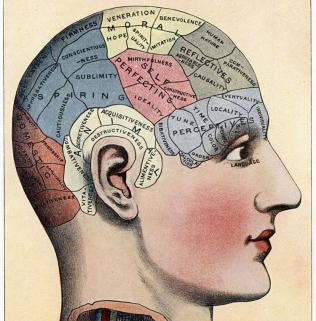

A few years ago, I read a very interesting book called What We See When We Read by Peter Mendelsund. It was a work that explained what we see in our mind’s eye while we read, how our brain processes and rewrites information, and why my Anna Karenina is not Tolstoy’s or yours. It was a fascinating and visual book, but said a lot that I had already guessed from my own experience reading. I was less interested in what I saw when I did the act of the reading and more interested in how we remember what we read. Most of what I read is narrative fiction. I remember every novel I read in four different ways, that is to say, I have four simultaneous versions of the same book in my head. The first version is the one received while reading: the one that Mendelsund talked about in his book. The second is the linguistic imprint of the book. The third is the version that is uniquely my own, which I have patched up and filled in with alternate endings and extra backstory. And the last is the one that is influenced by outside knowledge of the author or society, or the extra-textual reading of a novel. These ways of recalling literature are a topic that I have talked about with friends and family extensively. It seems to be something that everyone does subconsciously. Over the past few years I’ve written several versions of this essay, trying to find the words to explain this complex process. I still have not found the perfect words, but I’m getting there.

If I think about a book, I might think of any number of things related to it – the language, conversations I’ve had regarding it, and so on. But when I think about when I read a book, the act of reading it, I remember it as a series of vivid and complex mental images, almost dreamlike. It is what my brain received and processed while first reading. This initial imprint of a book on your mind is not tainted by the author’s childhood home, any literary analysis, or what the film version looked like. When you read, you read so quickly that your brain can’t completely process everything, so you can end up with something completely incorrect. I can disregard what the author is telling me in favor of my own imaginings. When I am confused about a plot point, I can ignore it. If I don’t really know what a Russian farm looks like while reading Anna Karenina, I will replace it with a North American colonial farm. While reading a sci-fi like Hitchhiker’s, I can fill the gaps of world-building with any number of composite images, or I can keep holes in the scenery when I just don’t know what’s there.

These first impressions are what make or break a story for the reader. I believe these first impressions are what creates “favorite books.” They determine which stories you want to reread and which worlds you want to revisit. For example, Life of Pi was such a vivid and complex experience for me that, even though I don’t love the book, it will stick to me much closer than a similar genre novel like Bee Season. If these first impressions are simply our own imagination’s response to a story or image, then it’s not really our choice when we love a book or the author’s fault when we don’t. How well you processed the information on the first read can be influenced by any number of factors outside of your control. My first impression of Howl’s Moving Castle is so strong and unique that it instantly became and remains a “favorite book.” My friends, who love Diana Wynne Jones, all love her for their own reasons. My Howl is not anyone else’s. Wynne Jones gave such excellent bones and ready bodies that a reader can clothe Howl and Sophie in whatever they please and the product is still at heart the same. Wynne Jones gave us characters who are symbolic, dramatic, and very malleable. But he is always still Howl Pendragon.

Other authors like George RR Martin don’t give the reader much visual creativity. He is talented at giving huge amounts of information very simply. Naturally, every reader views Kings Landing slightly differently, but it is the overwhelming agreement that readers share that makes the series easy to talk about and love in community. I know many people who love Howl, but we cannot sit down and talk about Howl the way we talk about Jon Snow. This is the mystery of writing and imagination. Somehow Jon is a “known” factor, and readers are in agreement. Like a friend we all knew in high school, we know Jon as a group. You might have slightly different experiences with him – different memories – but it’s still Jon. Howl is different. Howl is an idea and powerful symbol, and ultimately he is mine. I can’t share my Howl with you. I wouldn’t know how to.

This first impression of a novel is often very blurry in unclear places. But it is also this version that smells good and tastes good. To quote Hemingway, “All good books are alike in that they are truer than if they had really happened and after you are finished reading one you will feel that all that happened to you and afterwards it all belongs to you: the good and the bad, the ecstasy, the remorse and sorrow, the people and the places and how the weather was.” This vivid and memorable world is what I encountered when first reading Rebecca. When the narrator has breakfast for the first time at Manderly, those words are more than words; they are flavors that have imprinted themselves in my memory. Another reader might not have been so influenced by the “tea, in a great silver urn, and coffee too, and on the heater, piping hot, dishes of scrambled eggs, of bacon, and another of fish. There was a little clutch of boiled eggs as well, in their own special heater, and porridge, in a silver porringer. On another side-board was a ham, and a great piece of cold bacon. There were scones, too, on the table, and toast, and various pots of jam, marmalade, and honey, while dessert dishes, piled high with fruit stood at either end.” I don’t have to ever read Rebecca again to remember the flavors of the meals. It’s real.

Regardless of how well you liked the plot or the characters or the writing, your first impression of a story is the one that is alive and vibrant and moves. It’s the one that lives in you, actively, always. I know some readers who are not as visual, and their memory of this initial impression of a novel isn’t as strong, but everyone has one. It’s what your brain does upon reading. How vivid or powerful these memories are for the reader depends on the skill of the author, as Hemingway said, but also partly on the reader’s imagination.

When I think about a novel I read, the second version that comes to mind is what I’ll call the “linguistic” impression, for lack of a better word. An author’s words and phrases are what makes up a book, what gives readers the chance to imagine and “see.” After reading anything, I have produced both the initial visual memory and the initial linguistic memory. Which of these is more dominant in my memory has to do with the author and style of book. In Everything is Illuminated by Jonathan Safran Foer we are transported to pre-WWII Odessa. I don’t have a clue what life looked like there. The best I can come up with a peasant in a kerchief. My initial visual version of the novel is blurry and woefully incomplete. When I remember Everything is Illuminated, what comes to life are the words.

When I was a child, I memorized poetry. I have an awful verbal memory when it comes to reciting but a rather impressive verbal memory for written word. I can approximate the map of words on the page in relation to the length of a book, making it easier for me to find particular passages in long novels. (I’ve found this the biggest issue with Ebooks. You can’t flip.) My ability to remember where passages lay in a book isn’t unique to me – I think it must be a skill that people who read heavily develop with time. Like a language you only know a little off, you can understand and place the general idea and little phrases, even if you couldn’t dictate the whole page.

Everything is Illuminated is like that for me. The following quote is important in terms of character development, and it has its place in the story, but most of all it’s just beautiful. I’m going to try and write it out from memory: “Lunch in a bowl: I don’t love you. Bark on a tree: I don’t love you. Poem too long: I don’t love you. Fence post: the shape of you, the feel of you. I don’t love you. Nothing is more than what it is. Everything is a thing, complete in its thingness.”

I just wrote that out from memory. The real quote is, “Bark-brown fence post: I don’t love you. Poem too long: I don’t love you. Lunch in a bowl: I don’t love you. Physics, the idea of you, the laws of you: I don’t love you. Nothing felt like anything more than what it actually was. Everything was just a thing, mired completely in its thingness.” I never tried to memorize this, but the power of that quote stuck with me so that when I close my eyes I can guestimate the words and recreate them to an extent from memory.

Words are harder to talk about than things. Words hold more meaning, or can hold more meaning, because they represent things and are are subject to interpretation. Every book has a quote or a turn of phrase that sticks with me. Sometimes it’s a small phrase that I will add to my vocabulary afterwards. Sometimes words in narrative fiction are important outside of the context of their scene, because they are doing work beyond simple description. They are teaching you and delivering a concept beyond the physical scene.

“Only a moment. Dionis broke away sobbing. She ran down the path toward home. She did not once look around. She had not said ‘yes’, she had not even said ‘good-bye’. Yet, as she ran, there came upon her again that sense of belonging to Jetsam–that terrible, intimate sense of responsibility for him. She could not tell whether it was intense gladness or intense sorrow.” This quote ends one of my favorite books, Downright Dencey. When I read it, I don’t see her. Instead I feel the concepts behind the words, the universalness of a girl, breaking away from a kiss, crying. That sense of responsibility she has for Jetsam is not just Dionis’ feeling. It is mine as well, and it can be and yours if you’ve ever loved or felt responsible for someone. This quote is a picture of love beyond that one girl’s feelings. It’s the symbols and archetypes behind the words and behind the scene that makes it so memorable.

Then, naturally, there are passages in narrative fiction that stand apart from scene or story. These passages evoke the thoughts and feelings outside of the narrative in order to teach you something, to show or share something bigger than a story. “I believe in an impersonal god who set the universe in motion and went off to hang with her girlfriends and doesn’t even know that I’m alive. I believe in an empty and godless universe of causal chaos, background noise, and sheer blind luck… I believe that life is a game, that life is a cruel joke, and that life is what happens when you’re alive and that you might as well lie back and enjoy it.” This quote from American Gods lives outside of Neil Gaiman’s story. It tells its own story. Language in a book can have dozens of functions. Some passages have no purpose beyond getting specific information across and there are the passages that can stand alone outside of the story, and need no context to be understood or appreciated. Then there are passages that rely on the context of the novel to bring out the beauty or humor or general meaning.

Sometimes I steal words from the authors and misuse them. In Little, Big, a multi-generational fairy tale set in turn of the century New York, a character says, “I don’t know! All I know is that I love him and that’s enough; I want to be with him, and be good to him, and make him rice and beans and have his babies and… and just go on and on.” This quote makes a lot more sense within the context of the story. But it’s also up for grabs. I quoted part of it once in conversation, not even realizing I was plagiarizing. And I don’t think I really meant it in the way the author meant it, but I still said it. Excessive reading helps me to see my own life in perspective, put words to emotions I can’t vocalize. And on occasion, I have used they memorized phrases as my own.

Sometimes when I remember a novel I remember things that aren’t real. It’s the version that is full of the changes and edits that I make purposefully or accidentally – scenes abridged, information assumed, missing scenes I imagined. I don’t always do this consciously, but if a scene bothers me, an outcome upsets me, or if a few hundred pages in the author decides to tell me a character who I imagined to be blonde was actually brunette… I have the choice to accept it or change it. While reading Atonement, when Briony (and likewise McEwan) admits to the reader (you) that Robbie and Cecilia were actually never reunited, what do you do with the blurry future you’d made for them in a cottage with a baby and a cat? You probably did not consciously build it in so much detail but when you’re robbed of it. Suddenly something your mind had unwittingly created no longer has a place in the story, but it doesn’t disappear. You imagined it prematurely, but your mind has already filled in those gaps and you can’t get rid of that imagination.

When you read you are constantly predicting the next pages or chapters. Some of these predictions are forgot in half a page. Some of these predictions stick with you the whole way through and, when are proven false, have no where to go. I did this more as a child, when I would try to fix books I was dissatisfied with or fill out futures for characters. For Johnny Tremain I have backstory and an entire future for Johnny. I invented it when I was very young and felt the book was incomplete. When I read the real text of Johnny Tremain, I can also call up my backstory. My brain has no use for it, but remembers it anyway. Usually these extracurricular voyages your imagination takes are harmless. But there have been times I have reread a book, years later, and found something missing. Something I really thought was there. A conversation. A sentence. A description. But it was never there. I made it up.

When you read you are constantly predicting the next pages or chapters. Some of these predictions are forgot in half a page. Some of these predictions stick with you the whole way through and, when are proven false, have no where to go. I did this more as a child, when I would try to fix books I was dissatisfied with or fill out futures for characters. For Johnny Tremain I have backstory and an entire future for Johnny. I invented it when I was very young and felt the book was incomplete. When I read the real text of Johnny Tremain, I can also call up my backstory. My brain has no use for it, but remembers it anyway. Usually these extracurricular voyages your imagination takes are harmless. But there have been times I have reread a book, years later, and found something missing. Something I really thought was there. A conversation. A sentence. A description. But it was never there. I made it up.

Usually the longer a book is and more you read it, the more complex your additions can be. In my mind, Kitty Bennet and Maria Lucas become best friends with Georgiana and spend summers in Pemberly with Lizzy. I have never read one of those bogus Pride and Prejudice sequels. I don’t want to because I have my own. I first read Pride and Prejudice when I was eleven. That’s well over ten years for my imagination and sort of “personal” fanfiction to settle in with the reality of the novel. I like it more than whatever Death Comes to Pemberly or Mr Darcy Takes a Wife might have to offer.

The version of a novel that holds all my predictions, aborted futures, and abridged endings is fluid. I am a very imaginative person – it’s why I read so much in the first place. So, though I can’t control creating the additions that I give stories, I do choose to keep them around. It’s a very personal process, and one that I wouldn’t even know how to share. Often it disregards the author’s intent; most of the time it is just superfluous. My overactive imagination never affects my enjoyment of the actual novel. Atonement is so powerful because Robbie and Cecelia never live to find each other. Johnny Tremain is so memorable because there’s a good chance he won’t make it out of the war alive. I wouldn’t actually change those endings for the world. The authors knew what they were doing and did it well. But I still have the memory of the little worlds that I built around the stories. I think that’s the beauty of rereading. Reading a novel is very personal, and it’s very powerful too. Authors never really get the final say. They share their world, vision, story, characters, and philosophies. They give it up – and then it’s yours to play with.

There is one last way to recall a novel, the extra-textual version. A memory of the novel which can be tainted or enhanced by literary analysis and historical fact. When I visited Louisa May Alcott’s home in Massachusetts, I had to realign Little Women with that home. It did not rob me of my initial impression from the novel – I’d read it too often and too long ago. You can’t just edit your imagination. But somewhere in me, I took her real home and sectioned it off with other alternate Little Women universes, like I had with film versions. Even a bad film adaptation will never ruin a book for me. Even if I have seen the movie first, I tend to read the book with fresh eyes. However, that information stays with you somewhere. Sometimes it bleeds over. When I reread The Hunger Games, I see the characters and districts as I first imagined them, but I see the arena from the films. I somehow lost my initial imagination of the arena and replaced it with the film version.

This very analytical memory of a novel can be influenced by personal experience as well as added knowledge of an author or time period or the added aesthetic of film versions. When I visited Switzerland, I was able to visualize Heidi better. But I still held onto the “false Switzerland” that I had invented as a seven year old, faced with the concept of Switzerland for the first time. However, my original Switzerland was actually not terribly inaccurate. Fields with wildflowers, I have learned, look pretty similar the world over.

Of course, this is often a bit messy when your knowledge precedes your reading. Even while writing this, I realized I had read the entirety of A Farewell to Arms imagining Frederic Henry to look like Nick Miller from the Fox comedy New Girl. Trying to rationalize this, I realized Nick loves Hemingway in the tv show and mentions him often. Also, Ernest had named a fictional version of himself Nick Adams in a series of stories he’d written in Paris. Those facts together turned Frederic Henry into the actor Jake Johnson.

The two biggest ways you can affect your memory of a novel post-initial-read (apart from film versions) is by learning about the author’s life, and by literary analysis. Some historians and authors protest that a book should never be influenced by the author’s life or his or her intentions. Intentions are not what is important. It is the reader’s own natural understanding that is important. That is the purest form. Conversely, there are historians and authors who believe a book has not been understood until the author’s voice has been added back in. I don’t know which camp I fall into. I think it depends on the book. Normally, I go into novels blind. I read books knowing nothing about them except their title. Recently, I read a book called The Tipping Point because a friend said I should. It wasn’t until I began it that I realized it was nonfiction. I like being completely surprised. I find this to be the most pleasant way of experiencing writing. I don’t even read back covers. I like new worlds, sight unseen. I read The Painted Veil like this. Afterwards, possibly because I disliked it so much, I researched the author and read different analyses to try and figure out out where it had come from. I still didn’t like it.

The author wrote the book. An author can protest that they were “given” a story, or “found” a story, but ultimately, it came from them. But I also think you can enjoy a book without being bridled by interpretation. If an author is living and has been quoted giving information of value, a key to the book, that they want to share with their audience, I think that can be important. But the debate as to authorial intent in novels written by people dead for centuries seems rather meaningless. It’s interesting for sure, and I love reading literary criticism. But don’t let it affect the bones of the book. These opinions, these interpretations – they can be a lens through which I can choose to look. That being said, they can’t be the only way to view a story.

Ultimately, I don’t care who wrote Shakespeare’s plays. I think it was one guy named Shakespeare because that is easy to believe. I just know that I like his plays. For most books, I think the analysis and the critical readings are optional. After an initial read, when you have created the visual version and the linguistic version, after you have developed your own little histories and side stories… then you can research. Then it’s safe to adjust the novel based on the author. If you make that adjustment too soon, or if you take what you find too seriously, it might ruin the whole thing for you. I try to forget CS Lewis wrote Narnia. I just want to love Narnia with the purity of a kid. Now that I’m older, I can read the critique The Magician’s Book: A Skeptic’s Adventures in Narnia, and can apply that knowledge to my memory of the series without tainting the purity of the stories. I know that Rebecca is a dark and twisty novel, but I like being able to remember the simple, visual world I had created on the first read, the narrative without the analysis.

Fin

The more I read, the more impressed I am with the human brain. I can’t believe the amount of information I have processed in my lifetime of reading. I can’t believe how much of it I can remember off-hand years later. These four different memories I have of a novel are not separate in action, only in theory. In practice they blend together, to remind you of the wonderful specifics of a certain novel. I think that if you’re able to understand how you remember what you read, even if your process differs from mine, it will help you remember stories and words in more detail, improve your memory and understanding, and overall enhance the already magical, unexplainable act of reading.

Sarah V Diehl

Advertisements Share this: