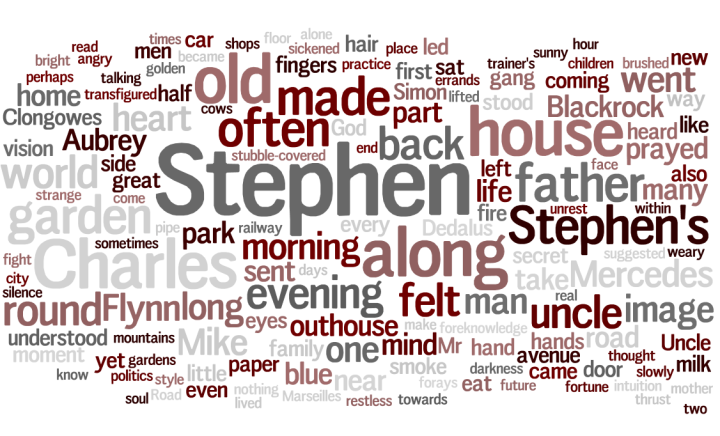

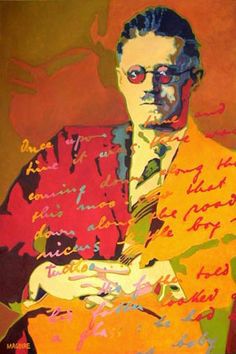

Irish writers are often noted both for their irony and for their humour, and Joyce uses a great deal of comic irony in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young man. Irony is not always comic. It is ironic when a hero kills his own son not knowing who he is, but this irony is wholly tragic. It is ironic that a Christmas party meant to be the occasion of peace and goodwill should turn into a violent family row and a virulent exchange of abuse. It is sad too, and Stephen feels its sadness, but it also has its comic side. We smile when Dante, a rather self-important person conscious of her own dignity, is turned into a screaming virago quivering with rage, and when Mr Dedalus lets off steam in comic abuse of Church dignitaries.

Humorous irony in literature often revolves around the way self-important people are brought down to earth with a bang. In A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Stephen is the main concern of the author and he happens to be a rather self-important and pretentious person. Joyce often punctures his pretentiousness – not in his own eyes and not in the eyes of other characters, but in the reader’s eyes. For instance, when Stephen makes his righteous protest against being unjustly punished by Father Dolan, he pictures himself like some great public figure of history standing up against tyranny. The little boy appealing to his headmaster sees himself in this grand light and when his protest has been accepted, he resolves not to take advantage personally of his vanquished foe, and we smile at his childish self-importance.

Stephen’s romantic dreams often evoke this indulgent smile in the reader. He pictures himself, at the end of a long series of heroic adventures, proudly declining Mercede’s offer of grapes. When he helps to lead a gang of boys, he sets himself apart from the others by not adopting their symbols and uniform, because he has read that Napoleon also remained unadorned. These comic comparisons made by the little boy are rich in ironic humour.

These are of course the kind of imaginative exaggerations which are common to childhood. But they lead to less usual extravagances in the growing artist. When a boy sits down, as Stephen does, to write a poem to a girl, and begins it by imitating Lord Byron’s habit of entitling such poems, but finishes up staring at himself admiringly in the mirror, the gap between supposed intention and reality is wide. Later Stephen imagines a stage triumph before Emma’s eyes and rushes off to claim his due of feminine admiration only to finish up in a squalid corner of the city amid the smell of horse urine. These contrasts are the stuff of irony. So is the contrast between the boy’s glamorous dreams of himself as a romantic lover and the actual experience to which they lead in a city brothel.

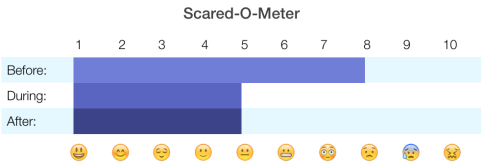

The retreat sermons are a sustained ironic piece, and the irony this time is not primarily at the expense of the hero but of the Catholic Church and its clergy. The sermons seem to start reasonably enough but gradually become a burlesque (the Tommy Tiernan treatment!) of the kind of teaching given in retreats. That is to say, they follow the course of traditional moral exhortation but push the examples to such an extreme that the effect is laughable. A further irony is that the ingenuity with which torments are seemingly devised by God and the relish with which they are described by the priest are not congruous with notions of a loving God and a religion of love. Equally ironic is the meticulous and literal way in which Stephen tries to mortify his senses and discipline his mind. The sermons plainly have had the effect on him which the priests had hoped for. Now that Stephen is repentant we naturally warm to him in sympathy, but we still smile at the degree of vanity and self-centeredness he shows in trying to model himself anew.

In some respects, the irony at Stephen’s expense is sharpest in the last chapter of the book. For when he becomes a student his aspirations are aimed higher and higher. The contrast between these aspirations and the reality around him is often laughably sharp. At the end of Chapter 4, for instance, Stephen has enjoyed raptures expressed in language of lyrical beauty. At the beginning of Chapter 5, he is drinking watery tea and chewing crusts of fried bread at a dirty kitchen table. Joyce puts these two episodes together with comic intent. Again Stephen propounds his high doctrine of beauty to his fellow students who, for the most part, have only crude and vulgar witticisms to contribute to the conversation.

Stephen dismisses real living beauty from his mind in order to theorise about beauty with his intellect. Inspired suddenly by Emma’s beauty, he writes a poem in a language utterly removed from the idiom of living human relationships. It is poetry so precious and “high-falutin” that real feeling is left out. The irony of praising Emma so richly in secret and virtually snubbing her when she makes natural friendly approaches is both amusing and rather sad. Not for the first time, we want to shake Stephen to try to knock some sense into him; above all to make him a little more human.