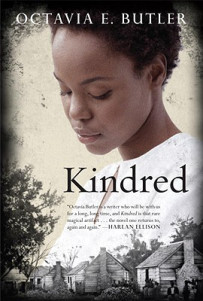

Author: Octavia E. Butler

Type: Fiction, novel

Published: 1979

I read it: November 2017

There is a brilliant conceit at the center of Octavia E. Butler’s classic novel Kindred, and it’s not necessarily the time travel. Even though you can find the book on the sci-fi shelves, Butler prefers to call it a “grim fantasy” instead, pointing out that there’s “absolutely no science in it.” The time travel is crisp and sharp, sending the protagonist into instant confusion, because it offers no explanation of itself. The only rule is that it sends her to slave-owning days a couple centuries in the past via a physio-emotional connection to an ancestor of hers.

And that’s the real genius of the book’s plot: the modern black woman, Dana, is so entwined with the destiny of the white Rufus, son of a plantation owner, that she has to keep him alive to keep herself alive. She quickly realizes the intensity of her dilemma:

I was the worst possible guardian for him—a black to watch over him in a society that considered blacks subhuman, a woman to watch over him in a society that considered women perennial children. I would have all I could do to look after myself. But I would help him as best I could.

Dana gets hurtled back in time whenever Rufus’ life is in danger, and there’s another layer to why she must save him from himself each time: she figures it’s the only way to keep her family line from being broken. Butler doesn’t explore the potential paradoxes should this happen, but Dana feels on an elemental level that she can’t stand by and watch Rufus die. Besides, the first time she meets him he is only a boy, and then she hardly ages in her own timeline before seeing him again at various ages of his youth and young adulthood. Their relationship grows ever more complex, and it’s this humanistic interplay that makes the novel worth reading. The white slave-owners aren’t cast only as monsters without redemption, although there are plenty of terrible scenes throughout the book. Yet another layer is making Dana’s husband, Kevin, white himself, and having him also get sucked back in time and stuck for a number of years. He struggles to not let that past wear him down and shape him into something less than he is. Dana worries that “the place, the time would either kill him outright or mark him somehow.”

Dana has it worse than Kevin, obviously, and her dawning disappointment about how and why a slave can come to accept her position in life is the slow tragedy of the book. She tries to stay independent and just, knowing she has a moral and educational perspective that others in the past timeline lack. But she witnesses that “slavery was a long slow process of dulling,” and the ethical compromises she has to make as the story progresses are severe. There’s no way for her to escape the physical and emotional realities of slavery, and the reader is forced to awkwardly confront scenarios that gnaw away at the righteous indignation we feel and undermine our internal hopes that we could somehow rise above the situation were we forced into something similar. The past says otherwise.

Advertisements Share this: