What follows are six contributions (divided into two posts) by scholars and activists who responded to a call circulated via the ENTITLE network in November 2017, shortly after James O’Connor’s death. Our intent was to solicit personal reflections and memories on how O’Connor had influenced people who encountered his work in different ways and across three different generations.

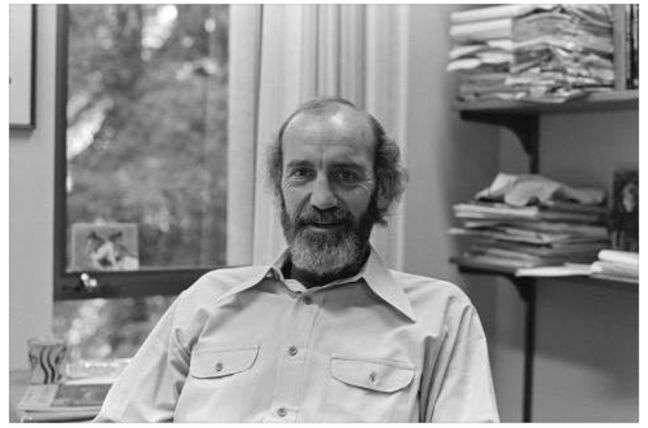

James O’Connor in 1978 (photo courtesy of the UC-Santa Cruz Digital Collections)

James O’Connor in 1978 (photo courtesy of the UC-Santa Cruz Digital Collections)

Joan Martínez Alier

Before I met Jim O’Connor in person, sometime in early 1989 in the beautiful campus of Santa Cruz of the University of California, I had read already his anticipatory book The Fiscal Crisis of the State of 1973 and the introduction that he wrote to the first issue of Capitalism, Nature, Socialism in 1988 on the “second contradiction of capitalism”. He edited this journal with Barbara Laurence for some years, until bad health made him to stop. The journal continues to this day, and from the beginning it was a sister journal to Ecología Política (published in Barcelona by Editorial Icaria and its director Anna Monjo), Ecologie Politique (issued in France by Jean-Paul Deléage), and Capitalismo Natura Socialismo (the Italian journal edited by Giovanna Ricoveri). These alliances have endured until today.

For some years we had a close relationship. In the first issues of Ecologia Política we translated many articles from CNS, although I had a pro-peasant, pro-Narodnik bias that amused him a little. We never had a political disagreement, and whatever I would include in Ecologia Política he would agree with, attributing any surprising material to my anarchist inclinations to be expected from somebody from Barcelona (meaning the Barcelona of 1936). He came to Barcelona for the launching of Ecología Política in 1991. We organized debates on the “second contradiction of capitalism” in Ecologia Política, translated from CNS but also with original articles. I believed and still believe that the “second contradiction” was a brilliant concept that helped to make sense of the myriad movements for environmental justice around the world.

The word “eco-socialism” (misappropriated by a post-communist party in Catalonia) was introduced in Barcelona in this launching meeting of Ecologia Política in 1991 organized also by the environmental sociologist and professor at the UAB, Louis Lemkow. We were all eco-socialists, and still are. But in my case I was socialist in the sense of the First International, with anarchists, Russian pro-peasant populists, and Marxists trying to live together – which unfortunately proved impossible in 1871. Later, the Marxists split into two main currents, the “German” Social Democracy and after 1917 the Leninists, both equally oblivious (in my view) of ecological issues.”Eco-socialism” had to go back to 1871, adding ecologism and feminism to socialism, and looking at the whole world and not only to Europe. We broadly coincided with Jim O’Connor in this view. The main article in the first issue of Ecologia Politica was not by Jim O’Connor or by myself but by Victor Toledo, the Mexican ecologist and pro-peasant eco-socialist. I also introduced in Ecologia Política and CNS the knowledge I was gaining at the time of the “environmentalism of the poor” in India and Latin America.

In his book of 1973, The Fiscal Crisis of the State, which anticipated the crisis of Keynesian social-democratic capitalism of 1975 and the rise of neoliberalism with Reagan and Thatcher, James O’Connor had argued that the capitalist state had to fulfill two fundamental functions, namely accumulation and legitimization. To promote profitable private capital accumulation, the state was required to increase taxes in order to finance the welfare state, increase social security, lower the reproduction costs of labour, and thereby increase the rate of profit of capital, at the same time maintaining social harmony through social expenses, for instance on unemployment and health benefits. All this became contradictory. It implied increasing taxes, and there would be a capitalist rebellion against taxation, as indeed it started in California. The state would enter into a fiscal crisis. The budget deficits became associated with the idea that government had become overloaded, that full employment was no longer an objective of macroeconomic policy, that trade unions were too powerful. The neoliberals were to preach a roll back of the state.

In 1988, Jim O’Connor came out with a resounding new thesis in the introduction to the journal Capitalism, Nature Socialism. The issue was not only that investment in the search of profits increased productive capacity while exploitation of labour decreased the buying power of the masses. This was the first contradiction of capitalism. There was a second contradiction. The capitalist industrial economy undermined its own conditions of production (he should have said, in my view, the conditions of existence or the conditions of livelihood, and not only the conditions of production).

There was exhaustion of natural resources, there was introduction of dangerous technology like nuclear power, there were new forms of pollution, and capitalism had not the means to correct such damages. A new type of social movements were arising, and the main actors were not the working class but an assortment of social groups, often led by women, often composed of ethnic minorities. The fact that the “environmental justice” movement had arisen in the US in 1982 inside the Civil Rights movement, reinforced Jim O’Connor’s thesis, and his journal published several articles on this movement that fought against “environmental racism”.

To me Jim O’Connor (and before him, in 1986, Enrique Leff’s “Ecologia y Capital” which I persuaded Jim to have translated into English) were main sources of inspiration for the work I have done and still do (being ten years younger than Jim) on the global movement for environmental justice and the EJAtlas. He knew that I was grateful to him.

Stefania Barca

I first came across the work of James O’Connor through the Italian magazine Ecologia Politica – CNS at the end of the 1990s; but it was during my first study trip in the US, in 1999, that I encountered his work more directly, when I found his Natural Causes on the desk of environmental historian Donald Worster – whom I was visiting.

The entire first part of the book (five chapters) was devoted to environmental history. It was a revelation: O’Connor had, at once, revised historical materialism and theorized labour not as the enemy of nature, but as a partner in a common history of capitalist exploitation, claiming that “the more that (human modified) nature is seen as the history of labour, property, exploitation, and social struggle, the greater will be the chances of a sustainable, equitable, and socially just future.”. That answered my questions – even those I did not know I had – on how class mattered to ecology, and vice versa.

To me, O’Connor’s call for an ecological Marxism sounded like a fresh and liberating vision of environmentalism, once and for all freed from – as he wrote in his ‘second contradiction’ article – “bourgeois naturalism, neo-Malthusianism, Club of Rome technocratism, romantic deep ecologism, and United Nations one-worldism”. This vision introduced me to what I then came to know as Marxist political ecology.

Only much later did I pay attention to O’Connor’s reference to Polanyi, in his article on the second contradiction, a reference which informs his idea of eco-Marxism as a struggle for the defence of the conditions for human reproduction through broad social alliances beyond the political subjectivity of workers’ movements, and embracing a multitude of subjectivities and struggles (feminist, anticolonial, anti-globalization etc).

I found this approach was shared by two of my most favourite authors: the British socialist Raymond Williams, who advocated the overcoming of divisions between labour and environmental movements on the basis of a common anti-capitalist struggle for the defence of ‘livelihood’; and, more recently, Nancy Fraser, who refers to both Polanyi and O’Connor in pointing to what she calls ‘boundary struggles’, i.e. those that link the point of production with struggles around social reproduction, ecology, imperialism and state power.

O’Connor’s second contradiction thesis still inspires me, today, as a call for developing an ecological class-consciousness, capable of appropriating the ecological as a multi-layered terrain of struggle for emancipation, rejecting top-down solutions to the climate crisis and rethinking the global working class (intended as the unity of production and reproduction labour) as an agent of ecological revolution.

Roberto Sciarelli

I learned about James O’Connor during the spring of 2013, while I was exploring the bookshelves of the A Sud association, in which I was conducting my first working experience. My role there was to describe instances of ecological mobilizations in Italy, but at the same time I was desperately searching for a theoretical framework for my bachelor thesis. The idea of my dissertation was to compare Marxist theory of class struggle with political ecology in the interpretation of environmental conflicts.

Of course, my project was just as ridiculously ambitious as only a bachelor thesis can be, and I did not even know about the existence of Marxist political ecology, but encountering the first issues of Capitalism, nature, socialism changed the situation a lot. The Theoretical introduction to ecological Marxism amazed me for how rigorous, sensible and coherent it was, and for the deep explanation it provided for the matters I was (and I am still) investigating.

I remember that my co-supervisor was not particularly happy about the eco-Marxist turn of my thesis, but for me it was clear that O’Connor had provided a precious frame of reference for my research. I focused on the definition of conditions of production, on the distinctions between them, on how the role of the state in managing them can shape contemporary political mobilizations.

I was especially interested in understanding the part played by social movements in triggering crises of costs, that is, the second contradiction of capitalism. The more I compared these concepts with the reality of the environmental conflicts I was observing for my internship work, the more I was convinced of their political relevance.

The main objective of James O’Connor was to provide a useful theory which could build bridges and form alliances between workers’, feminist, environmentalist, communitarian and urban movements in the age of the ecological crisis. The political struggles of today and the knowledge produced by them are showing that it was indeed the right direction to follow.

Concepts like “bodily-territories”, developed by Ni Una Menos; the combination of urban and indigenous mobilizations against the new phase of violent extractivism; the wave of ecological militancy in the de-industrialized landscapes of Southern Europe; the strength showed by the communal, neo-municipalist and democratic confederalist struggles from Latin America to the Mediterranean Sea and Mashriq, which are breaking the hold of states and capital over resources, communities and peoples… These are some of the many instances which give testimony of the acuteness of O’Connor’s views and of the importance of the debates he stimulated.

Share this: