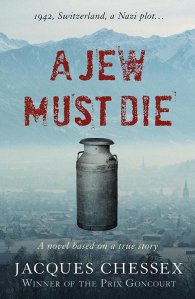

Chessex, Jacques (2009), Un Juif Pour L’exemple, Grasset

ISBN 09782253129615-4

[English edition: Chessex, Jacques, A Jew Must Die, Bitter Lemon Press

ISBN 9781904738510

translated by W. Donald Wilson]

I’ve long meant to write something about the Swiss novelist and poet Jacques Chessex, whose work I admire greatly. Today’s election pushed me to reread the last novel he published during his lifetime (it’s not his final novel, two additional novels were published posthumously), the searing and quite excellent A Jew Must Die. The sensational English title hides the matter-of-fact nature of the book. In French, its title is Un Juif Pour L’Exemple (~ “a Jew to make an example of”) and while some of the leading characters in the book are indeed subsumed by hate, the murder at the center of the book is based on political calculations, in addition to antisemitic hatred. The story had been told in a book and documentary in the 1970s (“Le crime nazi de Payerne – Un juif tué pour l’exemple”), hence the title of the original novel. The murder and its description is horrifying, but this is not about the murder per se. Chessex wrote a novel about the village he was born in and the social context in which a murder like this could have arisen. The novel shows us the complacent, maybe complicit village population, and a police force that doesn’t particularly care about the fate of this missing Jew. The reaction to the novel’s publication, finally, that treated Chessex with anger and derision, confirms the quiet anger that spurred Chessex to write a book about an event that both anticipates the Shoah and exemplifies much that led to it. Chessex’s writing in the novel is excellent, using a nominally neutral, sober style, but infusing it with passion, with occasional cascades of rhetoric and description. The description of the murder, with its three entrances, like a dark mirror of a fairy tale quest, is terrifying and compelling. Everything about this novel, except for its size, is enormous; towering above it all is the conscience and care of Chessex and his literary and historical conscience. I don’t think it is his best novel necessarily (from the ones I read, I think both L’Ogre and Hosanna are slightly better?), but it is a very good novel and certainly better than most fiction that is published about the Shoah these days. Chessex was a great writer and this novel shows why: a sharp intelligence, sense of style and conscience combined to create this dense but essential book. I have not read the translation, and while the change in titles makes me worry a bit, the novel doesn’t pose obvious linguistic puzzles, so I can’t see why the translation shouldn’t be fine. Read this book in whatever form you can find it. It is very good.

I’ve long meant to write something about the Swiss novelist and poet Jacques Chessex, whose work I admire greatly. Today’s election pushed me to reread the last novel he published during his lifetime (it’s not his final novel, two additional novels were published posthumously), the searing and quite excellent A Jew Must Die. The sensational English title hides the matter-of-fact nature of the book. In French, its title is Un Juif Pour L’Exemple (~ “a Jew to make an example of”) and while some of the leading characters in the book are indeed subsumed by hate, the murder at the center of the book is based on political calculations, in addition to antisemitic hatred. The story had been told in a book and documentary in the 1970s (“Le crime nazi de Payerne – Un juif tué pour l’exemple”), hence the title of the original novel. The murder and its description is horrifying, but this is not about the murder per se. Chessex wrote a novel about the village he was born in and the social context in which a murder like this could have arisen. The novel shows us the complacent, maybe complicit village population, and a police force that doesn’t particularly care about the fate of this missing Jew. The reaction to the novel’s publication, finally, that treated Chessex with anger and derision, confirms the quiet anger that spurred Chessex to write a book about an event that both anticipates the Shoah and exemplifies much that led to it. Chessex’s writing in the novel is excellent, using a nominally neutral, sober style, but infusing it with passion, with occasional cascades of rhetoric and description. The description of the murder, with its three entrances, like a dark mirror of a fairy tale quest, is terrifying and compelling. Everything about this novel, except for its size, is enormous; towering above it all is the conscience and care of Chessex and his literary and historical conscience. I don’t think it is his best novel necessarily (from the ones I read, I think both L’Ogre and Hosanna are slightly better?), but it is a very good novel and certainly better than most fiction that is published about the Shoah these days. Chessex was a great writer and this novel shows why: a sharp intelligence, sense of style and conscience combined to create this dense but essential book. I have not read the translation, and while the change in titles makes me worry a bit, the novel doesn’t pose obvious linguistic puzzles, so I can’t see why the translation shouldn’t be fine. Read this book in whatever form you can find it. It is very good.

A Jew Must Die is based on a true story which the inhabitants of the village in question would love to forget. It’s ancient history! tells him one of the antisemites he portrays in the book upon meeting him 25 years after the events (though this particular person regrets nothing). An ardent Nazi, an antisemitic priest, and some farmers get together and decide to murder a Jew as a sign to all the other Jews who are sucking the lifeblood from the country, as they see it. Chessex is clear to distinguish between the general opinion and resentment towards Jews, which is generally shared in the area at the time, and the gruesome murder of the specific Jew in the novel, which is undertaken in secret by a small group of people. They decide to make an example of one of the Jews and pick a local merchant. After murdering him (in a spectacularly written scene, as I said), they cut him up and stuff him into milk cans like the one on the cover of the English edition. I’m not really spoiling you here – Chessex doesn’t rely on that kind of suspense. He introduces the Jew who will be murdered pretty late – he’s more interested in the social and psychological description of the murderers. Villages being villages, eventually they are found out, and convicted to jail sentences of varying lengths. The antisemitic priest fled the country and moved to Germany where he was arrested after the war and extradited to Switzerland. Yet there is no sense of relief in that. No jail can erase the tragedy from history – and moreover, the fellow villagers, murmuring assent to calumnies hurled at Jews in bars and casual conversations, have not been jailed or even prosecuted, not having committed a crime in the conventional sense.

While the events have happened as described, and all the people in the novel go by their real names, Chessex never makes the documentary character of the novel into a character in the book that competes with the horrifying events described within, in stark contrast to the vain self-reflections in books like Laurent Binet’s HHhH, which I like less with every year that passes. My too favorable review is here. There are a few asides, some conversations with the reader about plausibility but they don’t serve to undercut the story, they just underline the authorial urgency that powers the whole novel. Chessex never discusses or cites his sources, but since he was a boy when the murder happened, and the principal actors all went on trial, he has access to both firsthand knowledge and an obvious source of documentation. Yet by not discussing this, we are not asked to admire his skill or ability to research or present the information, we are free to deal with the nature of what happened. He devotes one single chapter to reflections about himself and his motivations in writing the book, but he closes with remarks on the murder victim’s funeral. The self-reflections are primarily meant to assuage the writer’s guilt – not in inventing details, but in writing fiction about the Shoah at all. “Je raconte une histoire immonde et j’ai honte d’en ecrire le moindre mot,” he writes, and it is a testament to his writing that we fully believe that he feels conflicted and shameful about writing this book. In Binet’s book, an assertion like that would have smelled of a performance of shame, and yet in Chessex writing, it becomes part of the urgent fabric of the book. Writing about the events makes the author complicit, in a sense, but coming from the same village, going to school with the children of the murderers already puts the author in a difficult situation. The novel ends on a prayer for forgiveness and we understand. There are people who are able to shrug off the way they are complicit in the horrors of this world, and it never fails to stun me. Chessex goes down a different path: understanding what happened and why it happened is step one to ensure it doesn’t happen again.

While the events have happened as described, and all the people in the novel go by their real names, Chessex never makes the documentary character of the novel into a character in the book that competes with the horrifying events described within, in stark contrast to the vain self-reflections in books like Laurent Binet’s HHhH, which I like less with every year that passes. My too favorable review is here. There are a few asides, some conversations with the reader about plausibility but they don’t serve to undercut the story, they just underline the authorial urgency that powers the whole novel. Chessex never discusses or cites his sources, but since he was a boy when the murder happened, and the principal actors all went on trial, he has access to both firsthand knowledge and an obvious source of documentation. Yet by not discussing this, we are not asked to admire his skill or ability to research or present the information, we are free to deal with the nature of what happened. He devotes one single chapter to reflections about himself and his motivations in writing the book, but he closes with remarks on the murder victim’s funeral. The self-reflections are primarily meant to assuage the writer’s guilt – not in inventing details, but in writing fiction about the Shoah at all. “Je raconte une histoire immonde et j’ai honte d’en ecrire le moindre mot,” he writes, and it is a testament to his writing that we fully believe that he feels conflicted and shameful about writing this book. In Binet’s book, an assertion like that would have smelled of a performance of shame, and yet in Chessex writing, it becomes part of the urgent fabric of the book. Writing about the events makes the author complicit, in a sense, but coming from the same village, going to school with the children of the murderers already puts the author in a difficult situation. The novel ends on a prayer for forgiveness and we understand. There are people who are able to shrug off the way they are complicit in the horrors of this world, and it never fails to stun me. Chessex goes down a different path: understanding what happened and why it happened is step one to ensure it doesn’t happen again.

I may have reread the book today because of the possibility of Marine LePen becoming President of France, in connection with the French language of the book and the rural support of the FN in France. It seemed fitting. However. Chessex is a Swiss writer and the two books that most came to mind upon rereading this one are also Swiss. They are two plays by Max Frisch and Friedrich Dürrenmatt, two of Switzerland’s best writers in all of that country’s literary history. Both spent a good deal of their writing life criticizing Switzerland, and criticizing the Swiss role during the Third Reich. Frisch’s play Andorra, read by practically all German high school students at some point, focuses on the mob mentality of hate, as does Dürrenmatt’s play The Visit. Frisch doesn’t name anyone, in fact, his play is a thought exercise, not even naming Jews as the persecuted group, and Dürrenmatt’s play is even further removed from the historical background. Both, however, manage to describe with remarkable skill how volatile villages and small towns can be if given the right ideology and the right solution to perceived problems. However, their playful distance to historical events, the authorial insistence on cleverness and skill over historical urgency has always felt a bit off to me. If you look at Frisch’s reaction to and treatment of Celan, you should feel an even stronger sense of unease. Jacques Chessex wrote a novel that insists on the historical and local roots of the events that happened; you can’t abstract from the facts without losing some vital elements. Both Frisch and Dürrenmatt’s plays are important, but the extraordinary quality of Chessex novel becomes more pronounced when you compare it to the work of fellow French writers.

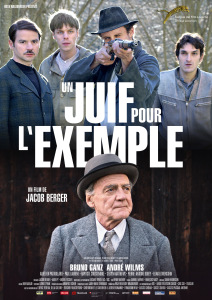

Chessex’s novel caused outrage in his home village. Insults rained, ranging from articles, speeches to a carnival float showing the writer pulling a bunch of milk cans out of which bones poked, in essence confirming much the author didn’t make entirely explicit. Payenne, even many decades after the murder, is still Payenne. There is a straight line leading from the events of the novel to us today, the contingency of history, and this book, quiet and angry, gruesome and sad, offers us a link. As a German, this link between 1940s hate and today’s population rings true, as does the wish to forget about history. My East German grandmother’s village used to have a small, but infamous concentration camp but nobody in the village ever mentions it or likes it being mentioned. It’s a village full of people complicit in unbelievable crimes against humanity where nobody ever talks about it, except to discuss tales of being sometimes hungry during war time. Today, the village’s youth is full of current or former neo-nazis and nobody sees the connection. German culture and literature performs shame, dishonest, with a slight self-righteous twist. It is what makes so much of German literature not written by immigrants so dull, as I’ve noted here and there. Care and honesty in this literature is rare these days. So as someone feeling the need for an écriture like that, Jacques Chessex’ achievement shines even brighter. Jacques Chessex was a fantastic writer and Un Juif Pour L’Exemple is an important, a great novel – and I’m not sure the title and layout picked by Bitter Lemon Press are entirely appropriate, but my misgivings are entirely overshadowed by the gratitude I feel for the fact that they translated this book to begin with. There’s also a movie out, directed by Jacob Berger. I have not been able to get my hands on a copy, virtual or physical, yet, but as far as I can tell, Berger includes the reaction to the novel as part of the movie’s story, which is an interesting and laudable decision. I cannot vouch for the movie but I can vouch for the novel. Read it. That is all. PS. If you have an idea how I can get my fingers on that dang movie, please tell me.

Chessex’s novel caused outrage in his home village. Insults rained, ranging from articles, speeches to a carnival float showing the writer pulling a bunch of milk cans out of which bones poked, in essence confirming much the author didn’t make entirely explicit. Payenne, even many decades after the murder, is still Payenne. There is a straight line leading from the events of the novel to us today, the contingency of history, and this book, quiet and angry, gruesome and sad, offers us a link. As a German, this link between 1940s hate and today’s population rings true, as does the wish to forget about history. My East German grandmother’s village used to have a small, but infamous concentration camp but nobody in the village ever mentions it or likes it being mentioned. It’s a village full of people complicit in unbelievable crimes against humanity where nobody ever talks about it, except to discuss tales of being sometimes hungry during war time. Today, the village’s youth is full of current or former neo-nazis and nobody sees the connection. German culture and literature performs shame, dishonest, with a slight self-righteous twist. It is what makes so much of German literature not written by immigrants so dull, as I’ve noted here and there. Care and honesty in this literature is rare these days. So as someone feeling the need for an écriture like that, Jacques Chessex’ achievement shines even brighter. Jacques Chessex was a fantastic writer and Un Juif Pour L’Exemple is an important, a great novel – and I’m not sure the title and layout picked by Bitter Lemon Press are entirely appropriate, but my misgivings are entirely overshadowed by the gratitude I feel for the fact that they translated this book to begin with. There’s also a movie out, directed by Jacob Berger. I have not been able to get my hands on a copy, virtual or physical, yet, but as far as I can tell, Berger includes the reaction to the novel as part of the movie’s story, which is an interesting and laudable decision. I cannot vouch for the movie but I can vouch for the novel. Read it. That is all. PS. If you have an idea how I can get my fingers on that dang movie, please tell me.

*

As always, if you feel like supporting this blog, there is a “Donate” button on the right.