Do people get to choose the way God looks? Is the face of God different for each of us, dependent on our need, our understanding, our certain sensibilities?

How much does the ethos of the God of our upbringing inform our approach to the world?

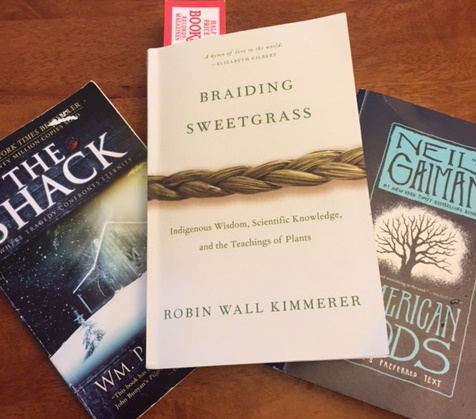

I’m pacing on this pondering path because of three books–books that I was nudged toward this summer: American Gods, The Shack, and Braiding Sweetgrass.

Sometimes books are entertaining, sometimes informing, sometimes inspiring. There are the occasional books that disappoint. And sometimes the themes and images run from one book into the reading of another, very different one. Then I think it’s time to explore that phenomenon. Why these books? Why now? What could I learn from this confluence?

*************

American Gods was a little bit of a departure from the beaten path for me. I’d enjoyed the Graveyard Book. On a whim, I borrowed Gaiman’s Norse Myths from the library–Something different, I thought–and I enjoyed that, too. I compared the images I’d absorbed of Norse gods–mostly from reading my brother’s copies of Thor comic books, back in the 1960’s and ’70’s–to Gaiman’s depiction. There were some overlaps, and there were many differences.

Gaiman’s depictions of the gods made them almost human (although, of course, they were gods), and their motives understandable, if not always admirable. It was fun to read, and my son Jim, excited that I liked one of ‘his’ authors, kept urging me to read American Gods. A TV show was coming up, he said, based on Gods. “You know you hate to watch a show before you’ve read the book,” he urged. So when a Barnes and Nobles gift card came my way, I used it to order the book.

American Gods is Shadow’s story. He is a prisoner, convicted of a pretty serious, although perpetually hazy, crime,–a crime which is never fully explained. But we get the feeling that he’s innocent on some level–that he did what he did as a reaction to something worse that was done to him. That maybe, he did it to protect someone dear. At any rate, he does his time and then, he is released one day early. That is because his wife has died in a car accident. Shadow goes home to bury her, crushed and grieving.

And on his journey, he meets a man. (How many reviews could start with those words?) But the man Shadow meets is also a god, and he offers Shadow a job. One thing leads to another, and Shadow, despite misgivings, accept the offered role.

Shadow meets many people, all of them gods in other cultures, all of them brought to the United States by some sort of immigration. All of them forgotten, reduced to human form and human occupations, and all of them readying for a confrontation with the gods Americans have adopted in their steads–gods like Media, Internet, and Retail Therapy.

The forgotten gods are not all good, or all-knowing, or even, usually, compassionate. Gaiman writes in Norse gods, Celtic gods, gods from Africa and South America. The Egyptian gods of death, Mr. Jacquel and Mr. Ibis, work as mild-mannered undertakers. Native American gods ride a merry-go-round with Eastern European counterparts. They long for the old days, all the gods do, and some of them plan to get their power back.

Why Shadow? Why does Mr. Wednesday choose a grieving, recent ex-con without very many beliefs at all to be his bodyguard and wing man? The story unfolds.

Everyone, Gaiman seems to suggest, has themselves a god or two. Or at least, we did when we were young, and those early gods went a long way to shaping our being.

***************

My friend and colleague Shay loaned me The Shack, by William Paul Young. She was excited about the book; she was excited about the film–available via streaming, she told me. The Shack, I thought, was just the kind of book I do not usually read: a religious fable, a heavy push toward one kind of belief. But I value Shay and the book seemed short enough to whip through, so I said my thanks, and took the dog-eared paperback home.

And I read.

Mackenzie Allen Phillips—Mack–is the main character, and the premise is interesting. Mack was a childhood victim of his father’s horrific violence. In confiding in a trusted mentor, Mack opened himself to a particularly vicious bout of paternal vengeance, He was 13, and he left home afterwards. But first he put rat poison in all of his alcoholic Father’s stashed bottles. The narrative never out and out tells us so, but we believe that Mack killed his father.

And then Mack kicks around, traveling, learning, working hard, getting to the point where he even enrolls in a seminary course. He meets Nan; they marry and have four children.

And then, on a camping trip, the youngest–Missy–is abducted and murdered. Her bloody dress is found in a shack but the murderer is never apprehended, nor is Missy’s body found. Mack enters what he calls The Great Sadness.

Several years later, he gets a message: Meet me in the shack this weekend, it tells him. It is signed ‘Papa.’

Papa is his wife’s name for God.

Again the misgivings. Again, our protagonist takes the unlikely path. Again, he meets his gods.

Mack’s gods are the Holy Trinity. God the Father appears to him as a jolly Black woman who loves to cook. Jesus is a homely, compassionate woodworker. Sarayu is the Holy Spirit, not quite corporal, elusive, maddening, and very, very funny.

I was surprised to find a different kind of message here–not a push toward one belief or religious sect. Mack had to challenge the beliefs he grew up with. The reader is challenged at the end of the book: did the weekend at the shack really happen? And if it was all a dream or a hallucination, does that matter?

*************

I had a pantheon of gods jumbled and competing in my overworked brain. I finished The Shack and thought I’d reach for something different, so I opened the book my friend Terri recently sent me: Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer.

The book opens with Kimmerer’s retelling of the story of Skywoman falling through a hole in the heavens and landing in the vast sea that was then earth. She is saved through the compassion of the animals who help her: the Turtle, who allows her to climb on his back, the muskrat, who sacrifices his life to bring Skywoman a handful of mud from the depths.

Muskrat’s mud allows Skywoman to begin a new world. She places the mud on Turtle’s back; she walks around it, chanting, and the mud grows, deepens, dries, and Skywoman is able to plant the seeds she had with her when she fell. Skywoman, the animals who helped her–they create the earth as we know it. It is a place to be shared.

Kimmerer is an environmental scientist and a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation. The native American gods–she calls their stories the First Instructions–are very real and present to her, and their stories define her belief that earth is a gift to be shared, not just with other peoples, but with all creation.

The Adam and Eve story that informs Christianity and Judaism, Kimmerer notes, has a different emphasis. It teaches that man has dominion over the earth, and that the earth was made for his enjoyment alone. How differently Eve related to the earth than Skywoman did!

“Look at the legacy of poor Eve’s exile from Eden,” Kimmerer writes; “the land shows the bruises of an abusive relationship. It’s not just the land that is broken, but more importantly, our relationship to the land.”

***************

Three very different views of gods; three very different reasons for writing: to entertain, to inspire, to inform. And to challenge. Each view is unexpected–Gaiman’s gods with their rough edges and human foibles; Young’s Papa as a robust Black woman; Kimmerer’s Skywoman, trailing long black hair as she tumbles through the heaven-hole. And the teachings are unexpected, too. Gods can die. Religion can be a barrier and a burden. Humankind is not necessarily the superior race, left by God to be in charge of His creation.

What else, my English teacher’s mind demands, connects these three disparate books?

And I realize it is the connection of place and worship and finding god.

The gods in Gaiman’s novel are unloved because they have been taken from their place of origin. In a new culture, the immigrants who brought them forgot them. They are dying off in an uncaring land.

In Young’s book, Mack must return to the place of his greatest pain in order to find God, who transforms the place of suffering into somewhere understanding, healing, and faith can grow.

Kimmerer writes about the forced migrations of the native peoples in the United States, and of the relation of people as a whole to this earth they inhabit. She writes that relationship to the earth must change–people must relinquish their ownership and share the planet with all who depend upon it.

**************

So I think about place and faith, and I wonder if there’s an effect when people move. What if your parents, and their parents before them, were wanderers? What if you yourself have shifted and moved not once, but several times?

I think of this in the context of a recent visit to home roots–to the sad, abandoned house where my parents first met. There was a pull there, an energy, a little sense of sacred. Was that sacred or was that memory? What happens to faith when it’s uprooted?

*************

I don’t have any answers–I’m not entirely sure of the questions, in fact. But the exploration and conjunction of three very different works with faith and the gods at their cores ignites the questing places in my mind. I’ll have many things to think about as summer begins to wane.

Advertisements Share this: