by Ryan Desaulniers and Mark Mitchell

This article contains SPOILERS. If you haven’t read the issue yet, proceed at your own risk!

Ryan D: In the premiere issue of this series, Mr. Akio uses the image of the ouroboros as the symbol for his Project Utopia during his pitch to General West. While this motif appears without much fanfare, it hasn’t been until issue four of Generation Gone that the significance of the serpent eating its own tail begins to fulfill its own inherent meanings. Originally seen as iconography from an ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead, the ouroboros survived through medieval mysticism until finding its home in Renaissance alchemical texts and beyond. Throughout its tenure, it’s represented many things, with the common denominator being duality, and Ales Kot infuses this issue with a multitude of cyclicality and layered recurring through-lines.

To begin with, the team of Elena, Baldwin, and Nick has fallen into absolute shambles, breaking their supposed “always and forever” friendship. While Nick being a loose cannon should surprise no one (after his churlishness throughout the series and his alienating himself from Baldwin in last issue’s one-sided punch-up), he’s also forsaken his relationship with Elena. On top of that, the issue opens with Baldwin confessing his love to Elena who…doesn’t take it well. It turns quite incendiary, actually, leaving Baldwin stunned and alone in a beautiful page from Andre Lima Araujo.

I really love Araujo’s use of lineation to imply movement here, and both the writer and the artist allow the event space to let the moment sit with the audience.

I really love Araujo’s use of lineation to imply movement here, and both the writer and the artist allow the event space to let the moment sit with the audience.

From here, the cast — including Akio and West — figures out Nick’s destination as he runs away: the “place of his wound,” a nuclear power plant related to Nick’s brother’s death. I think it’s quite telling that Kot returns to this idea of “the wound.” Almost three years ago, he wrote the line for the guru in Secret Avengers 9, while speaking to a distraught M.O.D.O.K., “We repeat our wound until we learn to walk through it, instead.” This fits just as well in Generation Gone, wherein Kot writes all of our main characters (save maybe the more stoic Baldwin) with a very clear and dangerous volatility, each put into various states of emotional or physical isolation. While this is status quo for many of Kot’s characters, what strikes me here about the Millenials who act as leads in this title is their immaturity. For example, Nick kills a soldier by throwing a rock at him — perhaps the most schoolyard form of violence possible. Then, as Nick scraps with Elena, he picks her up and drops her on her head in a direct allusion to a tombstone piledriver, a move popularized by the zany, cartoonish, kid-friendly brand of early-90’s pro-wresting. Emotionally, it seems as though many of these characters are becoming regressive into their stunted emotional development instead of growing with the events taking place, and I’m not used to seeing such a slide as a character journey from our protagonists.

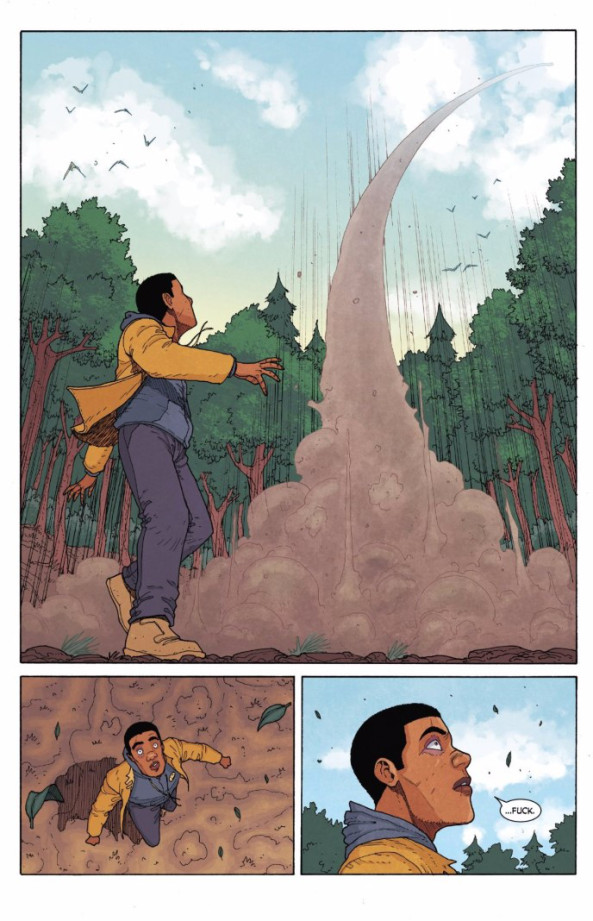

After Nick uses a rock to kill the chopper’s pilot carrying Akio and West, Akio finally gets what he’s been asking for: a chance to talk one-on-one with the recipients of his Project Utopia injection. Here’s where things get crazy. Akio appeals to Nick on a personal level, but an incensed Nick responds to Akio with brutality fueled by newfound super-strength:

Akio is torn in half, and what an apropos style of death. The scientist’s own chosen symbol for the plot-instigating experiment, the ouroboros, represents both creation and destruction, so it, of course, fits that Akio would be destroyed by the very metahuman he created. Even more-so, the ouroboros also stood for a Gnostic brand of duality, that kind of “one is the all” philosophy of the yin and yang, making Akio being split down the middle a great nod to the death of his ideals, as opposing forces he had hoped would co-exist instead tear him asunder.

Mark, did this issue stimulate you in the same way it stimulated me? With a cerebral writer like Kot, I sometimes worry that the reveals and beats here might be impactful on an intellectual rather than the emotional level. Did you find this to be the case, and either way, how did Araujo’s pencils and O’Hallhoran’s inks help or hurt?

Mark: Ales Kot has always struck me as a cerebral writer, but not cold in the way someone like Jonathan Hickman can be. Kot’s brutal, but not detached.

My first exposure to Kot was his run on Marvel’s Secret Avengers, and while that book could at times be very playful and lighthearted, it also dealt pretty honestly with the real-world emotional scars living in a comic book world could inflict. It’s an idea Kot continues to iterate on in Gone Generation 4, only this time there’s very little fun to balance out the darkness. The world feels very different in late 2017 than it did in 2014, and Gone Generation 4 is an appropriately angry response to where “the adults” have led us.

In American politics the past couple of years we’ve seen Donald Trump and the Republican Party tactically give voice and power to alt-right neo-Nazis — angry, young, straight white men like Nick — in their drive for power and control. A generous reading of the past few years would be that they did so inadvertently, but how much does intention really matter at this point? The establishment’s approval of white supremacists weaponized these groups by giving their “concerns” a legitimized platform. The Republicans now face a conundrum of their own making: how do they de-weaponize their alt-right followers without losing their grip on hard-won power?

Akio turned Nick into a literal weapon, a super powered bomb driven by rage, but even when Nick proves to be beyond dangerous, Akio still thinks he can control him for his own purposes. But there’s no off switch. Everyone knows you can’t create a monster and then hope to tame it. Nick ends up ripping Akio apart, but even after Akio dies Nick lives on. The issue ends with him heading towards the nuclear power plant, intent on inflicting maximum carnage.

Gone Generation 4 is not a hopeful issue, but it is an emotionally honest one. The idea that these characters are regressing is counter to what we expect in a narrative, but is very much how real-world human beings react against trauma and change — with a primal thrashing of anger that can be devastating. In Secret Avengers 9 Kot proposed that “we repeat our wound until we learn to walk through it, instead.” In Gone Generation 4 he wonders what happens if we never learn.

For a complete list of what we’re reading, head on over to our Pull List page. Whenever possible, buy your comics from your local mom and pop comic bookstore. If you want to rock digital copies, head on over to Comixology and download issues there. There’s no need to pirate, right?