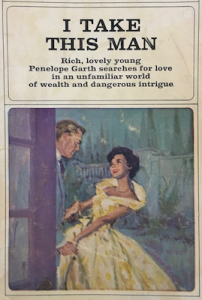

Penelope Sherrod’s mother needs life-saving surgery, and the only way to afford it is for “Penny” to marry wealthy Donald Garth and turn her back on the scoundrel she really loves, Dick Wentworth.

Penelope Sherrod’s mother needs life-saving surgery, and the only way to afford it is for “Penny” to marry wealthy Donald Garth and turn her back on the scoundrel she really loves, Dick Wentworth.

In one eventful day, Dick suggests an affair, Penny realizes she doesn’t love him after all, and she marries Don, but not before he has heard enough to know that his bride only wants to marry him for her mother’s sake. Don agrees to the arrangement, the two are married, and “Marmee” goes off to the hospital with this wedding wish for her daughter:

“I won’t say I want your happiness. You know that. I will just say–God grant that you will be a good and true wife.”

“I won’t say I want your happiness?!!” I’m sorry, but my daughter is getting married next summer, and there’s no way I could send her off with that pious comment! In fact, the whole set-up is fishy.

How is it that the Sherrods are too poor to pay medical bills? And if Marmee is so dear, her condition so tenuous that it requires marital sacrifice, why is it that Penny never visits her mother in the nearby hospital? Instead, she relies on the reports of nurse Nora and brother Terrance, and she seems to know precious little about the plans for Marmee’s recovery.

[Doctor:] “I’m going to have another empty hospital bed today.”

“Mother!” Penny said with a squeal of delight.

“As soon as you have dressed you can go in to see her and say good-by before she leaves for the airport, if you like.”

“Marmee isn’t going alone, is she?” Penny asked anxiously.

Despite its contrived premise, I Take This Man has an interesting plot, and the twist of both Kitty Owens and Geoff Jarvis turning out to be special agents is a nice side story. I also enjoy the little bits of romance flickering between Don and Penny.

But then comes this:

So on a summer night in June, Penny grew up and learned the secret of a woman’s wisdom.

No. A thousand times, no.

That line is too cheesy, too artificial for even the worst teeny-bopper novelette. Thank heaven, Emilie Loring didn’t write it.

I Take This Man was the third of four novels copyrighted by Little, Brown after Emilie Loring’s death. It was based on a 1918 serial novel, “Garth the Gunmaker.”

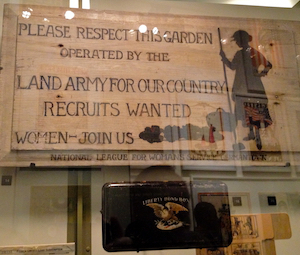

World War I Museum, Kansas City

World War I Museum, Kansas City

Remember what was happening at the time. It was World War I, and Emilie Loring’s sons were both in service, Robert at Camp Dix and Selden at the front-of-fronts in France. Instead of airplanes, “Garth the Gunmaker’s” manufacturing plant made weapons. The original story had the same cast of characters as the later novel, including Dick Wentworth, whose name foreshadowed his fallen graces.

I would love to read “Garth the Gunmaker” all over again, but I made the serious error of not making a complete copy when I had access. “I have the reference information; I can find the original later,” I thought.

Ha!

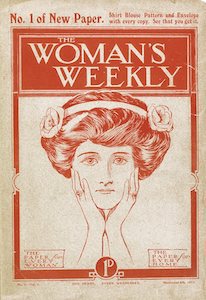

UK magazine

UK magazine  Australian magazine

Australian magazine

“Garth the Gunmaker” began in the July 27, 1918 issue of Woman’s Weekly and continued weekly through September 21st. This was the new, Chicago-based magazine, not to be confused with the UK or Australian titles.

A high-class weekly magazine of national scope

Never before in this country has a serious attempt been made to establish a high-class weekly magazine of national scope devoted exclusively to matters of interest to women.

“Weekly” was important.

From one month to the next is too long a period to retain the plot of a story, interest in an argument, or to wait for the details of a news event… There may have been a time when timely information on all topics, including alert discussion of current events, was of no importance to the women of America, but surely that time has passed. Without in any way lessening their devotion to home, they are all taking a keen interest in the political, social and economic questions which were never before so vital to the general welfare or so much influenced by popular opinion.

This interest Woman’s Weekly will endeavor to serve, at the same time giving attention to those matters of home duty which must always remain first in importance to the average woman.

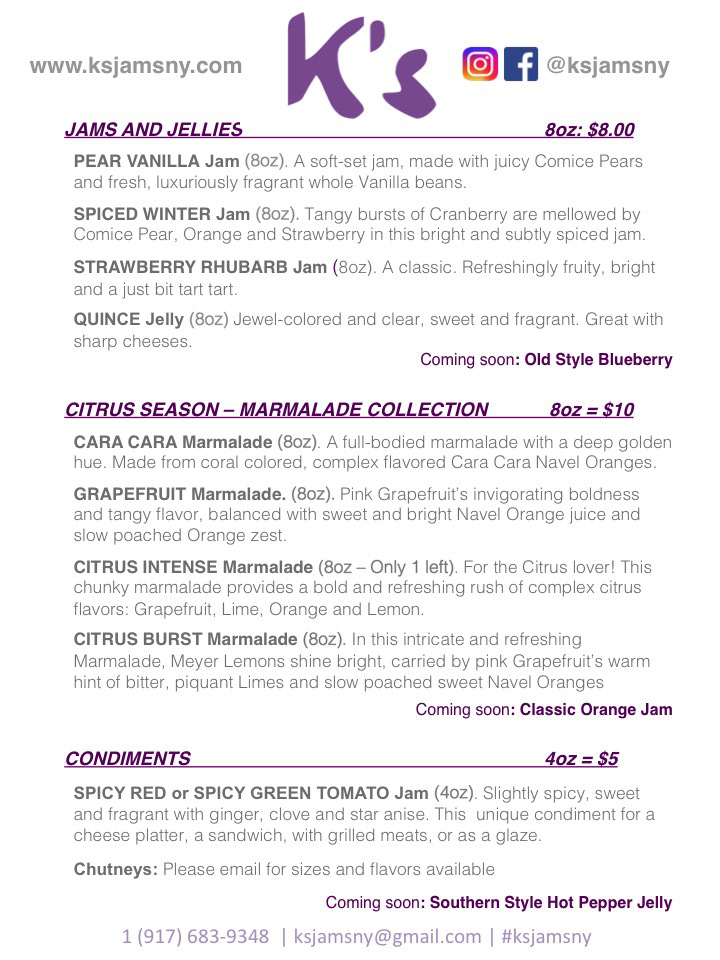

Ad in Printers’ Ink

Advertisers rushed to reach the nearly all-woman audience with everything for the home, from perfumes to cleansers to bandages. You probably can’t make it out in this thumbnail, but I’m amused by the many uses there were for “adhesive plaster tape,” the apparent precursor to band-aids and duct tape: mends lawn hose, umbrellas, broken handles, leaky pipes, and rubber articles of any sort; makes firm grips for golf clubs and tennis racquets; mends cloth; insulates electric wires; and seals fruit jars. No wonder they recommended buying 5-yard spools!

When the first installment of “Garth the Gunmaker” was distributed in July, 1918, circulation was 95,000. By the story’s conclusion in late September, the magazine had a weekly circulation of 103,000 and more than twice that the next summer–with no internet to help it along!

Well, that’s great. There should be lots of copies in small-town libraries and twentieth-century magazine collections.

Well, that’s great. There should be lots of copies in small-town libraries and twentieth-century magazine collections.

But no.

Somehow, Woman’s Weekly escaped the astute eye of the collector, and libraries seem never to have carried them. Two libraries list holdings on WorldCat, and they are minimal. If you have copies, hang onto them–or call me. I have my antennae out, looking for full issues. Until then, I still have notes I took from the original.

I Take This Man ends with Don giving Penny’s room key back to her:

He held it out. “Want it?”

The color deepened in her face. “It belongs to you,” she said, and the words were a promise.

“Garth the Gunmaker” ends:

“Pardon! I remember now that you don’t like to have anyone near your arm when you’re driving.”

“Oh, I don’t!” he gave a jubilant laugh as he slowed the car to a smooth, gliding pace, and drew her closer. “Mrs. Garth, observe this excellent imitation of a one-armed man at the wheel.”

It’s less intense, but, as Emilie would say, “it gets there.”

Share this: