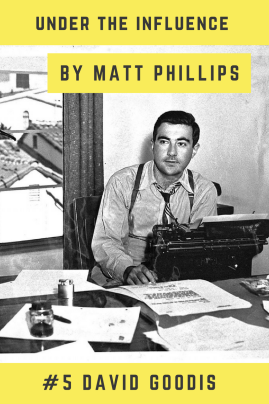

It’s fitting that I found David Goodis’s novel, Shoot the Piano Player, in a dusty used bookstore in San Diego, California. The place––on the corner of 35th and Adams––was overrun with angry house cats and smelled like a tomb. For some odd reason, the book itself––originally titled Down There––had flecks of dirt between its pages. Maybe somebody unearthed it from a shallow grave and tried to sell it for gambling money.

A story like that wouldn’t surprise me when it comes to David Goodis.

He kept shit dark; that’s how he liked it.

The opening sentence in Shoot the Piano Player? “There were no street lamps, no lights at all.”

For Goodis to start a story in such darkness makes it necessary to bring his characters to the light. To any light, perhaps. When it comes to the novel’s protagonist, Eddie the piano player, that means coming to terms with who and what he is. Eddie might have been a concert pianist, might have been famous, might have been a goddamn winner in a sea of losers.

But the final truth is that Eddie is down and out.

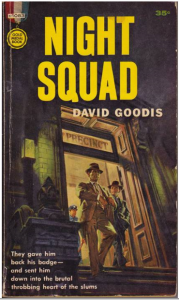

David Goodis somehow knew in his soul what it was to be down and out; more than anything else, that’s what you get from his novels, a surging and ceaseless sense of dread. You see it in Night Squad, in Cassidy’s Girl, in Nightfall.

Noir tells us that, for most people, things do not turn out as we hope.

In other words: Do not believe the advertising agencies.

Goodis knew this truth better than anyone, and he lived it out when he died a mysterious death in Philadelphia, the city of his birth. Two decades earlier, he had it made as a scriptwriter in Hollywood, but Goodis gave all that up––no story book ending here. Noir, people.

I do not know if Goodis had love or money when he died, but I doubt he had much of either.

And he was not aware that, after his death, his novels would be re-examined by a cadre of critics, readers, and burgeoning crime writers. And those very same novels would be seen not as run-of-the-mill pulp fiction, but rather as high drama done in the most accessible of forms. When you read Goodis, you find elements of tragedy and humor common across all the great art forms. You see the fall from grace in Night Squad when ex-policeman Corey Bradford argues with his own badge: “Without sound he’d say to the badge, what the hell, jim—we ain’t tryin’ to kid nobody; we sure ain’t out to cause grief or suck blood. It’s just that we wanna live and have fun and be happy; and we wish all others the same.” And you see the depths of addiction mined to the core in Cassidy’s Girl when Cassidy laments, “…in the deep ridges of his mind he saw the bottle as a loathsome, grotesque creature that had lured Doris and captured her and pleasured itself with her, draining the sweet life from her body as it poured its rottenness into her. He saw the bottle as something poisonous and altogether hateful, and Doris completely helpless in its grasp.”

If Goodis didn’t have love when he died, he sure as shit has it now.

As a writer of noir myself, Goodis taught me that it isn’t a choice to write about flawed people––it’s a calling and, for some damn reason, there are a few chosen ones who know how to do it…Who must do it. That’s why my own work deals with the bitter fact that, for lots of us, we are what we are, and there’s no escaping our faults and the faults of our world. Like my characters in Accidental Outlaws—to a man (and woman) they’re all warped by the desert region where they live. Their bones are seasoned with dirt. In my book Three Kinds of Fool, Jess Forsyth is a rehabilitated convict. But when he runs into an old friend, Jess’s previous life begins to cast a long shadow on him. In Bad Luck City, my novella set in the Vegas underbelly, a washed-up reporter named Sim Palmer encounters the sins of his father. Palmer’s dark journey illuminates the paradox of loving one’s family, no matter the bad deeds they’ve done. These characters—and their desperate lives—are the notes I must play.

And, like Eddie in Shoot the Piano Player, if you know how to play, you better damn well play. Doesn’t matter if it’s in a neighborhood bar or a fancy concert hall.

You can play, you better damn well play.

David Goodis may not be studied in the guarded halls of the ivory tower, but the man knew how to play. And when he sat down at his desk, rested his fingers on the typewriter, and punched those keys…

Jeez, a sound came out––and it was music.

Bio: Matt Phillips lives in San Diego. His books include Accidental Outlaws, Three Kinds of Fool, Redbone, and Bad Luck City. He has published short fiction in Shotgun Honey, Tough Crime, Near to the Knuckle, Out of the Gutter’s Flash Fiction Offensive, Manslaughter Review, Powder Burn Flash, and Fried Chicken and Coffee.

Website: www.mattphillipswriter.com

Advertisements Share this: