that another director might play as eerier, or even violent. For Ray it’s sad.

The sequence starts in this wide with a low horizon. The camera pushes in as Jadu approaches Chutki:

A transition shot of a lizard later-

-Ray cuts to this wide of the ruins. Jadu walks into them. The camera pulls back to reveal Chutki in the foreground. Then she exits frame left and we push in to the empty structure:

Jadu emerges, and in the same long take we now track left to right with him as he finds Chutki, who has turned his back on him and walked away (but not too far away):

He approaches her from behind and holds the rice out over her shoulder. She knocks it away. I love this moment. There’s so much decision in her face. Her openness to camera feels blunt but it works. She’s doing this for the rice but slapping it from his hand is so angry and instinctive.

I’ve skipped a few shots, but the scene ends beautifully and sadly. Ray tracks left to right with Chutki as she walks away from Jadu again. The ruins are in the foreground:

We cut to a tight CU of Jadu. The camera pushes in on him a little bit:

And then to his POV. A tragically wide shot of Chutki, nearly blending in despite her red sari:

The scene is so haunting. It’s mostly wordless. Ray’s camera moves often and, though it does in fact move for Jadu (see the second-to-last shot above where it pushes into him) it’s mostly motivated by Chutki and her literal movement or her absence. The wide frames, the characters pushed to the fringe – there’s nothing romantic about this. It’s a desperate scene.

It’s amazing how Ray is able to make Jadu sympathetic. Though he carries hints of violence with him he’s never outwardly violent. Still, he’s far from innocent. He uses the rice as a way to manipulate Chutki. Of course, it’s partially the performance and makeup. It’s also that other characters in the film are much less sympathetic. But it’s also Ray’s desire to look at how desperate situations make people more desperate.

What’s Up, Doc?

Peter Bogdanovich’s What’s Up, Doc? owes a big debt to Bringing Up Baby and to Blake Edwards. It’s a funny film, buoyed by some slapstick set pieces (the wrong room motel hallway wide shots are great), and Ryan O’Neal and Barbra Streisand have good chemistry.

Maybe the best part of What’s Up, Doc? is simply reveling in the return of the screwball. Bogdanovich makes no bones about his references (can O’Neal channel Cary Grant any more?) and, true to the subgenre, just tries to up the ante from scene to scene.

The definite highlight is a plate glass gag. Who did the first one of these? It has a Buster Keaton feel to it, but I can’t think of a Keaton film that uses it. The packed cars zipping down the street reminds of Edwards’ Pink Panther films. The gag is so great because of Bogdanovich’s constant return to the extras – the guy on the ladder and the characters moving the plate glass. Their choreography is hilarious, and the conclusion of the gag is totally satisfying.

Streisand’s really good in this. I had no idea she had already won an Oscar by 1972. There’s little subtlety in her Judy Maxwell, but there doesn’t really need to be. This is a film about timing, both directorially and actorly timing, and everyone pulls it off. It’s harder timing than it looks. To get people in a long shot of a hallway to open some doors at just the right time is one thing. To play with foreground and background, body language and reactions, all in one frame (as Bogdanovich does really well in the fire/trashed hotel room scene) is another entirely.

Advertisements Share this: