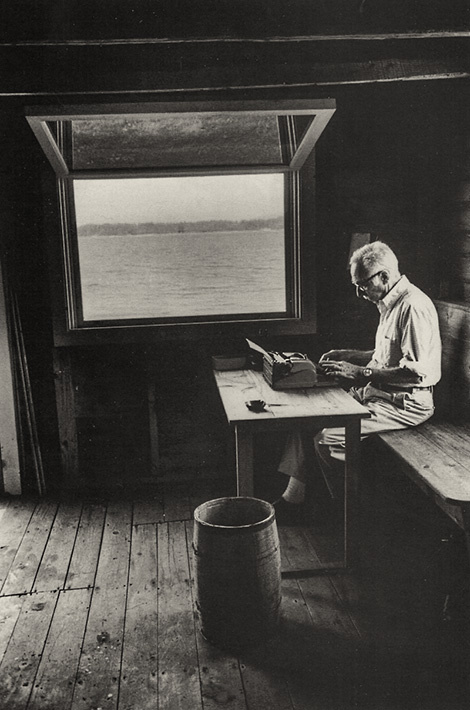

“Always be on the lookout for the presence of wonder,” wrote E.B. White and, when I read this simple sentence, I felt a kindredness with the author. YES! I thought, Exactly right.

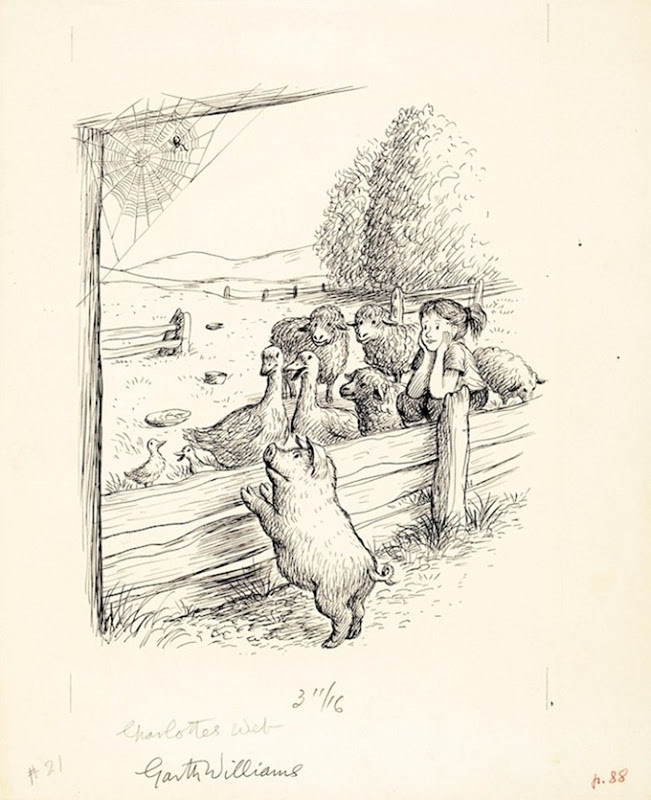

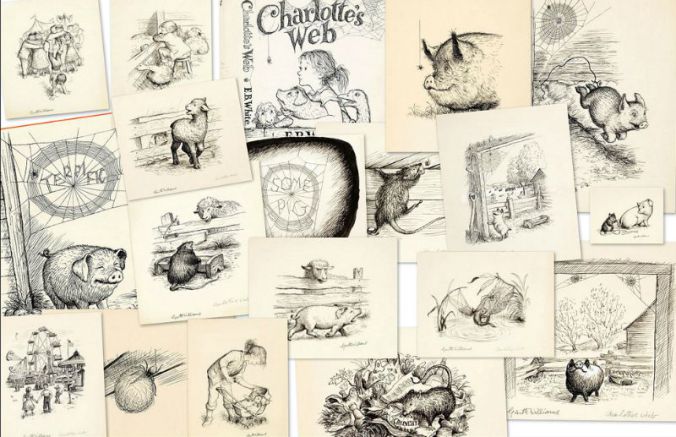

I first encountered E.B. White’s writing when I was an elementary school student and checked out Charlotte’s Web from our school library. Along with introducing me to the world of animals on farms, he was also the one who first shed light on death and dying, getting me to care so much about a spider that I actually mourned her fictional death because it felt as if a real friend had died. For a long time, every spider was “Charlotte.”

What E.B. White did was open my eyes: to not only farm life but to revealing the moods of seasons through vivid descriptions that made me feel what he was writing. Here are two examples:

“The Early summer days on a farm are the happiest and fairest days of the year. Lilacs bloom and make the air sweet, and then fade. Apple blossoms come with the lilacs and the bees visit around among the apple trees. The days glow warm and soft. School ends, and children have time to play and to fish for trouts in the brook. Avery often brought a trout home in his pocket warm and stiff and ready to be fried.”

As someone who went to his grandparents’ farm for a few weeks each summer, it brought to mind their farm. I can recall the bees being around the apple trees and how, after an apple had ripened and then fallen to the ground, it would become soft and my cousins and I had to be careful when we ran past the apple trees or else we might step on one and be stung by the bees that were inside its mushy flesh.

Contrast White’s portrayal of early summer to the end of it:

“The crickets sang in the grasses. They sang the song of summer’s ending, a sad monotonous song. ‘Summer is over and gone, over and gone, over and gone. Summer is dying, dying.’ A little maple tree heard the cricket songs and turned bright red with anxiety.”

In his descriptions, White made me feel the joy and the sadness that came with the beginning and ending of the summer season, a feeling any child knows. Summer always meant freedom. As a small and quiet boy, I preferred books and brooks to crowds and school. School, to me, felt more like a prison where we were made to learn facts that the teacher was telling us were important and that we needed to know. When I read books or explored on my own, I learned the ones that made me think and see the world differently. They expanded my sense of curiosity and fed my desire for learning in a way that I never picked up in school.

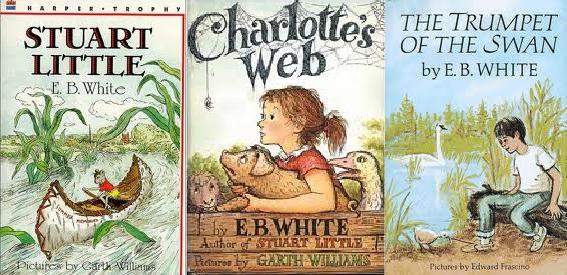

I must have read Charlotte’s Web a dozen times, as well as Stuart Little. Never did I question how the Little family had a mouse for a son, I just envied them. Both books made me love animals in the way that the author so clearly did. His love of words and animals came through in his books.

Years later, when I read the book The Story of Charlotte’s Web by Michael Sims, it did not surprise me that the germ for the creation of White’s book sprang from his noticing a spider spinning a web in the barn of his Maine farm. Because there was early morning dew on the web, the author’s attention was drawn to the elaborate loops and whorls that shined. The web had been transformed from something ordinary and overlooked to something wonderful. From this simple noticing came the miraculous tale of the passage of time, of mortality and of the meaning of true friendship.

When White was asked by his editor why he wrote the book, he explained not only about his love for animals, which was a problem on a farm where the livestock are often killed for meat, he also explained why he would make a spider a main character.

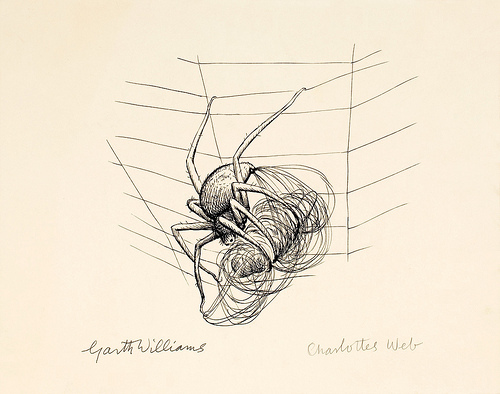

“As for Charlotte, I had never paid attention to spiders until a few years ago. Once you begin watching spiders, you haven’t time for much else – the world is really loaded with them. I do not find them repulsive or revolting, any more than I find anything in nature repulsive or revolting, and I think it is too bad that children are often corrupted by their elders in this hate campaign. Spiders are skillful, amusing and useful. and only in rare instances has anybody ever come to grief because of a spider.

One cold October evening I was lucky enough to see Aranea Cavatica spin her egg sac and deposit her eggs. (I did not know her name at the time, but I admired her, and later Mr. Willis J. Gertsch of the American Museum of Natural History told me her name.) When I saw that she was fixing to become a mother, I got a stepladder and an extension light and had an excellent view of the whole business. A few days later, when it was time to return to New York, not wishing to part with my spider, I took a razor blade, cut the sac adrift from the underside of the shed roof, put spider and sac in a candy box, and carried them to town. I tossed the box on my dresser. Some weeks later I was surprised and pleased to find that Charlotte’s daughters were emerging from the air holes in the cover of the box. They strung tiny lines from my comb to my brush, from my brush to my mirror, and from my mirror to my nail scissors. They were very busy and almost invisible, they were so small. We all lived together happily for a couple of weeks, and then somebody whose duty it was to dust my dresser balked, and I broke up the show.

At the present time, three of Charlotte’s granddaughters are trapping at the foot of the stairs in my barn cellar, where the morning light, coming through the east window, illuminates their embroidery and makes it seem even more wonderful than it is.”

I cannot imagine the world without the book Charlotte’s Web in it nor can I imagine my own childhood without having read that classic of literature. Because of it, White made me pay attention to spiders, to see the magnificence of the glorious architecture and design of their elaborate webs. Another of my favorite authors, Eudora Welty, wrote in The New York Times, “As a piece of work it is just about perfect, and just about magical in the way it is done.” She is spot on with her assessment. The novel is near perfect and it is magical in a way that showing a child nature and the connection we have to it.

Recently I have re-encountered this when I read Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Gathering Moss. It’s astounding how she can write about a subject such as moss, which most of us barely notice, and make it into a work that’s beautiful and profound in so many ways. In one passage she writes:

“Traditional knowledge is rooted in intimacy with a local landscape where the land itself is the teacher. Plant knowledge comes from watching what the animals eat, how Bear harvests lilies and how Squirrel taps maple tree. Plant knowledge comes from the plants themselves. To the attentive observer, plants reveal their gifts.”

That is what E.B. White did. From his observations, he discovered both the reality and the beauty of nature: by humanizing their personalities but leaving them in their predatory natures and their messiness. One of my favorite lines from Charlotte’s Web is,”Life is always a rich and steady time when you are waiting for something to happen or to hatch.” That line reiterates White’s statement that we should always be on the lookout for the presence of wonder because life, nature, will always reward those who are attentive to it.

To open their eyes to pay attention and look for the “presence of wonder,” is one of the reasons why I have read Charlotte’s Web to both of my sons. It is amazing to read it aloud and watch how they reacted to parts of the story, some of them being the same sections that I reacted to as a child. I love how this book caused them both to ask questions and to reflect on human’s relationship to animals and to nature. It’s important that they, too, meditate on mortality, especially as one of our dog’s is older and is approaching that time in her life.

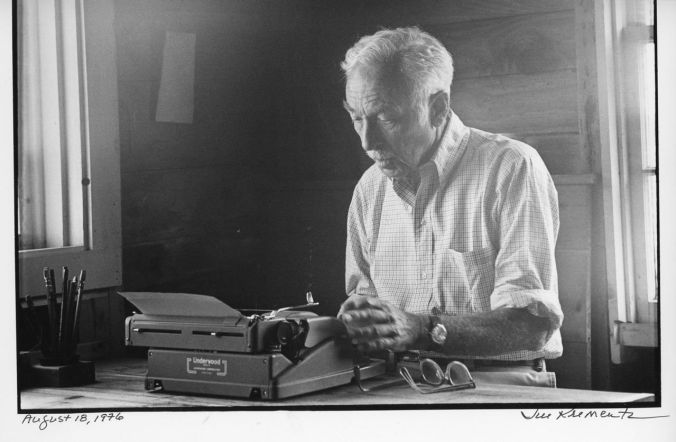

E. B. White is a wonderful writer who’s loves of language and animals transcends the pages of his book and fills the reader with enthusiasms for both. It’s also amazing to me that I am almost the age that White was when he began writing Charlotte’s Web back in the 1950’s. It’s heartbreaking to think that the last years of his life were spent with his suffering from Alzheimer’s. His son Joe would read aloud to his father from his father’s books. When he read to him from Charlotte’s Web, White asked, “Who wrote that?”

“You did, Dad.” He would watch as his father thought about this for a moment before finally saying, “Not bad.”

Not bad, indeed.

E.B. White once said, ” “All that I hope to say in books, all that I ever hope to say, is that I love the world.” That love definitely shines through and allows us to “be on the lookout for the presence of wonder” that he first showed us. What richer gift is there than that?