As I can’t stop repeating it (and if you still haven’t noticed it, you should take a look at my first blog post “the Devil won’t always wear Prada”) I love fashion, I love how its offers a variety of styles and trends and how everyone can find what they heart desire no matter the budget they have. Nonetheless, all is not rosy: ethical and green conditions, especially when talking about fast fashion, often fall into the background in order to prioritise small prices.

One solution: sustainable and ethical brands offering stylish and trendy clothes. However, a battle against this colossus ,aka the fast fashion empire, could be harder than expected.

Once you go Green, you never go back

With an increase of 29.2% on organic and green products in only four years, it is undeniable that the green and ethical market is currently in full expansion. There are multiple reasons that explain that phenomenon. Firstly, thanks to different reports published by official governmental bodies, such as the committee on climate change, and conveyed by the press, people are more aware that global warming and greenhouse gases are a real threat to our planet. Therefore, consumers are becoming more sensitive to organic products. Data is here to prove it since the purchase of organic food increased by 4.1% in 2014 only. Moreover, the fact that organic food offers transparency also plays its part; indeed, after the horsemeat scandal that happened in 2013, people had the need to know where their food came from and what it was made of. Fortunately for them, organic food fulfils all these criteria.

Fast fashion brands, such as H&M or M&S, saw that sustainability, transparency and ethical conditions became more important to their customers’ eye and tried their best to respond to that change. Both brands cited above came up with a recycling scheme; Marks & Spencer came up with the idea of “Schwooping”: every customer would receive a £5 voucher in exchange of a bag full of old clothes. Similar to that idea, H&M would give 0.02 euros to a charity for every kilogram of clothes brought by a customer.

H&M even took their idea further and decided to develop a conscious collection that they describe as being “available, affordable and attractive to as many people as possible”. They ensure their customers that the environment and the ethical conditions of their workers are at the heart of this project. However, when I first read the webpage concerning their conscious collection, all I could think about was “hypocrisy”. They claim that “sustainability is a word of action. A mission that is built on passion, long-term thinking and teamwork.” However, a quick look on the Internet allowed me to discover numbers of scandals that happened in different factories owned by H&M: Syrian children found in a factory in Turkey6, 8000 workers who have collapsed since 2010 in a factory in China, underpaid employees, etc… All these facts make me question the honesty and the reliability of brands such as H&M and especially make me wonder if what they affirm about their “conscious” collection is true.

As a Millennial, I think we deserve a brand that associates real ethical and sustainable conditions with trendy and affordable clothes.

Nock, Draw, Loose!

Millennials would be a perfect target for a brand that would be ethical, sustainable, fashionable and mainly sold online. These tech-savvy beings (89% of them use the Internet on their smartphone everyday) are believed to be better informed about the environment and ethical conditions. Thanks to that, Millennials are caring more about the environment and are trying to contribute to the preservation of our planet, with 65.9% of them buying organic food regularly. An important part, 42%, of vegans are Millennials; and who could claim to be better at protecting and preserving the environment than vegans?

The following infographic will help you to catch up on that “new” way of living that has been experiencing an important growth in popularity lately.

So, would Millennials be ready to buy green and ethical clothes even if the prices of the different garments would be a bit more expensive than the ones found in a typical fast fashion store? This is what I tried to find out by conducting a Qualtrics survey.

I launched that survey at the end of February and gathered 85 responses from people aged 18 to 64. I extracted the answers given by Millennials from the others, and here is what I found:

More than half of them (50.7%) declared to be influenced by the ethical/green standards of a brand when they buy a piece of clothing; 57.7% of the Millennials surveyed claim that they would agree to spend more if the brand used organic raw materials and textiles made of recycled old clothing. However, what surprised me is the fact that almost 82% of them would agree to spend more if the brand acted in an ethical way.

These results show that people are willing to change their habits and to contribute, in their own way, to a better world in term of sustainability and ethical conditions.

Who’s afraid of the Big Bad Fast Fashion? Not Millennials

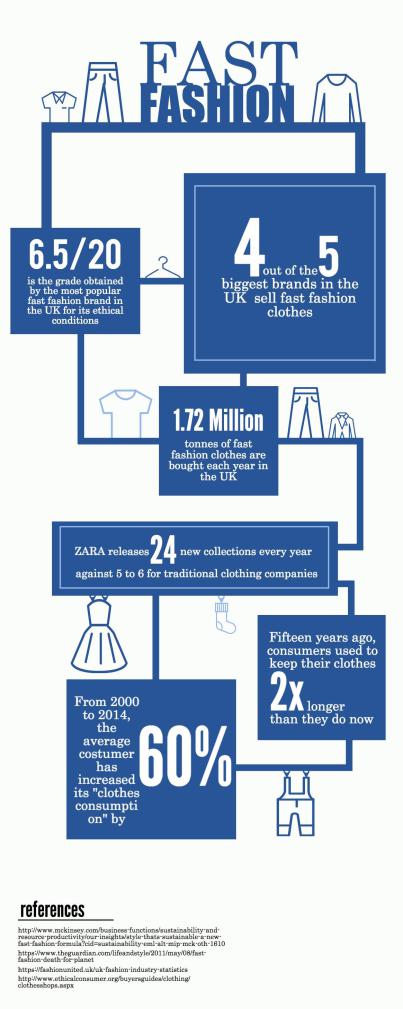

However, as I said it in my introduction, the fight against the fast fashion industry is far from being over. Indeed, companies such as H&M or Primark are massive, with a turnover of £1’013’202’000 for H&M UK Limited in 2015 only and a net sales retailing of £3’140.7 million for Primark in 2016; to compete against them would be hard because they manage to offer trendy clothes, small prices and also a big variety of collections, that change up to every two weeks. This infographic gives you a better understanding of how big and popular fast fashion brands are in the UK.

However, this is where a paradox starts to appear: even if more than half of the Millennials surveyed would be ready to buy green and ethical clothes and even spend more money on them, they still are the main costumers of fast fashion brands such as Primark or H&M. YouGov customer profile describes the typical customers of H&M as being female, 18-24 (therefore being a Millennial) and regular customer of Primark. With a monthly spare of only £125- £499, I can understand that this typical customer would choose to shop fast fashion clothes because of the cheap prices that they offer. However, when I took a look at two other fast fashion brands, Topshop and Topman, I discovered that both regular customers were Millennials and had a monthly spare of £500-£999. What could then explain this buying behaviour? This is where buying behaviour theories come into play.

Serene on the outside, conflicted on the inside

Cognitive dissonance is a state a customer is in when faced with two choices (or more) that involve two opposed behaviours. Therefore, to minimise that feeling of discomfort, the customer will go through a cognitive dissonance reduction process and will find ways to overcome the dissonance that occurs in their mind. Let’s apply this theory to our case: Sophie, 21, loves shopping at Topshop because she feels like she can always find clothes that are on trend and not too expensive. However, Sophie is aware that big industries such as Topshop have poor ethical and green conditions and she thinks it is immoral of them. Thus, here is the cognitive dissonance: on the one hand, Sophie has trendy and affordable clothes; on the other hand, she knows that buying fast fashion clothes harm the environment. To resolve the conflict taking place in her head, she either won’t buy the cute top she saw in Topshop OR she will try to find reasons why she wouldn’t have to feel guilty purchasing that top. The reasons could be various: she could question what she read in the newspaper, wondering if all the scandals are true; she could also tell herself that not buying that top won’t make a difference because everyone shops fast fashion clothing anyway. However, what could help her choose which option to use to reduce the dissonance?

The consumption values theory has the answer to that question. Indeed, this theory affirms that buying behaviour are influenced by five different values: the functional, conditional, social, emotional and epistemic value. Regarding Sophie and her dilemma, two values are involved. The functional value and the emotional value.

The functional value because she knows that buying that top is a safe choice in term of its price but also in term of its reliability, i.e it will be on trend.

The emotional value because not buying that top would make her feel good and give her the impression that she’s contributed to a greater cause.

However, the functional value is assumed to be the key influencer when a customer hesitates between different alternatives. Thus, it explains why Millennials claim caring about the environment but still are the main customers of fast fashion brands.

“Buy less, choose well, make it last”

Vivienne Westwood

Our planet and environment are already severely endangered; these very wise words summarise well the state of mind that everyone should move towards if we want to eradicate the fast fashion empire and its awful ethical and green standards.

Advertisements Share this: