How did doctors understand and treat “hypochondria” in Jane Austen’s world?

While Mr. Woodhouse, as we said last week, is often described as a hypochondriac, the real hypochondriac in Emma appears to be Mrs. Churchill, Frank Churchill’s adopted mother. According to Worldwide Words, “the hypochondriac thinks he’s always ill, but the valetudinarian takes great care to ensure he never is.” Mr. Woodhouse, the valetudinarian, constantly attempts to protect his health and his family’s health, while Mrs. Churchill, the hypochondriac, claims to be ill to get what she wants.

Mrs. Churchill and Other Hypochondriacs in Austen’s NovelsMrs. Churchill never appears directly in Emma, but is offstage manipulating her adopted son Frank Churchill. (She adopted her nephew when his mother died, raising him to wealth; Jane Austen’s brother Edward Knight was similarly adopted by a wealthy relative.) Mrs. Churchill’s daily “health and spirits” control her family.

When Frank is enjoying a visit to his father and friends, she calls him back suddenly, claiming to be “far too unwell to do without him,” though she hadn’t mentioned it earlier because of “her usual unwillingness to give pain, and constant habit of never thinking of herself.” This reminds me of Mrs. Bennet in Pride and Prejudice, who complains, “People who suffer as I do from nervous complaints can have no great inclination for talking. Nobody can tell what I suffer! But it is always so. Those who do not complain are never pitied.” Mary Musgrove of Persuasion, another hypochondriac, tells her sister she wrote her a cheerful letter because “I made the best of it; I always do; but I was very far from well at the time; and I do not think I ever was so ill in my life as I have been all this morning–very unfit to be left alone, I am sure.”

All these characters use claims of ill health in an attempt to get attention, company, and their own way.

Frank Churchill is called home suddenly because Mrs. Churchill “is far too unwell to do without him.”

Frank Churchill is called home suddenly because Mrs. Churchill “is far too unwell to do without him.”

Mrs. Churchill’s claim to ill health is belied by her exertions when she wants to do something. She is too ill to walk without help, yet when she decides her home is too cold, she travels across country with few rests. Likewise Mary Musgrove is able to get up and be active once she has company, and Mrs. Bennet recovers from her ill health as soon as she hears her daughter Lydia is to be married.

Their illnesses are ascribed to nerves. Mrs. Churchill has a “wilful or nervous part of her disorder.” She can’t tolerate the noise of London because “her nerves were under continual irritation and suffering.” Her health is “liable to . . . sudden variation.” When Frank wanted to go to Highbury, Mrs. Churchill suddenly had “a nervous seizure, which . . . lasted some hours.”

Her death, though, surprises everyone. “A sudden seizure of a different nature from any thing foreboded by her general state, had carried her off after a short struggle.” Suddenly everyone believes that she really had been ill: “The event acquitted her of all the fancifulness, and all the selfishness of imaginary complaints.” Even though the seizure that killed her seems to be quite unconnected to the health issues she had always complained of, suddenly she is justified in all her complaining and manipulation. They forget that everyone dies, eventually, of something! Perhaps she did have an underlying illness that led to her death, perhaps her constant fretting made her really ill, or perhaps she caught a sudden illness and died of it. It is clear, however, that in her hypochondria or other illness she made everyone else miserable. (Totally the opposite, by the way, of Anne Elliot’s friend Mrs. Smith in Persuasion, who is truly ill but still cheerful and encouraging to all around her!)

Frank and Jane Fairfax quarrel because of the difficulties of keeping their engagement secret from the imperious Mrs. Churchill; her death frees them to marry.

Humours

Frank and Jane Fairfax quarrel because of the difficulties of keeping their engagement secret from the imperious Mrs. Churchill; her death frees them to marry.

Humours

Mrs. Churchill is always “ill-humoured.” “Humour” was a medical term. (In America we write “humor,” thanks to Noah Webster who simplified American spelling!) The four humours in each person had to be balanced, or the person would get sick. “Ill humour” meant that Mrs. Churchill’s humours were unbalanced, causing her to be grouchy.

The humours were considered hot or cold, wet or dry. Foods, drinks, and other remedies were also considered hot or cold (not relating to their actual temperature), wet or dry, so they could be used to balance out the internal humours, as could bleeding (reducing the blood). In Mansfield Park, when Fanny Price gets overheated she drinks a glass of wine, which was supposed to be cooling. Emotional temperaments such as “sanguine” or “melancholy” were from a predominance of one of the humours.

The humours were: (Listed as: Humour, characteristics, related body part, Emotional temperament)

- Blood, hot and wet, the liver, Sanguine

- Phlegm, cold and wet, brain and lungs, Phlegmatic

- Yellow bile, hot and dry, gall bladder, Choleric

- Black bile, cold and dry, spleen, Melancholic; this was the humour that was unbalanced in hypochondria.

Hypochondria was a recognized medical condition, a nervous disorder. It was related to “melancholy” or depression (an excess of “black bile”). “Hypochondria” comes from a Greek word meaning “under the ribs”; it was thought to originate in organs located there such as the liver, gall bladder, and spleen. Let’s examine what three doctors of Austen’s era taught about hypochondria.

Dr. Hill in Hypochondriasis, A Practical Treatise (1764) called it a “real, and a sad disease: an obstruction of the spleen by thickened and distempered blood; extending itself often to the liver, and other parts” (3). Bad circulation was believed to cause a person to lose their cheerfulness and peace of mind. Because the problem was in the spleen, Hill recommended a tincture of spleenwort, a fern believed to clear the spleen (36 ff).

Hypochondria began with low spirits and energy, not enjoying amusements, thinking too much about trifling subjects. It progressed to wild thoughts, low appetite, tightness of breath, constipation, and many other physical symptoms (12 ff). Possible causes included fever, marshy soil (remember Mr. Woodhouse’s fear of dampness?), grief, love, too much study at night, too much exercise, but most often, “indolence and inactivity” (20 ff). Mary Musgrove’s hypochondria was clearly from inactivity: having nothing to do!

Mary Musgrove fancies herself ill whenever she feels neglected.

Mary Musgrove fancies herself ill whenever she feels neglected.

Dr. Reid published Essays on Hypochondriasis in 1821. Rather than the spleen, he believed that hypochondria originated in the mind, as we would say today. He emphasizes that it is still quite real, and “No one was ever laughed or scolded out of hypochondriasis” (9). “Sufferings which arise from no palpable or assignable cause, are not less real or pitiable on that account” (11).

Dr. Cullen, first physician to his Majesty in Scotland, in 1783 included hypochondria under “Diseases consisting in a Weakness or Loss of Motion.” He says people call it “Vapours, or Low Spirits.” According to Dr. Cullen, the hypochondriac fears the worst and pays attention to every small change in health, thinking it might lead to danger or death. He or she obstinately believes “all these feelings and fears” (58-9). Hypochondria is found in melancholic temperaments and increases with age. He credits its prevalence to wealth, idleness, and empty amusements, perhaps some of Mrs. Churchill’s problems.

Treatments for HypochondriaDr. Hill prescribes good air (not too hot or cold, no sudden drafts), regular exercise, visits with friends, and avoiding all excesses including excessive food and drink. He highly recommends that the hypochondriac study nature (plants, insects, etc.), to get outside and focus his mind on “the goodness of his God” (25 ff).

Dr. Reid recommends “cheerfulness, and even hilarity” (23) to improve the circulation, and looking on the bright side of whatever happens. “A person who has been brought up in the habit of doing every thing he pleases, will at length become incapable of being pleased with any thing” (25). This might describe Mrs. Churchill, obviously brought up in wealth and pleasure and now dissatisfied and restless.

Dr. Cullen mentions drinking mineral waters, such as those at Bath, but ascribes its success to “the amusement and exercise usually accompanying the use of these waters, rather than to the tonic power of the small quantity of iron which they contain” (64-5). Warm bathing (such as at Bath) may be very helpful, as well as drinking tea and coffee. He prescribes distraction as the best cure. Exercise, unstressful work, sports, hunting, and social gatherings may distract the hypochondriac from his worries.

Hypochondriacs in Sanditon and in Jane Austen’s LifeCullen says hypochondriacs often change doctors, as Mrs. Churchill does in Emma, traveling to another town to try a new doctor. Mr. Woodhouse, of course, was quite satisfied with Mr. Perry, who always confirmed his own opinions.

Placebos can be helpful, according to Dr. Cullen, since hypochondriacs, “anxious for relief, are fond of medicine, and, though often disappointed, will still take every new drug that can be proposed to them” (66). The classic hypochondriacs in Jane Austen’s final, uncompleted novel, Sanditon, have tried a series of doctors and now treat themselves with crazy remedies to cure nonexistent health problems and make themselves feel important.

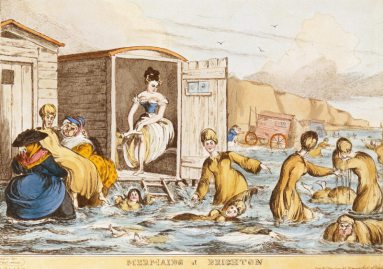

Dr. Reid prescribes sea air for hypochondriacs. In Sanditon Austen laughs at those who believed the sea was the cure for everything; her Mr. Parker believes sea air and sea bathing are “anti-spasmodic, anti-pulmonary, anti-septic, anti-billious and anti-rheumatic.” Mr. Woodhouse’s daughter Isabella, who takes her daughter to the sea to heal her sore throat, might have agreed with Mr. Parker, though Mr. Woodhouse says sea air almost killed him once!

“A Little Sea-Bathing would set me up forever,” says Mrs. Bennet. Sea-bathing was recommended for hypochondria and many other ailments.

“A Little Sea-Bathing would set me up forever,” says Mrs. Bennet. Sea-bathing was recommended for hypochondria and many other ailments.

Austen’s own mother was apparently a hypochondriac, complaining of a variety of diseases even when she was healthy; she lived a long life in spite of her complaints. Jane knew other hypochondriacs as well; she describes an acquaintance in a letter on September 25, 1813 as “a poor Honey—the sort of woman who gives me the idea of being determined never to be well and who likes her spasms and nervousness, and the consequence they give her, better than anything else.”

Austen’s hypochondriac characters are selfish and bored, imagining themselves ill to receive attention and manipulate those around them. However, their ailments feel real to them. Doctors in Austen’s England knew that the mind can affect the body. It’s not helpful to tell someone their ailments are all in the mind, whether they are or not.

Do you ever have times when you feel that you or someone you love is too focused on health? Some of the above medical advice might be useful: try distractions, exercise, outdoor activities, enjoying nature, time with friends, and, especially, worthwhile work!

In the next two weeks we’ll be looking at another health issue, gout, how it was treated, and whether the waters of Bath actually helped.

Sources“Hypochondria” (etymology)

Lane, Maggie. Growing Older with Jane Austen. London: Robert Hale, 2014. “The Dangerous Indulgence of Illness,” chapter 11.

Harris, Jocelyn. “Jane Austen’s Satire on Hypochondria.” Nov. 21, 2016.

HumoursKramer, Kyra Cornelius. “Regency Medicine: Betwixt and Between.” March 4, 2017.

Emsley, Sarah. “Why Mr. Woodhouse Takes Care About What His Guests Eat.” Jan. 8, 2016.

Medical Texts on HypochondriaHill, J., M.D. Hypochondriasis: A Practical Treatise on the Nature and Cure of that Disorder; Commonly called the Hyp and Hypo. London: Printed for the Author, 1767.

Reid, John, M.D. Essays on Hypochondriasis, and Other Nervous Affections. London: Longman, 1821. Second edition, originally published some years earlier.

Cullen, William. First Lines of the Practice of Physic. [Physic=Medicine] Part 2. Edinburgh: Elliot, 1783.

Advertisements Share this: