(Messrs Ford, Joyce, Pound and Quinn: Paris, 1923)

Today is the birthday of Ford Madox Ford, born Ford Madox Hueffer in Merton, Surrey, 17th December 1873. Even excluding the several pseudonyms he used, there are plenty of other versions of his name, many of them—such as ‘Forty-Mad-Dogs Hueffer’—traceable to the always inventive Ezra Pound.[1]

I tend to mention Ford a lot because he comes easily to mind, my mind anyway (among an increasing number of other minds). But then anyone interested in modern literature will probably have read his The Good Soldier; anyone really interested in modern literature will probably have read, or intended to read, or at least know something about, Parade’s End, his superb tetralogy about England before, during and after the Great War. ‘About England’—that is to say, about landscape, class, gender, love, sex, history, politics, social conventions, religion, psychological breakdown—and other things.

Ford was always attentive to anniversaries, Saints’ days—and birthdays, not excluding his own. According to the dates given at the back of the book, he began writing When the Wicked Man—not one of his best novels, by a country mile—in Paris, on 17 December 1928 (he went on with it in New York and finished it aboard R.M.S. Mauretania, off the Scillies, 1 December 1930.) More famously, we find this claim in the ‘Dedicatory Letter’, addressed to Stella Bowen, which first appeared in the 1927 Albert & Charles Boni edition of The Good Soldier: A Tale of Passion:

‘Until I sat down to write this book—on the 17th December 1913—I had never attempted to extend myself, to use a phrase of race-horse training. Partly because I had always entertained very fixedly the idea that—whatever may be the case with other writers—I at least should not be able to write a novel by which I should care to stand before reaching the age of forty; partly because I very definitely did not want to come into competition with other writers whose claim or whose need for recognition and what recognitions bring were greater than my own. I had never really tried to put into any novel of mine all that I knew about writing. I had written rather desultorily a number of books—a great number—but they had all been in the nature of pastiches, of pieces of rather precious writing, or of tours de force. But I have always been mad about writing—about the way writing should be done and partly alone, partly with the companionship of Conrad, I had even at that date made exhaustive studies into how words should be handled and novels constructed.

‘So, on the day I was forty I sat down to show what I could do—and The Good Soldier resulted.’[2]

In his lifetime, Ford published almost eighty books: say seventy-eight if we don’t count The Panel and its slight revision for American publication, Ring for Nancy, as separate items. For numerologists, 2017 has been the seventy-eighth year since his death. (Ford studies take many forms, some of them a little worrying. Mais passons.)

And I see that I read my first Ford book – good grief! – forty years ago. (Acutely numerate Ford scholars might narrow their eyes at this point, suspecting a massaging of the figures—‘Really? Exactly forty?’—but you can trust me on this.)

People occasionally ask, ‘Are there any others that are really good?’ I try to be scrupulous in separating the ones that I think are ‘really good’, say a dozen or so, maybe more, from those that have points of interest for the Ford specialist (just about all of them). Keeping it tight: if historical novels, particularly set in the Tudor period, are your thing, you may already have come across The Fifth Queen trilogy. It centres on Katharine Howard and on a chap called Thomas Cromwell, not an unfamiliar name these days. Then I’ve always had a fondness for The Young Lovell, set in 1486, concerning magic and a belle dame sans merci; and Ladies Whose Bright Eye, set in the fourteenth century (though with one foot in the twentieth), which might just edge it, because of its high spirits.

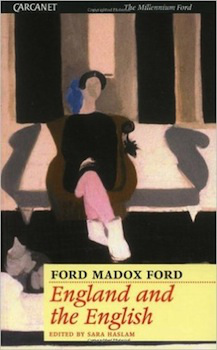

Then England and the English, which is cheating slightly since this is another trilogy, comprising The Soul of London, The Heart of the Country and The Spirit of the People. Joseph Conrad: A Personal Remembrance was written at speed in the months following Conrad’s death. Ford refers to it as a novel but it gives a much more vivid sense of how Conrad actually was than many scrupulous biographies of him. No Enemy, written mostly in 1919, was published in America ten years later (and first published in the UK seventy-three years after that). Dancing along the border between fiction and autobiography, it has folded into it many of Ford’s experiences and perceptions of the recent war: suffering from shell-shock, he had, in effect, to learn to write again.

From Ford’s final decade, I’d probably pick It Was the Nightingale just ahead of the outrageously enjoyable Return to Yesterday; and Provence would just edge out the slightly more eccentric Great Trade Route, so Ford’s beloved adopted home rather than the embodied idea and the sometimes uneasy grappling with the American South.

That, of course, leaves out of account entirely the poetry, the critical essays, the letters, the fairy tales, the art criticism. . . Still, it’s a start.

And of the two heavyweights? People sometimes ask: Coleridge or Wordsworth? Eliot or Pound? Lennon or McCartney? The Good Soldier or Parade’s End? I say: both, though acknowledging that, on the quiet, one leans this way or that.

(Adelaide Clemens as Valentine Wannop, Benedict Cumberbatch as Christopher Tietjens

in the BBC/HBO adaptation of Parade’s End)

‘The day of her long interview with Tietjens, amongst the amassed beauties of Macmaster furnishings, she marked in the calendar of her mind as her great love scene. That had been two years ago: he had been going into the army. Now he was going out again. From that she knew what a love scene was. It passed without any mention of the word “love”; it passed in impulses; warmths; rigors of the skin. Yet with every word they had said to each other they had confessed their love; in that way, when you listen to the nightingale you hear the expressed craving of your lover beating upon your heart.’[3]

Yes.

References

[1] This one crops up in Pound’s interview with D. G. Bridson, in New Directions 17, edited by James Laughlin (New York: New Directions, 1961), 166. Another version was ‘Freiherr von Grumpus ZU und VON Bieberstein’: Brita Lindberg-Seyersted, editor, Pound/Ford: The Story of a Literary Friendship (London: Faber & Faber 1982), 141.

[2] Ford Madox Ford, The Good Soldier: A Tale of Passion (1915; edited by Max Saunders (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 3.

[3] Ford Madox Ford, Some Do Not. . . (1924; edited by Max Saunders, Manchester: Carcanet Press, 2010), 322.

Share this: