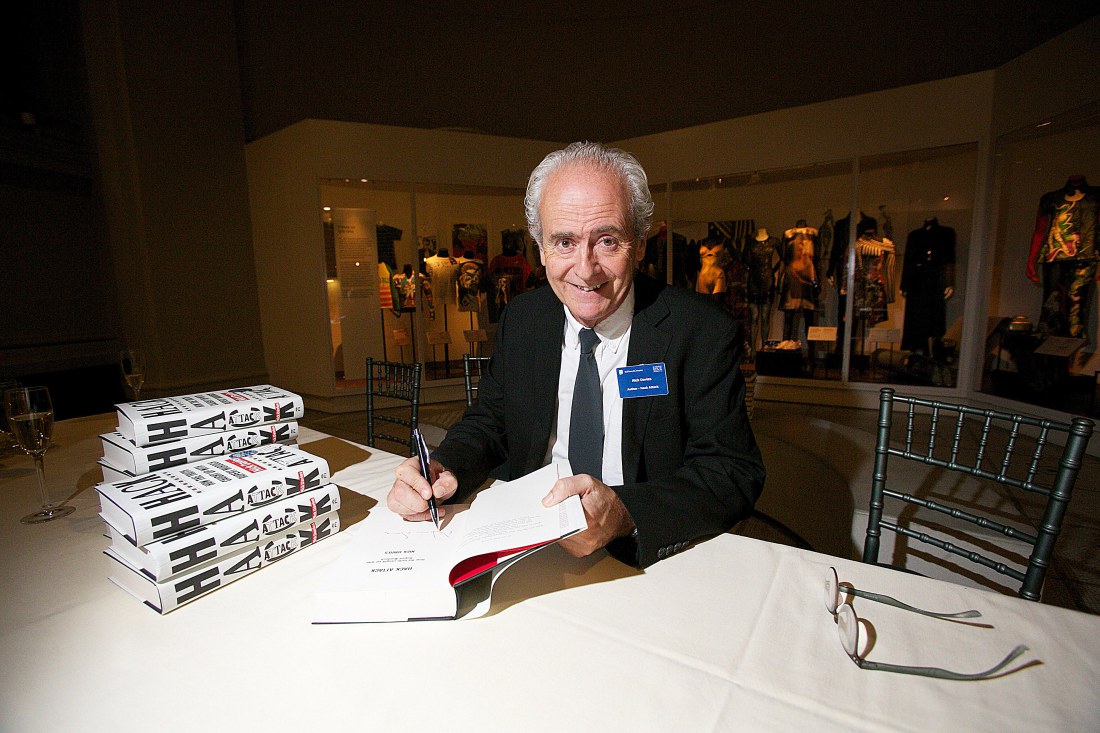

When it comes to investigate journalism, there are fewer names more well-known that Nick Davies. Working extensively with the Guardian, it was Nick who set in motion the partnership between the paper and Wikileaks, which would eventually lead to the publication of the Iraq War Logs in October 2010. He also was instrumental in uncovering the News International phone hacking scandal in July 2011. His involvement in exposing some of the most alarming abuses of power in recent times gives him a healthy distrust of authority – but his passion for the truth, and the integrity of both media and political practice, is evident.

–

GP: Your work, particularly on uncovering the Murdoch phone-hacking scandal, could be described as a key instrument of holding power, and powerful organisations, to account. You yourself have described it as a way to “expose the world of power”. Do you see journalism as being the most effective way of doing this?

ND: I think that the ability of journalism to hold power to account – i.e. the ability of words to effect change – has declined sharply, primarily as a result of two structural problems created by the Internet. First, there are now so many damn words out there that it is correspondingly more difficult for any one set of words to be heard. It’s like wandering around on a football ground without a microphone in a stadium full of people all shouting. Second, even if one set of words does manage to break through the cacophony, they run into a secondary problem, that the public domain now is so heavily infected with falsehood and unreason that the words are far less likely than in earlier eras to effect change of any appropriate kind. I’m not pretending that there ever was a golden age when all words were heard or when all public/political reaction was logical and reliable. But I think that recently we’ve crossed the line into an age of information chaos. And that makes it much more difficult to engage in journalism as any kind of activism. Not impossible, but much more difficult. I became a journalist because of Watergate – words unseated the most powerful politician in the world. It’ll be very interesting to see how things unfold with press coverage of Trump and the Russians.

GP: You have written extensively on falsehood in the media – do you regard the rise of the concept of ‘fake news’ as a substantive threat to your industry? How do you see it adapting to the phenomenon?

ND: I don’t mean to sound obsessive, but the threat to my industry is not from fake news, it’s from the Internet, specifically from Google and Facebook – two of the greediest and most power-hungry creatures ever to prey on the inhabitants of this planet. Where journalism is concerned, they have spent years distributing our work without paying for it, so that our income from readers has gone into steep decline. In the last few years, they have become far more efficient at exploiting the user data which they harvest, in order to sell advertising, so that our other source of income – carrying advertisements – has also gone into steep decline. All across the developed world, news organisations have had their business model broken, so they have fewer staff and fewer resources and therefore less chance of finding stories, checking facts, doing their job. It is worth adding that the threat from Google and Facebook goes well beyond the damage they are inflicting on journalism. They are stealing the Internet – now taking something like 90% of new online advertising. They are invading our privacy on a scale that must make the mouths of spies water with envy. They are exploiting our personal data for their greed, often without our knowledge or consent. And they are creating a global information sewer, simultaneously spreading falsehood while undermining the one profession whose job is to spread truth. My small and ineffective protest: I don’t use either of them. Go on – kill your Facebook account, and use Duckduckgo as a search engine which doesn’t track you.

GP: In today’s context of widespread (often deliberate) misinformation, how do you think the roles of both whistle-blowers and state secrecy have been affected? Do you think either group now has a greater responsibility to make known the ‘truth’?

ND: Whistleblowers have always been important, to engage in the legitimate exposure of corporations, governments, powerful individuals who abuse their power and who try to keep that abuse secret. I don’t think that there is anything new about their importance or about the level of their importance. What is new, of course, is that the electronic storage of information makes it possible for a whistleblower to disclose far more than was viable in the old days of hard-copy records. Which is why the leaks have got bigger and bigger – Manning/Wikileaks; Edward Snowden; Panama Papers. Enormous in scale. They’d have needed a truck to extract that amount of information in pre-digital days.

GP: Finally, what would you say is the best lesson you have learnt in your many years as an investigative journalist? This can be specifically regarding journalism or in a more general sense.

ND: Maybe what I’ve learned is always to be aware of the difference between those who belong to the power elite and the rest of humankind. Those in the power elite, in my experience, have an overwhelming tendency to be dishonest and ruthless and selfish: there are some exceptions to this, but there are a lot of really horrible people running our governments and corporations (and some of our newspapers). I spent a lot of time trying to expose what they were up to. So it’s easy to fall into a fundamental error of thinking that their behaviour is a reflection of our species in general. But more and more, as I get old and reflect on my experience as a reporter, and as I travel around the world encountering strangers, I notice how ordinary people are fundamentally honest and decent and kind. OK, there are exceptions there too, but the trend is strong. I came of age in the late 1960s, and, among other reasons for looking back with pleasure on the amazing counter-culture of that time, I appreciate more than ever one of the slogans which was sung and shouted and painted on the subway walls: ‘Power to the people!’ If only….

Interview conducted on 01/11/17.

Image @Wikimedia Commons

Share this: