This weekend, the fantastic Architecture Fringe festival ran a series of events in Abriachan, exploring the histories and possible futures of huts and bothies in Scotland. Among an array of stories, songs and discussions (and treehouses and ceilidh dancing!), we heard from writer, broadcaster and PhD researcher Lesley Riddoch about the comparative histories of huts and land use in Scotland and Norway. In Norway, it’s normal for families to have a small wooden hut somewhere near trees, water and/or mountains for weekend and holiday accommodation – in Scotland, despite comparable population size and no shortage of trees, water and mountains, it is almost unheard of. Reading about the Broons’ but-and-ben is the closest most of us get to the hut life (though we also heard about many big plans to change this… watch this space.)

Huts in a nutshell – spotted at Abriachan Forest School

One of the historical reasons Lesley cited for this was the change in how most people in Scotland lived and worked in the late 18th and early 19th centuries – lowland Scotland underwent an unusually quick and intense process of industrialisation, with people shifting to new urban landscapes and ways of life. And because the vast majority of people were tenants, rather than homeowners, Scottish families lacked the tangible link back to rural land that many people in Scandinavian countries maintained. This, of course, came on top of the forcible and often violent shifting of people which cleared the Highlands into huge swathes of vacant land.

But people held onto the idea of connecting to the world through walking. Over the weekend, my thoughts kept coming back to the many ways in which the people who lived in Victorian Dundee – a city famous for its closely packed mills, thick cloud of smoke and air dusted with jute fibre – made little escapes from the city in body and mind.

As well as being fiercely protective of green spaces in the city, (the 1860 Right of Way campaign to prevent Lord Dudhope turning the Law into a quarry is a great story for another time…) many Dundonian workers looked forward to escaping the mills and factories for hills and glens during holidays or weekends. Like most Scottish cities, 19th century Dundee had a Trades Fortnight when factories would close for a holiday, in late July and early August. This was a welcome and necessary break from long, hard manual labour, and for many, escaping the city was their first priority if at all possible.

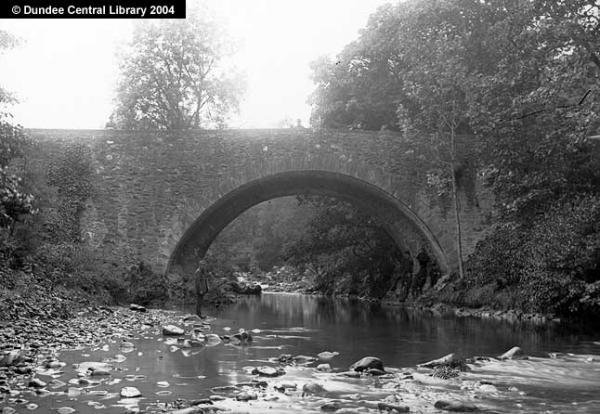

Cortachy Bridge in Angus, photographed by jute mill supervisor Alexander Wilson (no relation!) on a trip out of the city c.1900. ©Dundee Central Libraries: Photopolis Collection.

Adam Wilson, who wrote as The Factory Muse, became a popular voice in Dundee in the 1870s and 1880s. His poetry, which was often directly addressed to his fellow workers, celebrates time spent in nature as a remedy for industrial life. For example, his song “Fareweel tae the Factory,” (published in his 1906 collection Flowers of Fancy), set to the tune of Lochaber No More:

Fareweel tae the factory, fareweel tae the mill;

I’m off for a spell to the glen and the hill,

Whaur the rough thistle waves, and the eagle aye free

Enjoys his love haunts ‘mang the mountains sae hie.

Fareweel tae the mill wi’ its bustle and din,

When spinnin’ life oot we maun spin the life in;

Yet the health-giving breeze ‘mang the heather and broon

Will bring back again to my pale face its bloom.

Fareweel tae the mill while the simmer’s bricht beam

Lichts up the mild beauties of mountain and stream;

My heart will enjoy a sweet lichtsome thrill

That ne’er can be felt in the factory or mill.

Alang wi’ the blackie methinks now I hear

The siskin and mavis in melody clear,

Wi’ yorlin and lintie a’ singin’ their fill,

Awa’ frae the whir o’ the factory and mill.

Laigh doon in yon glen I can dimly descry

A cot wi’ its reek curlin’ up to the sky,

‘Tis there I would dwell until I was laid still

In a quiet place awa’ frae the factory and mill.

Oh, heart healin’ nature, wi’ lavish hand gi’e

The sweets o’ your grand’ur to bodies like me,

Wha seek you when weary, wha bend to your will,

An sair need relief frae the factory and mill.

Regular readers may recall that the tunes poets picked were rarely random. “Lochaber No More,” originally a bagpipe lament with Jacobite connotations, had words put to it by Allan Ramsay in 1724. His song was told by a Highlander, forced to leave his home and his love to go to war:

These tears that I shed they are a’ for my dear,

And no for the dangers attending on wear,

Though borne on rough seas to a far bloody shore,

Maybe to return to Lochaber no more.

In 1883, when the Factory Muse was working and writing in Dundee, the title Lochaber No More was also given to a painting by John Watson Nicol. It depicts a couple whose clothes and few possessions mark them as poor Highlanders, despondent, on a boat sailing into the grey unknown. They have been driven away by the Highland Clearances. (Alistair Davidson here tells us more about Lochaber No More, and its modern life in Letter to America.)

I don’t know if Adam Wilson ever saw, or heard of, Nicol’s painting (he may have composed his song before it was painted – his book was published in 1906, but contains poems written up to thirty years previously.) But a tune which already carried the meaning of leaving and laments is an interesting choice for a song which is a celebration of leaving the mill. Adam’s father Alexander, a handloom weaver from Alyth, was also a poet. Like his son, he wrote under a pseudonym – Alexander Wilson was known as the Mountain Muse. Perhaps Adam felt his own sense of displacement, as the first generation of the family to have to turn to the industrial city for a living.

Reekie Linn, Glenisla – one of the glens Dundee factory workers would have enjoyed an escape to.

Of course, there is a centuries-old tradition of poetry describing the beauty of wild mountains or pastoral landscapes, and it may seem an obvious topic for any aspiring poet. But the meaning of poetry changes hugely depending on who is writing or singing it, and the context it is heard in. When we think about Scottish landscapes in the 19th century, we often think of the Monarch of the Glen – by then a place (artificially) empty of people, to be looked at rather than lived in and walked through; where animals exist for sport rather than as their own entities. Poets like Wilson and his peers, now mostly forgotten by literary history, repopulated the mountains and glens in their imaginations, and in person when they got the chance. Their writing and singing reasserted the right of the working people of Scotland to be in places other than their workplace – often subtly, quietly spreading the idea that access to land and time away from work are vital human rights.

Next Monday, 24 July, is the first day of the 2017 Dundee Fortnight (the Monday is still a public holiday in Dundee). This seems like a good day to go to a hill, a mountain, a green space, a river, and begin to feel at home there. A good day to take back our places.

Advertisements Share this: