Every year, 7,000 children go missing in Delhi and 1,500 of them remain untraced. Many of them are lured by traffickers to be pushed into forced labour and prostitution. Inadequate punishment keeps the illegal trade thriving. DNA finds out that of the 544 persons charge-sheeted last year for kidnapping, only 50 were convicted

Ashima was too young to remember when her parents died. She stayed at her maternal aunt’s house in Bihar’s backwaters. She was kidnapped by unknown people and brought to Delhi when she was nine. She was kept in a house that always looked strange to her. She was given good dresses and food. But the innocent girl had no idea of the future that lay ahead.

On her 11th birthday, she was taken to a brothel on Delhi’s GB Road — the city’s main red light district stretching from Ajmeri Gate to Lahori Gate parallel to the railway tracks. One day when she said ‘no’ to a much older customer, she was tied to a pole and brutally thrashed with belts, boots and sticks. She was then raped by five men. For four years, she was forced to sleep with a number of customers every night, as multi-storey brothels came alive and shops shut downstairs.

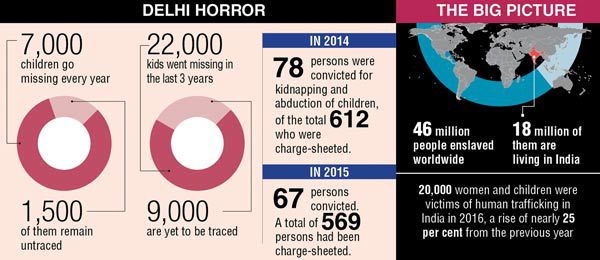

There are an estimated 46 million people enslaved worldwide, with more than 18 million living in India, according to the 2016 Global Slavery Index. Thousands of people – largely poor, rural women and children – are lured to India’s towns and cities each year by traffickers who promise good jobs. Some end up as domestic workers, or are forced to work in small industries. Many are pushed into brothels where they are sexually exploited.

Almost 20,000 women and children were victims of human trafficking in India in 2016, a rise of nearly 25 per cent from the previous year, government data released in March this year showed. The highest number of victims were recorded in West Bengal. Police officials also attribute the rise to increased public awareness of trafficking-related crimes, and more police training.

Every year, more than 7,000 children go missing, and 1,500 of them remain untraced in Delhi, the second highest in the country after Maharashtra. Many of them are never found. Data tabled in the Lok Sabha recently revealed that in the past three years more than 22,000 children went missing in Delhi. Nine thousand are yet to be traced.

As many as 6,921 children were reported missing in 2016, of which 5,109 were traced while the remaining 1,812 could not be found, latest government data shows. In 2017, till July, 3,544 children were reported missing, of which 1,372 are yet to be traced, the data shows.

But only 78 persons were convicted for kidnapping and abduction of children in 2014, of the total 612 who were charge-sheeted. In 2015, the number of persons convicted remained 67. A total of 569 persons had been charge-sheeted.

In May this year, following a tip-off, a team of the Delhi police and the Delhi Commission for Women (DCW) raided brothel number 58 on GB Road and rescued Ashima. Shocked, and reluctant to speak, she initially said that she was 20. But as she opened up and narrated her ordeal, she admitted that she was 15. The brothel owner had instructed her that whenever there was a police raid she should reveal her age as 20, and that she was in this profession by choice.

She also told the police that in the past she had tried to escape from the brothel a couple of times, but was always caught as there are CCTV cameras installed all around. Every time, she was brutally beaten and thrown again into prostitution.

The US continues to place India in tier-2 of its annual report on human trafficking, arguing that the country does not fully meet the minimum standards for elimination of trafficking. “Most of India’s trafficking problem is internal, and those from the most disadvantaged social strata — lowest caste Dalits, members of tribal communities, religious minorities, and women and girls from excluded groups — are most vulnerable,” a recent US State Department report said.

However, it’s not just girls. Ayub can barely recall how he landed with a family in Lucknow. “I was very young. I do not remember how I reached there. I later realised that it was not my family. I was nothing more than a servant. Abuses and tortures were a routine,” he said.

It was in 2012 that he somehow reached the New Delhi railway station, and stayed there for a year. During this time, he sold newspapers, water bottles at the station, begged, and was also often made to travel to Rajasthan to beg. It did not take him long to understand that he was again in the hands of a syndicate that exploited beggars.

“It was in 2012 that I came to Delhi and met with an accident. None of those who claimed to be my caretakers came forward to help with the treatment. I was hospitalised for some time, and then was handed over to Asha Grih, a rehabilitation programme run by Believers Church Organisation of Bishop K.P. Yohannan. I was probably in safe hands for the first time”.

A year later, Ayub was admitted to a school. He is in Class 9 now. “I want to be an engineer,” he said with a smile.

Ref: http://www.dnaindia.com/india/report-childhood-in-chains-2534784

Advertisements Share this: