For a period of time in September 1969, barricades in many Belfast districts were effectively guarded jointly by the British Army and IRA, under the guise of the local Citizen’s Defence Committees (CDC). The Central CDC in Belfast was chaired by Jim Sullivan who was also acting O/C of the IRA’s Belfast Battalion. The Belfast O/C, Billy McMillen, had been arrested prior to the August 15th attacks and interned without charge even though it had initially reported that he was being held for illegal possession of a firearm.

A CDC had been formed in Derry early in August 1969 and elsewhere later in the same month. The name mirrored the ‘Ulster Constitutional Defence Committee’, formed in 1966, and its precursors, like the ‘Omagh Citizen’s Defence Committee’ and another set up in Fermanagh in 1953-4 to co-ordinate the local unionist campaigns to prevent Catholics obtaining jobs and housing. Creation of CDCs in 1969 provided an umbrella organisation in which the likes of ex-servicemen, Catholic clergy, political representatives, former IRA volunteers and others could co-operate with each other and the IRA without having to be publicly presented as a face of the IRA, even though it was effectively led and directed by the IRA.

The use of shifting organisational identities had been pushed by Cathal Goulding and others for some time. IRA statements using names like ‘Resistance Forces’ and ‘Citizens Army’ had been appearing even before the formal end of the border campaign in 1962. This was to accelerate into the early 1970s (and later) as the Goulding-led Official IRA was to continually shift it’s identity.

When the British Army was deployed in mid-August 1969, it also brought into play a well established counter-insurgency strategy as well as its best known advocate and practitioner in Brigadier Frank Kitson. This included establishing its own intelligence gathering capabilities in the absence of any effective intelligence held or shared by the RUC, Special Branch or the unionist government.

At a high level this meant that the ongoing attempts to negotiate a removal of barricades from districts that had been attacked in mid-August could provide a pretext to profile the CDC (and effectively IRA) leadership from close-in. On 6th September, Jim Sullivan, chair of the CDC and acting Belfast Battalion O/C, met with the Major General Tony Dyball, the British Army’s deputy director of operations in the north (revealed in that weekends Sunday papers). This happened alongside meetings with Catholic clergy and others over defence of the districts that had come under attack. Sullivan and Dyball agreed that the barricades would now be guarded by British soldiers alongside the CDC.

That weekend, three barricades in Albert Street were taken down and replaced with British Army barriers and soldiers maintained a presence at them, as had been agreed. The press was rife with rumours that the discussion where this was agreed wasn’t between the British Army and local clergy as publicly claimed, but between the British Army and IRA. But the agreement reached in Albert Street wasn’t replicated elsewhere as almost nightly attacks on isolated Catholic families continued.

That Sullivan pushed for the removal of barricades and delegating the defence of Albert Street to the British Army cut directly across the later narrative promoted by the Officials that the violence didn’t come from the communities and the general unionist population but, rather, was directed by forces from elsewhere (typified by the likes of the British Army). Sullivan personally pushed for the removal of the Albert Street barricades, certainly this is, at least, how it is represented in the contemporary press. Around 300 barricades had been erected across the city but the example of Albert Street didn’t lead to further exchanges of hastily erected barricades for British Army barriers. Within a couple of days, Sullivan was threatening to re-erect barricades if the British Army removed them without agreement. Sullivan, along with Stormont MPs Paddy Devlin and Paddy Kennedy then travelled to London to try and meet senior British government figures for discussions.

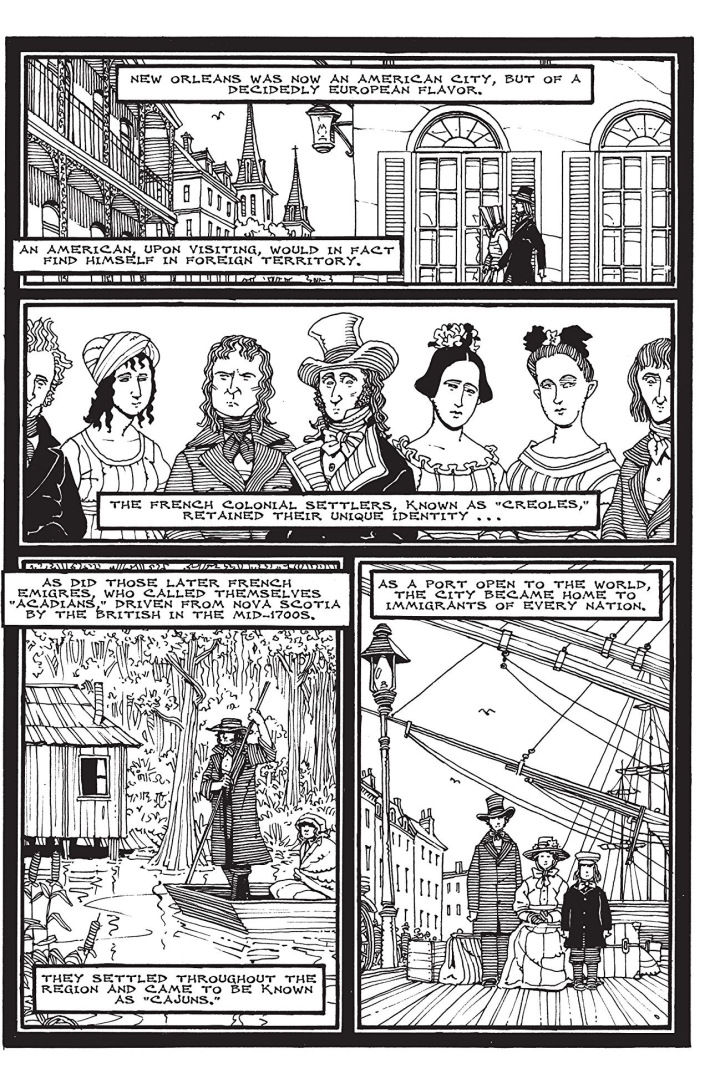

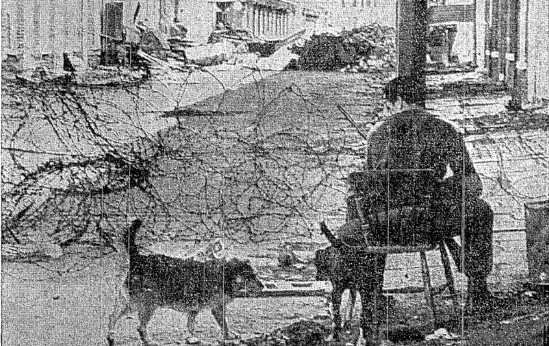

British Army preparing to erect the so-called ‘peace line’ in Cupar Street (Irish Press, 11th Sept 1969)

British Army preparing to erect the so-called ‘peace line’ in Cupar Street (Irish Press, 11th Sept 1969)

Meanwhile, a demarcation line was being erected by the British Army along the boundary of the most threatened areas (described as a ‘peace line’). This was continuing over the course of the next week and was mostly completed by 16th September. Pressure was growing to have the other barricades removed and the CDC organised meetings of delegates from the various districts to gauge the mood. Assurances were given by the British GOC that the army would provide adequate security and that the Special Powers Act would not be applied. Again, Jim Sullivan then pushed for the barricades to come down but often agreements had to be made on street by street basis indicating a high level of discomfort over the proposed arrangement. This was not misplaced.

Given how the British Army was aware of the limitations of the quality of the intelligence gathered by the RUC and the unionists. An agreement to jointly guard barricades with the CDC now provided the British with a pretext to create its own profile of the IRA. Kitson himself had requested a meeting with the IRA leadership (which was turned down), but John Kelly has recounted that the depth of contact between the IRA and British Army extended as far as a British officer providing a class on machine guns. Kelly suspected that this was to evaluate the level of the technical capacity of the IRA (and presumably to identify the relevant personnel). On top of the failure to have adequately prepared to defend districts from attack in mid-August, the rapprochement between his Belfast IRA leadership and the British Army was also to be held against Cathal Goulding by many in Belfast.

Peace lines in Dover Street (Irish Press. 13th Sept 1969)

Peace lines in Dover Street (Irish Press. 13th Sept 1969)

One barricade that was slow to come down, was the one that had been erected at the top of the New Lodge Road, at it’s junction with the Antrim Road. This too was taken down on Tuesday 17th September. As with elsewhere, it was then replaced with a British Army barricade which was one of those jointly guarded by the 2nd Light Infantry and the CDC.

On the Saturday night, Tony McNamee, Brendy Magee, Mark O’Connor and Hugh Adams were playing cards on a windowsill outside the Duncairn Arms at the top of the New Lodge Road. As some men were seen approaching the traffic island from Hallidays Road (leading back to Duncairn Gardens), a soldier, Lance Corporal Peter Reid went to warn the four young men to withdraw behind the barrier for safety. Shots were then fired from the other side of the traffic island, at a range of about twenty metres. All five were wounded. Reid, McNamee and Magee were the most seriously injured, with Reid sustaining facial injuries. Following the shooting a local taxi firm was also attacked.

As crowds gathered at either side of the barricade, hundreds of soldiers were rushed into the area. Hallidays Road was searched and a weapon recovered in a house in Stratheden Street. Four men from the unionist Tigers Bay district, Andrew Salters, Arthur Ingram, John Strain and William Jamieson, were arrested (in the end only Jamieson was found guilty, receiving a two year sentence). The next day they were charged with possession of the shotgun used in the shooting. At their remand hearing, on the Monday morning, RUC Head Constable Thomas McCluney explained to the court that the accused fired the shots as ‘feelings had been running high’.

On the Sunday, the CDC for the New Lodge and Docks had met and agreed further security measures. This included introducing a graduated curfew for children (8 pm) and others not involved in patrols and defence (10 pm). The CDC put in place a rota and schedule of patrols for the defence of the area. Oliver Kelly (vice-chairman of the CDC) said the shooting had been a salutary lesson for all those involved. The Major in charge of the 2nd Light Infantry in the district admitted that the hadn’t believed that they would be fired upon by unionists.

But on that Sunday night, unionists left a 2lb gelignite bomb in Exchange Street in the Half Bap area (immediately to the south of the New Lodge and North Queen Street). It exploded in the middle of the street, shattering windows in thirty houses although no-one was badly injured. Immediately a barricade was re-erected at the end of Exchange Street. The same pattern was to follow over the next week as local violence prompted the return of barricades.

The same weekend, the Belfast IRA O/C, Billy McMillen, was released from internment. On the Monday, against the backdrop of the New Lodge Road shooting and the bombing of Exchange Street, McMillen called a meeting of the Belfast IRA staff in Cyprus Street. Famously, he was confronted about the rapidly changed political landscape in a meeting regarded as critical to the fragmentation of the republican movement that accelerated over the next few months.

Advertisements Share this: