Today, I have a treat for you my friends. We are going to look at the effect Victorian economy had on juvenile offenders. My aim was to try and establish a link between economic background and criminal/recidivist tendencies, and boy, did I find a way to do it! Brace yourselves!

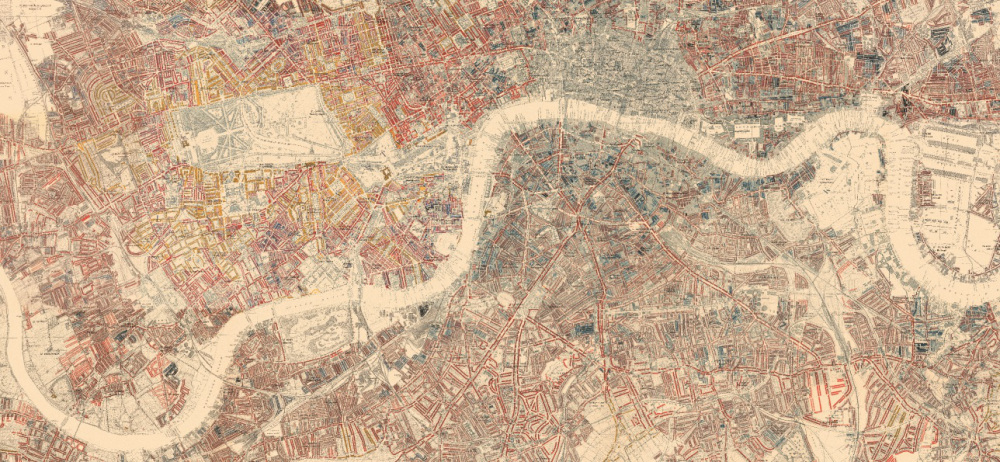

‘Charles Booth’s London’ LSE Library Online. 2016

‘Charles Booth’s London’ LSE Library Online. 2016

This interactive, fully searchable, map has been constructed by the wonderful folks at London School of Economics. The data is taken from Charles Booth’s meticulous notes in his Inquiry Into Life and Labour in London (1886-1903). I would love to go into fine detail about who, where and how I matched juvenile criminals to their economic situation, but, unfortunately, space is at a premium. Suffice it to say that out of 20 convicted, juvenile pickpockets, 18 were born/raised in impoverished areas of London, classified by Booth as either ‘lowest class. Vicious, semi-criminal’ or ‘Very poor, casual. Chronic want’ (LSE Online).

A perfect literary representation is found in Charles Dickens’ 1838 classic, Oliver Twist, when ‘The Artful Dodger’ leads Oliver:

‘from the Angel into St.John’s Road; […] down the small street which terminates at

Sadler’s Wells Theatre; through Exmouth Street and Coppice Row; down the little court by the side of the workhouse; across the classic ground which once bore the name of Hockley-in-the-Hole; thence into Little Saffron Hill; and so into Saffron Hill the Great.’ (Dickens, 1838, p)

Tracking the boys’ journey on Booth’s poverty map is a relative descent into economic hell; the status of the roads they take slowly declines, until they meet Fagin, firmly situated within the ‘Vicious, semi-criminal’ Saffron Hill.

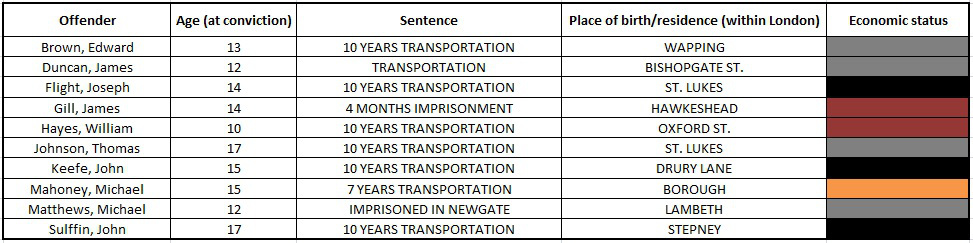

Taking Dickens’ representations of London, I thought I would run a little experiment of my own, utilising the amazing resources provided by the folks at the Digital Panopticon. This hugely extensive collation of crime and criminals provides, at the very least, a starting point for in-depth research into historical crime, between 1780 and 1925. I isolated a specific data-set, focussing on juvenile pickpockets, under the age of 18 at the time of their sentencing. Thanks to the incredibly detailed digital  panopticon profiles, I was able to compare each offender’s place of birth/residence to exact locations on the Booth map and create an economic profile for each juvenile offender. Below is my own chart of the 10 offenders and their corresponding economic classifications.

panopticon profiles, I was able to compare each offender’s place of birth/residence to exact locations on the Booth map and create an economic profile for each juvenile offender. Below is my own chart of the 10 offenders and their corresponding economic classifications.

I referred in an earlier post to social, or class, institutionalisation, and the idea that a person’s situation may make criminal activity the only available method of survival. I appreciate that far more in-depth research would be needed to evidence an assumption such as that. Even at a cursory glance, however, this limited sample shows, that it is, at least, plausible for a person’s criminal tendencies to be heavily influenced by the constraints, or freedoms, of their surroundings.

**I am aware that a sample of 10 subjects is limited, the idea is to indicate a larger trend that begins to appear**

Bibliography

Booth, Charles. Life and Labour in London. 1886-1903. London: Hutchinson, 1969.

‘Charles Booth’s London.’ London School of Economics Library Online. 2016. Web. Accessed 07 December 2017. <https://booth.lse.ac.uk/map/14/-0.1174/51.5064/100/0>

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. 1838. Hertfordshire: Wordsworth, 1992

Parsons, Chris and Amy Oliver. ‘Fagin’s Children’ Daily Mail Online. 2012. Web. Accessed 07 December 2017. <http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2165262/Rogues-gallery-Fagins-children-Mugshots-Victorian-criminals-shows-thieves-young-11-jailed-stealing-clothes-cash-metal.html>

‘Edward Brown’ Digital Panopticon. 2017. Web. Accessed 07 December 2017. <https://www.digitalpanopticon.org/life?id=obpdef2-1683-18430508>

‘James Duncan’ Digital Panopticon. 2017. Web. Accessed 07 December 2017. <https://www.digitalpanopticon.org/life?id=obpdef1-2414-18430821>

‘James Gill’ Digital Panopticon. 2017. Web. Accessed 07 December 2017. <https://www.digitalpanopticon.org/life?id=obpdef3-872-18450407>

‘John Keefe’ Digital Panopticon. 2017. Web. Accessed 07 December 2017. <https://www.digitalpanopticon.org/life?id=obpdef1-1505-18480612>

‘John Sulffin’ Digital Panopticon. 2017. Web. Accessed 07 December 2017. <https://www.digitalpanopticon.org/life?id=obpdef1-1429-18470614>

‘Joseph Flight’ Digital Panopticon. 2017. Web. Accessed 07 December 2017. <https://www.digitalpanopticon.org/life?id=obpdef1-1830-18450915>

‘Michael Mahoney’ Digital Panopticon. 2017. Web. Accessed 07 December 2017. <https://www.digitalpanopticon.org/life?id=obpdef1-1770-18470816>

‘Michael Matthews’ Digital Panopticon. 2017. Web. Accessed 07 December 2017. <https://www.digitalpanopticon.org/life?id=obpdef2-2997-18421024>

‘Thomas Johnson’ Digital Panopticon. 2017. Web. Accessed 07 December 2017. <https://www.digitalpanopticon.org/life?id=obpdef3-1525-18470614>

‘William Hayes’ Digital Panopticon. 2017. Web. Accessed 07 December 2017. <https://www.digitalpanopticon.org/life?id=obpdef1-3070-18421024>

Advertisements Share this: