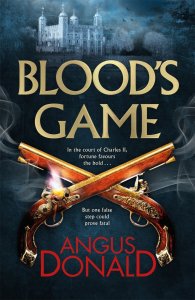

Hi guys! Today is the say when the new historical fiction series novel Blood’s Game by the bestselling author, Angus Donald, is published. What makes this novel particularly interesting is that Angus Donald is a distant relative of the protagonist, Col. Thomas Blood who famously stole the Crown Jewels from the Tower of London in 1671 – brilliant, no? I am incredibly looking towards reading the book but in the meantime I have a guest post from the author!

bestselling author, Angus Donald, is published. What makes this novel particularly interesting is that Angus Donald is a distant relative of the protagonist, Col. Thomas Blood who famously stole the Crown Jewels from the Tower of London in 1671 – brilliant, no? I am incredibly looking towards reading the book but in the meantime I have a guest post from the author!

The court of Charles II: mistresses, mischief and merry-making

By Angus Donald

I’ve always enjoyed a little debauchery – I don’t get to indulge so much these days, now that I’m middle-aged and married with two young kids, but I’ve done more than my fair share of wild partying over the years. And I must admit that it was partly this deplorable character failing that drew me to write about the Restoration period and the “Merry Monarch” Charles II – it sounded like a hell of a lot of fun!

My new novel Blood’s Game, a tale about the attempt by Colonel Thomas Blood to steal the Crown Jewels from the Tower of London, opens in 1670, ten years after Charles was restored to his thrones in the Three Kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland. Once back in power after a long penniless exile, the King was determined to have a really good time. He travelled back to London from the Kentish coast in a glittering procession, dressed in a silver tunic, his path strewn with fragrant herbs by beautiful maidens, the public fountains in the capital all running with wine. He continued this display of largesse throughout his reign; he spent money he didn’t have on fabulous masked balls, parties and banquets for his friends, he bought rare jewels and thoroughbred race horses, he gave extravagant gifts and grants of lands to his many mistresses and their offspring – by 1670 he owned eleven royal yachts and was about to buy another for his unhappy Portuguese wife Catherine.

His ministers tried to rein in his spending but, even though he received more than a million pounds a year from Parliament, his expenditure always far outstripped his income. But, as Charles says in Blood’s Game: “A certain carelessness with his finances befits a monarch. I refuse to scrimp and snivel like some damned pauper.”

The King was deliberate about this policy of having fun: the Three Kingdoms had just come out of a long dark period when the bloody civil wars were followed by the Puritan rule of the Commonwealth and Oliver Cromwell. During the austere interregnum period, most sports were banned, drunkenness and even swearing was punished with a fine, non-religious expressions of Christmas were stopped, many inns were closed, as were all the theatres, women caught working on Sundays were put in the stocks, bright clothes were banned and make-up was scrubbed off girls’ faces by soldiers who caught them wearing it, right there and then. Armed men humiliating women in the streets in the name of religious purity does not only happen in other parts of the world. We had our own approximation of the Taliban once.

So, when Charles returned to the throne, he wanted to show his subjects that it was now perfectly all right for people to enjoy themselves. Hip hip hooray! The theatres were reopened, and there was a resurgence of bawdy, satirical plays. Public drunkenness, particularly among the aristocracy, was so commonplace as to be almost a badge of rank. Pranks and japes abounded – a pair of well-born young men, friends of the King and members of the notorious Merry Gang, scandalised London by appearing on a balcony and pretending to sodomise each other. Poets and playwrights could openly criticise the King, his court, his morals and his mistresses. And did so enthusiastically. The drunken poet John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester, leader of the Merry Gang, wrote of the King in one satire: “Restless he rolls from whore to whore/ A merry monarch, scandalous and poor”

Because Charles took his sexual pleasures seriously, too. He had many lovers as a young bachelor, including his nanny Mrs Wyndham, who took his virginity when he was fifteen. And after he married Catherine of Braganza, in 1662, he had at least seven mistresses, and possible as many as thirteen, who bore him a dozen children.

The role of mistress was semi-official – a whore or courtesan, or woman with whom the King had a casual encounter, would not counted among their number – and a man who kept one was obliged to pay for her food, drink, accommodation and servants, as well as making her generous presents from time to time, perhaps when he paid them a visit. Many of the mistresses and their illegitimate children, whose paternity the King acknowledged, received earldoms and dukedoms from the King – and many of British aristocrats alive today trace their ancestry back to Charles II.

Two of the the most famous of Charles’s mistresses – the formidable beauty Barbara Villiers, Duchess of Cleveland, and the famous actress Nell Gywn – make appearances in Blood’s Game. In the period when the book is set, Barbara was about thirty and was being replaced in the royal affections by the feisty and outrageous Nell, who was ten years younger. Gwyn was an actress, and before that an “orange-seller” in the theatres, a profession which some historians take as a euphemism for prostitute. Perhaps because of her lowly origins and dubious trade, she was never ennobled by her royal lover, although her two children were.

Barbara, on the other hand, came from the noble Villiers family. She gave Charles five children and, as a long-time and fecund mistress, she wielded more power at court than childless Catherine. In fact, she was known as the Uncrowned Queen and she used her position ruthlessly to enrich herself and her friends. She persuaded the King to grant her lavish titles and lands and properties – she was given Nonsuch Palace, built by Henry VIII, and the title Baroness Nonsuch, and promptly dismantled the palace and sold off the building materials to pay her gambling debts. She “borrowed” tens of thousands of pounds from the Privy Purse, and when this was discovered, the debt was immediately forgiven by her indulgent lover Charles.

When Charles’s interest in her began to wane, she was not above finding other gentlemen friends to amuse her. She became the lover of Jack Churchill, the future Duke of Marlborough, when he was a handsome and penniless young officer at court. She bore Churchill a daughter and tried, unsuccessfully, to claim she was the King’s.

Charles was not exactly delighted that his long-time lover, a woman he had given so much to, had taken a younger man to her bed – Barbara had given Churchill a gift of £5,000, money she had received from the King, which infuriated Charles – but he was perfectly gentlemanly about the situation. He was, after all, beginning his relationship with Nell Gwyn at the time. There is a (probably apocryphal) tale, which I have included in Blood’s Game, that a servant was paid £100 by the Duke of Buckingham to inform His Grace when Churchill and Villiers would next be enjoying a lovers’ tryst. The mischief-making Duke then persuaded the King to visit Barbara at the same time. The story goes that when the King arrived unexpectedly, the naked Churchill had to hide in a cupboard, and was discovered there by the Merry Monarch.

Apparently, the King saw the funny side, and forgave his love rival. He said: “You are a rascal, sir, but I forgive you because you do it to get your [daily] bread.”

A stinging insult – basically calling Churchill a man-whore – then forgiveness. And never losing your sense of humour. That’s pure class in my book. And the lusty King even hung around to pleasure his old mistress after young Churchill had gone.

How could writing about a monarch like that, and chronicling his court of drunken, debauched and promiscuous hangers-on, not be the most tremendous fun?

I hope you find reading Blood’s Game just as enjoyable.

Advertisements Teilen mit: