Hyenas (Hyènes) is the story of a wealthy woman’s return to her penurious hometown after decades away. The idea of her homecoming is a vignette Africa is well aware of. Her riches are enticing and her people are swelling with optimism. But reprieve is to come at a high price for this community. She offers her people the come-up they desire only if they kill the man who did her wrong when she was pregnant with his child. As soon as the proposition is made, this man is doomed. The town is promised all the millions in the world, but we know its people would have souled their souls for a lot less.

This is the basic plot for Djibril Diop Mambety’s 1992 film, almost a spiritual sequel to Touki Bouki (Journey of the Hyena). Adapted from a Swiss-German stage satire called The Visit, assigning a definite label to Hyenas isn’t easy. There are streaks of satire and black humour but it is also quite the compelling vengeance piece. The man whose life will hang in the balance is the jolly Dramaan Drameh (Mansour Diouf), a shopkeeper well-liked his Colbane townsfolk basically because he never shies away from dishing out stuff on credit or for free. “Because of you my wife despises me,” he tells some men as he pours out free booze for them. Given his white beard, calling him the Colbane Santa wouldn’t be farfetched.

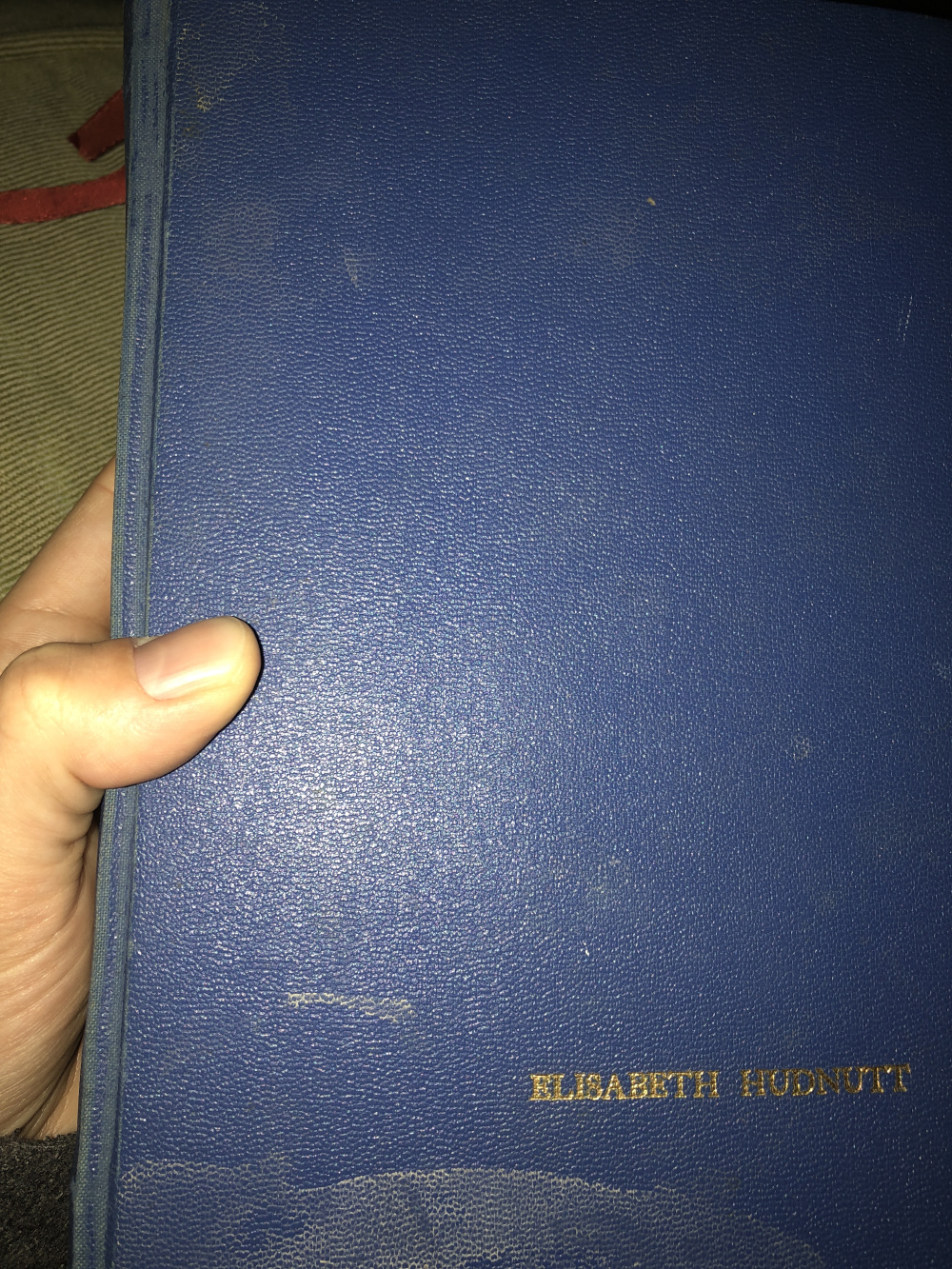

Hyenas’ Dramaan in the merry calm before the storm

Hyenas’ Dramaan in the merry calm before the storm

Colbane is in a bad place. Its city hall is repossessed by unknown faces early on and the Mayor has no solutions to his town’s plummeting fortunes. In the course of the film, Mambety spices in shots of vultures overhead and hyena’s on the outskirts painting the picture of a decaying town nearing its complete end. But at the seeming tipping point of this story, a ray of sunshine emerges as Linguere Ramatou’s (Ami Diakhate) return is announced. She left the town under controversial circumstances as a teenager but she is hailed as a returning messiah because of her riches. She has more money that the World Bank, the town crier announces to ominous effect.

Linguere and Dramaan were lovers as teenagers and Mambety pivots of this detail to perhaps give us a snapshot of politics in Africa. When the town council becomes aware of Dramaan’s history with Linguere, he is essentially made the head of the welcoming committee and christened the next mayor of the town despite being all but the village idiot. Dramaan is in the best position to beg for aid so he is the best man for the job, basically. To hell with even the minimum levels of competence and vision when you have the man who can woo the woman with the chequebook.

Linguere, if anything, is the exact opposite of Dramaan. She has this snobbishness one could liken to modern day expatriates who have no patience for antics in the homeland. Linguere is incredibly aware of not only the asininely obsequious nature of her hometown but she also banks on their overestimation of their decency. The hope and joy that greets Linguere’s arrival are replaced with sneers and contempt when she shows her hand. She wants Dramaan dead, and she wants the town play executioner in a case she passed judgement on decades ago. Dramaan is no saint, mind you. Linguere produces two men who confess to being bribed by her former lover to testify that they had sex with her so he could deny being the father of her unborn child.

My first encounter with the idea of a hyena was probably in The Lion King or maybe the “laugh like the hyena” simile. They are weird animals; not as threatening or graceful as lions but more vicious in a weasely way. In Mambety’s world, hyenas seem to represent a curse – the portion of a people that will never have it all in a painfully cynical existence. We think the people of Colbane are staring through a window to the hyena prepared to loot and plunder their morality. Then we realise they are staring into a mirror. The people also smell blood and decay and the succumb to their innate nature in Mambety’s eyes, whether it is feeding a chain of bureaucracy and corruption or hailing a coup orchestrated by western entities. Sorry again Nkrumah, and I hope Zimbabwe stay watching.

The neo-colonialism beats are clear to see and the layer one would most expect from a totem of pan-African filmmaking. Linguere has already been likened to the World Bank and her presence increases exports into the town in a manner Mambety wants us to view as disconcerting and suffocating. It starts with the bright yellow boots imported from Burkina Faso that flips Dramaan off and ushers in a sense of manic paranoia. Before we know it, a mirage of money seems to be flowing through the town; TVs, air-conditioners and fridges make their way into this rural community and just like that, we have witnessed a communist’s nightmare. Mambety’s surreal sensibilities come to the fore when we realise a vibrant full blown amusement park within the town, seemingly completing this village’s turn to the capitalist side.

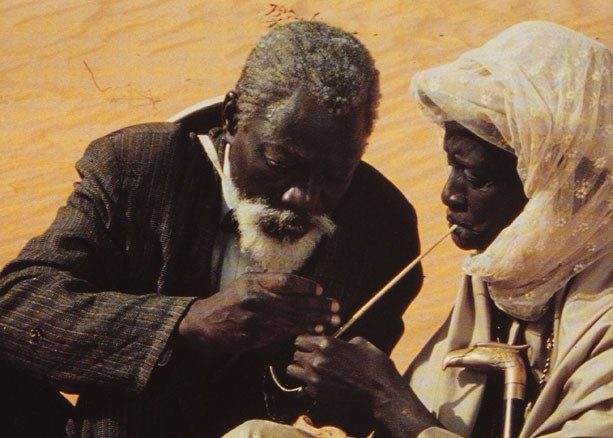

The ink is already dry for Dramaan and Linguere

The ink is already dry for Dramaan and Linguere

Shoving the misanthropic lament on our motherland aside for a bit, Hyenas is also a tale of vengeance on culture, the patriarchy and ingrained chauvinism. “Life made me a whore and now I will make the world a brothel,” is the line of this film, delivered by the stoic Linguere. She never loses sight of the big picture and Dramaan’s possible demise is almost only a means to an end. In many respects, Linguere is a broken thing. She has a gold prosthetic leg and arm and has spent her life selling her body as a prostitute. She has nothing left and is in search of her own demented balance – a balance that will be restored by stripping Colbane of its soul making nonsense of its sense of morality and justice.

Ideas reign supreme in Hyenas. The actors are seldom brought in to carry a scene, though most of them are well crafted. Linguere is afforded the best lines, laden with wit and depth, and she is able to evoke the needed empathy despite her methods. Dramaan’s arch is compelling to watch as he ironically realises that every pillar of society; family, law and religion, is made of straw. That the performances never come off as captivating or exhilarating is partly down to the very animated cadence, which I sometimes find grating and obviously dated in 2017, though it doesn’t stray far from authenticity.

Mambety’s style is more definite here. He frames some beautiful shots and crafts some truly enthralling moments in Hyenas. Consider Linguere and Dramaan overlooking the vast ocean in a call back to Touki Bouki, the girl in pink vigorously dancing against the desert landscape amid the high of Linguere’s arrival or that night scene at the train station chillingly evoking a lynching. However, Mambety’s pacing is uneven as he doesn’t seem to favour sustained moments with his characters. He also has this annoyingly short attention span, as he constantly cut back and forth between elements of unequal importance.

Hyenas remains ever poignant in its bleak, surreal and farcical splendour. The hyena in Senegalese culture represents evil and corruption. The line: “We are still Africans. We are civilized people. We won’t kill for money,” is simultaneously the funniest and saddest of the film. 20 years on from Touki Bouki, the world hasn’t changed for Mambety. 25 years on from this film, years in which Mambety has since died, his films remains a dusty crystal ball stained with tears.

–

delalibessa@yahoo.com

Rate this:Share