In 1992, id Software released Wolfenstein 3D, which is popularly considered the original first-person shooter. This isn’t quite true, as programmer John Carmack had been experimenting with 3D game engines before then to conceive prototypes such as Hovertank 3D and Catacomb 3-D, but it wasn’t until the debut of this game that the first-person shooter became established in the public eye. This new movement would gain even more momentum with the release of Doom the following year. With its gruesome content and satanic imagery Doom met with no shortage of controversy. Many activists believed it would have an adverse effect on their children, and mold them into violent criminals. Nonetheless, it was vindicated by historians, and is considered one of the defining PC games of the early nineties with a legacy that endures to this day.

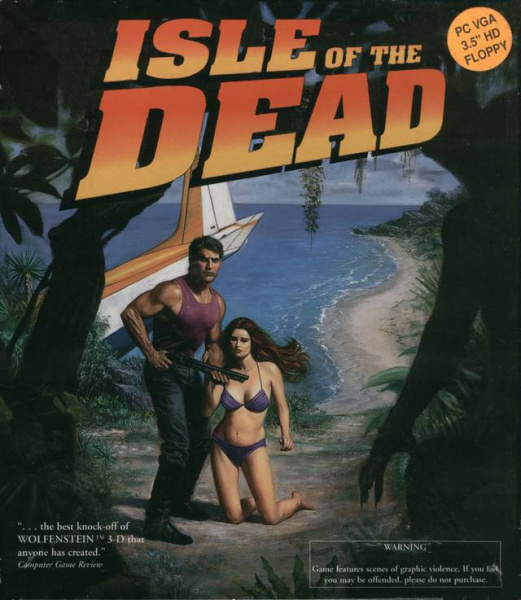

As both games were selling copies by the thousands, one group of developers saw potential in this new, developing genre. They called their venture Rainmaker Software, and their first game, Isle of the Dead, was released in December of 1993 – around the same time as Doom. Needless to say, it turned out to be a case of mismatched opponents, and the effort of this new company quickly faded away. While PC gaming fans were busy with Doom, what did they choose to pass up in Isle of the Dead?

Analyzing the ExperienceThe protagonist of this story is Jake Dunbar. He is the sole survivor of a plane crash, and has found himself marooned on a mysterious tropical island. The locale is invested with zombies, and his goal is simple: he must escape the island alive.

It’s clear upon starting the game that it took many cues from Wolfenstein 3D with its universally flat surfaces and textured blocks acting as walls. The first thing you will do upon starting a new game is investigating the plane’s crash site.

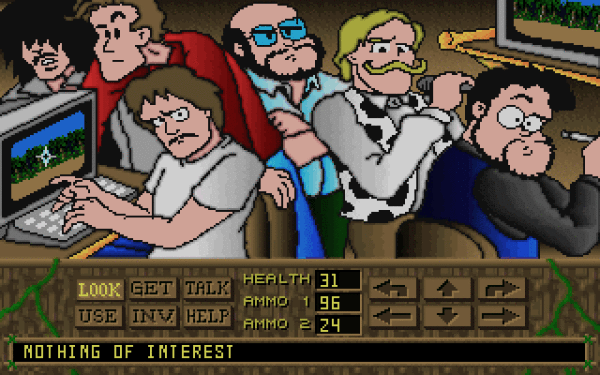

From here, Isle of the Dead becomes an adventure game that is also played from Jake’s perspective. You can use the navigational buttons to turn, advance, or backtrack. The six commands you can use to interact with your surroundings are: “Look,” “Get,” “Talk,” “Use,” “Inv.,” and “Help”. “Look” will give you a short description of the set piece you click on. “Get” adds an obtainable item to your inventory. “Talk” allows you to converse with an onscreen character. By selecting “Use,” you can interact with an object, though if you can obtain it, you will be prompted to do so instead. “Inv.” takes you to the inventory screen where you can make use and keep in track of your possessions. Lastly, “Help” brings up an instructional page.

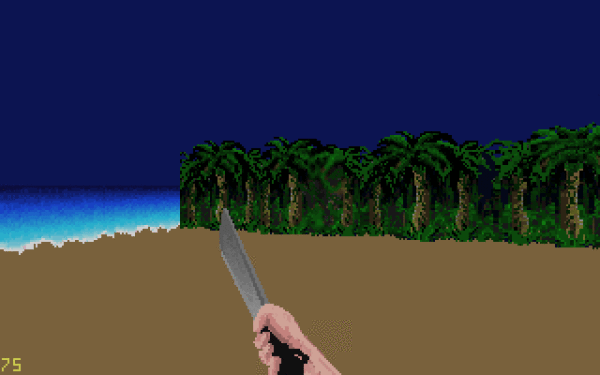

Upon leaving, you will likely wander around the small area of beach you’ve found yourself on for several minutes only to realize there are no obvious exits. They do indeed exist, but you will need to use an item to find them. Within the wreckage, you will find what you need: a machete, which also happens to be your first weapon. Using the bladed weapon, you can carve through the island’s undergrowth to move further inland or explore the rest of the beach. One such passageway can be seen in the following screenshot.

If you’re having trouble seeing it, the tile I’m referring to has the slightly overgrowing vines. Though it may seem obvious when you know about it, when playing the game for the first time, you would be forgiven for assuming it’s a piece of the background. In the event that you’re questioning whether or not this was a minor oversight in an otherwise fine game, allow me to assure you this is far from an isolated incident. In fact, this sets the tone for the kinds of design decisions you will have to deal with for the rest of the game.

Attempting to go inland is futile without a firearm; the machete is a pitiful means of defense against the hordes of zombies plaguing the area. By exploring the beach further, you will happen upon a cave. In here is exactly what one would need in a first-person shooter: a rifle.

Don’t be in too much of a hurry to get it, however, for there is a trip wire blocking it. Setting it off will activate the trap, exploding the protagonist with a grenade. After snipping the wire and procuring the rifle, you can equip it when you’re outside. Humbled by a defeat at the hands of the undead, the eager player will likely want another attempt at fighting the zombies. After lining one up in their sights, they fire it once.

Unfortunately, the firearm was in decidedly poor condition. Having adventure game elements, one might find it wise to examine items before using them. It could even tell you what you should have done.

Looking at the rifle merely informs you that it is, in fact, old. Evidently, that whoever tries to use it will have their face blown off was deemed an unnecessary detail by the staff. What you need to do is examine the cave further and pick up a can of oil and a rag. You can use them to clean the rifle so that it is safe to use. This is one of those incredible puzzles that fails in every conceivable way. There is no way anyone attempting to play this game blind could possibly avoid dying in this manner, and the text doesn’t even have the courtesy to hint towards the correct course of action.

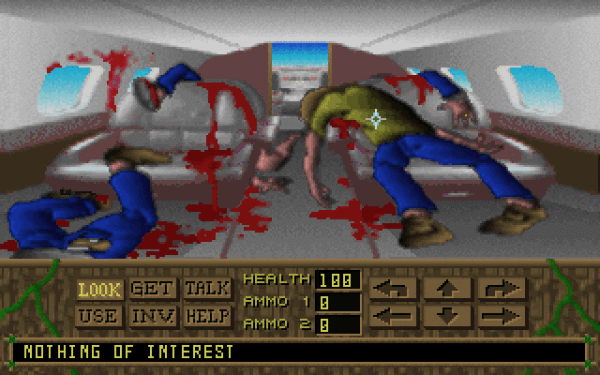

For that matter, one of the worst aspects of Isle of the Dead is the extremely small amount of interactivity you can have with the environment. Whether information is dispensed by an omniscient narrator or conveyed through the protagonist’s subjective thoughts, one of the greatest appeals of adventure games lies in examining one’s surrounding and reading the flavor text. To give you an idea of how detached Isle of the Dead is from this simple concept, it claims a corpse in a plane crash is “nothing of interest”.

For the most part, the only things you can interact with are required in some way to complete the game. If you do examine points of interest, you get a single, terse line of text which rarely reveals any information that couldn’t be observed with your own eyes. Although the game strived to have a distinctive art style – almost resembling an animated B-movie – that personality doesn’t carry over into the gameplay, and is thus bland and flavorless.

After establishing that Isle of the Dead is a woefully subpar adventure game, one might be questioning if it fares any better as a first-person shooter. The answer to that inquiry is a resounding no. In fairness, some of this has to do with the fact that it has aged poorly in terms of gameplay. Doom proved to be an improvement over its spiritual predecessor, Wolfenstein 3D, so any title imitating the latter’s mold is going to feel outdated when a superior alternative exists in the market at the same time. However, the biggest difference between id’s early-nineties canon and Isle of the Dead is that, primitive by today’s standards though Wolfenstein 3D may be, it’s still entirely playable. The same couldn’t be said of Rainmaker’s effort.

To begin with, opening new areas requires the machete. If you’re too close to the wall, you will enter the area with the machete equipped. Given that it’s the worst weapon in the game and zombies swarm you as soon as you arrive, one can see why this would pose a problem. In most first-person shooters, walking into an item is enough to collect it. In Isle of the Dead, you need to be in the exact right spot and hit the “G” key or it doesn’t count. Sadly, these are the game’s lesser grievances.

I’m fairly confident anyone looking at this screenshot can discern for themselves a number of problems right off the bat. The most obvious one would be the interface. The bottom-left number represents your health while its opposite indicates the ammunition for your currently equipped weapon. The digits are so small that keeping in track of your status can be next to impossible when facing multiple enemies at once. Not only that, but there is very little feedback in combat. The only indication you’re being damaged is a thumping sound that’s difficult to hear when firing a weapon. The screen doesn’t flash, nor does your character grunt when you’re hit. This becomes a problem when enemies sneak up on you, as they can drain your health in seconds, giving off the illusion that you died for no reason.

Furthermore, every time you die, the game’s antagonist, a mad scientist, immediately laughs in a stereotypical villain fashion. It is precisely as annoying as it sounds. He even shows up if you have the temerity to quit the game, which is incidentally your smartest course of action. When you do, Jake commits suicide in a ridiculously gratuitous animated sequence wherein he places a shotgun below his chin and pulls the trigger. Calling it tasteless is a dire understatement.

What makes the scientist’s insipid cackling especially irritating are the numerous ways in which you can die instantly. You might notice a brown circle next to a set of palm trees. It’s a snare, and stepping in it will spell your doom. When you’re running from one end a map to another trying to shake off zombies, it’s very easy to run into one by mistake. It was common in many classic adventure games for the player character to be unceremoniously killed through convoluted methods. In one King’s Quest installment, you could die trying to open a seemingly ordinary brass bottle. What Rainmaker inadvertently demonstrated was how terrible that design choice becomes when transplanted into other genres.

It doesn’t help that the zombies themselves are pretty unimpressive. They come in several varieties, but they all employ the same tactics of walking up and hitting you. None of the enemies are equipped with firearms; they can only damage you when you’re within their reach. Needless to say, this gets monotonous very quickly. Most of the challenge doesn’t lie with fighting zombies, but rather finding the safest area of the map so you can launch your attack. The only way you can determine that is through trial and error.

Whenever a game encourages exploration, a basic requirement is that the process isn’t tedious in any way. Once again, Rainmaker utterly fails this grasp this concept; every time you leave a map, the zombies respawn. Normally, this wouldn’t be so bad, except the exits and entrances don’t seem to work when you’re being pursued. It does make a little sense; if you could simply run from room to room, you would have little reason to ever shoot the zombies. In practice, all this does is waste your resources every time you go the wrong way.

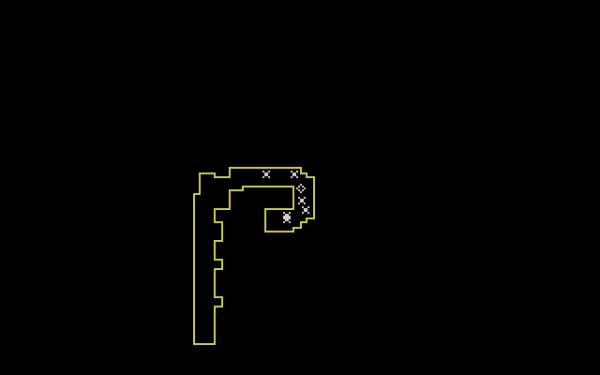

Exacerbating matters are the graphics. Visuals are not the sole factor in appraising a work, but with Isle of the Dead, all of the areas look virtually identical, so unless you draw your own map, most of the experience is going to entail entering an area, killing all of the zombies, and then reloading an earlier save file in the event you hit a dead-end. For those who think having a notepad ready is unreasonable and are asking whether or not the game provides its own map, I can tell you that it does.

It’s completely useless though; it only shows a vague outline of the immediate area. It doesn’t add up as you unlock new areas, nor does it label the exits.

Even after detailing all of these fatal flaws, one manages to outdo all of them – that would be how easy it is to render the game unwinnable. Within the wreckage, you better make sure to take all of the items. Among them is a phrase book you can use to communicate with the natives. If you neglected to pick it up, you’re permanently stuck and have to restart the game from the beginning. This is because you can’t enter the wreckage after enough time has passed. This would be a cruel trick in any other game; in Isle of the Dead, it’s below par for the course, if anything. At least you have to enter the plane in order to get the machete, which you need to leave the beach at all.

Instead, the worst dead-end situations tend lie within the game’s end sequences. After conversing with a native village chief, you are given the task of rescuing his daughter and defeating the scientist who created all of the abominations running around. After a lot of aimless wandering, you’ll find the entrance to his compound. It’s secured with a padlock, and if you try to cut it, you will get electrocuted for your troubles. What you have to do is go to a completely different area and shoot a generator with the rifle. The shotgun, the other weapon you can obtain, has an insufficient range, so only after cleaning the rifle can you progress.

After infiltrating the compound, you rescue the chief’s daughter from the scientist. He confronts you on the way out, and despite being the toughest enemy in the game, the only thing distinguishing him from his zombies is his higher amount of health. As long as you have a good weapon, he won’t be able to move as you shoot him. Once he’s dead, you can leave through the back door. Here, you find a plane, but the chief’s daughter is afraid of heights, so instead, you will have to use a life raft located inside the aircraft.

Suddenly, as you make your escape, she acts strangely and attacks you. The doctor injected her with a serum that turns her into a monster, and if you take too long to finish the game, you will die. The only indication anything is amiss is that looking at the woman will reveal she looks a little sick. The solution is to get items found in various parts of the island, including a flower and a jewel, which you can mix to create an antidote. Because the girl’s turning works on a timer, this is only realistically possible if you got the items beforehand.

If you’ve read up until this point and are wondering if any of these seemingly random actions makes more sense in context, I will just say right now that they do not. Very little of what I’ve described is alluded to in the game. I’m left to believe the few people who played and completed this game back when it was released probably exhausted every single possibility until they drummed up the answers by accident. I can understand doing this when you’re completely stumped, but in such cases, what needed to have been done should be obvious in hindsight. With Isle of the Dead, not only do many of the solutions make no sense, the game doesn’t even sufficiently explain why they work. This is what sinks this game to a level where “bottom of the barrel” would be a major step up.

Isle of the Dead is a chaotic mess where things happen for no reason, you die because you went the wrong way, and the developers gleefully break their own rules just to spite the player. I’m not exaggerating when I say the most fun I had with the game was when I deleted it from my computer’s hard drive.

Spoiler alert – there’s no sequel, so it is indeed the end.

Drawing a ConclusionPros:

|

Cons:

|

The era of gaming that could truly be considered the medium’s golden age became a hotly debated topic once its first adopters matured into adulthood. Though there will probably never be a definitive consensus, one major advantage the nineties has from a historical standpoint is its sheer volume of classic, defining games coupled with the fact that, for want of a globalized information network, the worst of the worst tended to fall into obscurity – only high-profile disasters such as Rise of the Robots and Daikatana provided a meaningful exception to this rule. The reason I say this is because I firmly believe that had the internet been as widely used in 1993 as it is today, this game would’ve been verbally destroyed in countless comedic review shows with the more cynical members of the community using it as evidence for the medium’s supposed devolution.

Isle of the Dead is the Ride to Hell: Retribution of its day, as it manages to do absolutely everything wrong. Not only is it a repetitive, outdated first-person shooter, it’s also one of the worst adventure games ever conceived with a forgettable plot and a level of interactivity utterly dwarfed by that of Colossal Cave Adventure, the first known work of interactive fiction. Under no circumstances should you try this game out; even as an ironic excursion, there would be a distinct lack of good times to be had. Most horrible works have to be complacent with offending a single genre; the developers at Rainmaker Software somehow made a game that’s an insult to two simultaneously.

Here it is, ladies and gentlemen: the single most accurate description in the game.

Final Score: 1/10

Advertisements Share this: