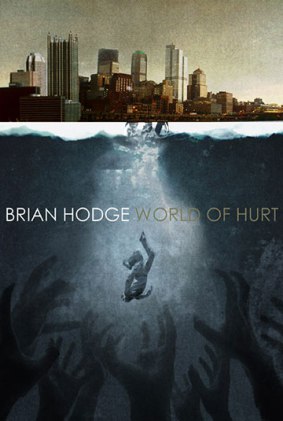

Like many readers of horror lit I discovered the work of Brian Hodge through the legendary Dell/Abyss line, which landed on shelves in the early 1990s like a demon with a napalm kiss and a razor-wire hug. I was addicted to those books, and snatched up each new release. It was through that line of books that I discovered several writers whose work would not only change everything I thought about horror, but changed the way I thought about my own writing. Through their stories, they tore open my psyche, battered my heart, and spread like a cackling virus through my imagination, fomenting ideas and characters I had never dared believe I could write about. Because a lot of those characters were way too much like me, and that scared the shit out of me. I didn’t realize I could be that vulnerable and still live to tell about it. And I loved it!

At the top of that list is Brian Hodge. I gush a bit about his work and his influence on me later in this interview, so I won’t get into that here. I will say this, though: Brian was the first writer I ever worked up the guts to write to. See, around the time I was immersed in his work, I was just starting to learn about the internet. With the advent of email in my life, and by seeking out artists I admired online, I discovered it was pretty easy to contact them. Mostly I emailed musicians, because, not being a musician myself, I wasn’t intimidated by them. Writers, though? Well, anyway, I found Brian’s website and his email address, and after a few days of nerving myself up, I wrote to him. And he wrote back! I discovered that he was affable and gracious, and patient with my fanboy gushing through several emails (which, yes, I still have copies of) and offered kind words of encouragement toward my literary ambitions.

Plus? He’s a Fields of the Nephilim fan! So, yeah. Brian’s always been one of my literary heroes. And I’m happy to say that he remains every bit as affable, gracious, and patient today as he was back then. He even gave me his blessing to use the title of one of his short story collections, The Convulsion Factory, as the name of a goth/industrial club in my forthcoming novel, Fiction. I was thrilled when he agreed to take part in my La legado vivo! series. I enjoyed the hell out of this interview, and I hope you do, too. And if you’re not familiar with his work, get familiar with it. You’ll thank me, I promise.

Ryan Lieske: Brian, it is truly an honor to have this chance to discuss your Reading Life. For the uninitiated, why don’t you tell the readers about yourself and your work.

Brian Hodge: Brian Hodge accepted his destiny as a writer early, when as a preschooler he used to scribble on scraps of wood and affix them to unsuspecting trees. Eventually he learned the alphabet, which proved to be an enormous help.

He is now the award-winning author of eleven novels spanning horror, crime, and fantasy; over 125 shorter works; and five full-length collections.

Recent and upcoming works include his latest novel, Dawn of Heresies; I’ll Bring You the Birds From Out of the Sky, a novella-length cosmic horror + folk art combo platter; and his latest collection, The Immaculate Void, coming in early 2018. Two recent works are in the process of being optioned for feature film and a TV series, respectively.

He lives in Colorado, where he also likes to make music and photographs; loves everything about organic gardening except the thieving squirrels; and trains in Krav Maga and kickboxing, which are of no use at all against the squirrels.

RL: Hey, you never know. Haven’t you seen The Food of the Gods? Oh, and speaking of Krav Maga—I remember you posting about it on Facebook. And I just want to say congrats on going through that. That shit is no joke, and I would never have the fortitude to try it. Were I wearing a cap right now, I would doff it to you.

BH: You wouldn’t have to. I could kick it off your head. No, wrong attitude. It’s a path. I’ve practiced Krav for over eight years, with time off for wounds and injuries. I have no hesitation in saying that it’s had a beneficial impact on every aspect of my life.

RL: Well, still…if I do ever get the chance to meet you in person, I will gladly let you kick the hat off my head. I once someone knock an unlit cigarette out of my mouth with a bullwhip. Just saying. I like being the “volunteer from the audience.”

Anyway, on with the show. What is the first book you remember reading, or having read to you?

BH: I can’t pin that down. It might have been a Christmas-themed Little Golden Book. Or maybe one of these books about the adventures of a rabbit and a hippo, named Tinker and Tanker, that I liked.

RL: Do you recall the books that sealed your fate as a lifelong reader?

BH: There was never a turning point involving particular books. It just got baked in really early. I got a public library card when I was very young, and loved going there, heading up the stairs to the children’s floor, seeing the librarians. And Mrs. Buck, the librarian at my grade school. So it never came down to specific titles. It was upbringing and habit and, out of that, identity: I’m someone who reads. I’m someone who wants to always keep learning, and that means reading.

RL: I love that. I had a similar revelation as a child. It didn’t crystallize until a friend of mine said to me one day, “Man, you sure do love books.” And I loved hearing that, for some reason. Like, I didn’t feel like a “dork” or whatever it was he was implying by the comment. Though I wouldn’t have been able to express it this way back then, I see now that it was like a badge of honor. I was proud, and felt like a belonged to an exclusive group of people. I’ve never looked back.

BH: Yeah, there can be a bit of a freak flag about it. Right after I sold my first novel, Oasis, I went to go celebrate with a couple of my best friends, brothers, in northwest Alabama. I’d been there about an hour when Clark dug into a brand new story of mine I’d brought, and Brooke wanted me to read this alternate screenplay draft of Dawn of the Dead, and I forget what he was reading. After a bit of too much ominous quiet, their Dad looked in on us. He had this perfect Southern Gentleman accent. I’ll never forget how he cocked his head at us, like he couldn’t quite wrap his brain around the sight, and said, “Y’all are the readin’est folks I ever did see.”

RL: A lot of people tell me that, even if they were a voracious reader as a child, it was their middle-school and high-school years that had the most impact on the reader they are today. Would you say this is true for you?

BH: Not true for me. I read so much more broadly now than I ever did in junior high and high school. Looking back, I don’t see any key foundational significance to those years.

RL: Speaking of this time period, were you one of those kids who went rogue from the curriculum and read whatever you wanted, sometimes even ignoring what was assigned to read altogether?

BH: It wasn’t an either/or thing for me. It was both/and. I was a conscientious student, so I read what was assigned, and on top of that read whatever I wanted.

RL: Reading is inherently a solitary activity, so did your reading life ever supersede or cause conflict with your social life growing up? Were you more apt to hide out in the library at school, or stay home on a Saturday night to read a book?

BH: Those scenarios, not so much. But I was the type to take a book to family gatherings and self-sequester off to one side. “How was your Christmas?” “Great, I spent the day with Lucifer’s Hammer.”

RL: I recall one Christmas spent at my grandmother’s house, immersed in Stephen King’s It, and my older cousins kept making fun of me for “trying to a read a book that big.” I knew nothing of creative retorts back then, so I imagine I spent most of day scowling.

BH: At least a book that big makes for a great bludgeon, if you decide to get your inner Jason Bourne on.

RL: Damn it. If only I could go back in time. 16-year-old me might’ve led a completely different life. Or, not. Probably not.

What new books, literary styles, or genres were you exposed to in college? Out of those, what stuck with you? How did they change you as a reader, and what type of books you started to seek out?

BH: One course I took—I think it was actually a psychology course, something like Literature And Madness—steered me toward books I might never have been in any hurry to get to. Russian classics like Crime And Punishment and Notes From Underground. Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, and Joyce Carol Oates’ Them, which was my first exposure to her.

But the biggest milestone from then came out of just another typical afternoon bookstore run, when I found Kirby McCauley’s landmark anthology Dark Forces. That introduced me to so many writers doing the kind of things I hoped to do, and at a state of the art level. It was also what gave Clive Barker the conceptual framework for The Books of Blood. He wanted to encompass its breadth and depth, but coming from a single author instead of twenty-four.

RL: I’m ashamed to admit this, but, though I know both books, I’ve never read Dark Forces. Have you gone back to it?

BH: I kept Dark Forces handy for a lot of years, but my copy eventually got boxed away somewhere for some move and has been in extended hibernation ever since. I’m sure if I were to unearth it, I’d find that it’s aged well.

RL: What were your first bookstore experiences?

BH: I remember a couple. There was this bookstore in a big old house a couple blocks away from my junior high school, and I would often run down there during lunch hours, solo or with a friend. It was in business less than a decade. Then there was this news and hobby shop that had books, comics, and model kits, so it catered to the geek in me on multiple levels. I don’t know if that’s still there. It was around forever, but was in a place I left nearly twenty years ago, and even then, the downtown was withering, so I don’t hold out much hope for it now.

RL: Did you find, as you grew older, that the books of your youth began to mean less to you?

BH: It’s normal to outgrow certain things. That bookstore near my junior high? It was where I discovered Don Pendleton’s Executioner series, and I was big into that for a few years, but I’ve never had any desire to revisit them. And, on a much higher plain, I’ve heard people say that around that age is a great time to discover Kurt Vonnegut, but you could never return to him as an adult with the same impact. Nothing makes me cringe, though. Even if it wasn’t very nutritious, it fed the habit and kept it alive.

RL: I completely agree. Although I’ve never heard that about Vonnegut. I still enjoy his books. Although, admittedly, they don’t give me the same feeling as they did when I was younger.

BH: I think that’s all the person was saying: Read him anytime and he’ll still be wonderful, but there’s this window of maximum impact.

RL: Ah, gotcha. That makes sense.

How has your reading life survived adulthood? I talk to a lot of people now who “wish they had more time to read, but can never find the time.” Is this a problem you face now?

BH: “Find the time” … there’s the issue, the way that’s framed. Nobody habitually finds time lying around without some kind of claim on it. “Look at this, somebody left a big bagful of hours just sitting here.” No, never happens. When something’s an elective rather than a requirement, or isn’t breathing down your neck with a sense of urgency, you either make time for it or you don’t. And you might have to fight like a motherfucker for that time, whatever you want it for. Myself, I treat reading as a priority, and regard it the same way I do working out: that one way or another, it’s time that pays for itself.

RL: I love that. I’ve never heard it put that way before, but damn, that is perfect. I, too, make it a priority. My writing (be it screenplays or fiction) suffers whenever I slack off on my reading regimen. Do you feel that way?

BH: I don’t think my work suffers, but overall, I feel less whole. Maybe there would be actual atrophy if I let it go on long enough, but I seem to course-correct before then.

Anymore, I approach reading strategically instead of the haphazard way I used to. Going into each month, I’ll have a list of books to tackle, ideally a 50/50 split between fiction and nonfiction. A few novels, plus an anthology or a collection. With the nonfiction, it gets divided among research, courses of self-study, topics I’m interested in, and things that might help me live better, or optimize health, fitness, mind, body. I always make room for what I think of as useful books. This year I’ve been on a biohacking thread, after seeing last year how effectively I was able to hasten the recovery and rehab process following a stupid accident that required knee surgery.

RL: I, too, do the 50/50 split, too. I usually go with something I’m researching, and one on a topic I happen to be interested in. Fiction is divided between one “literary fiction” book and one “genre book.” Although, if the subject I’m researching is more than one book can contain, I’ll pretty much drop everything and immerse myself in that until I’ve got all I need.

BH: Sometimes my best-laid plans fall apart, too. Shiny Object Syndrome.

RL: What was that? Sorry, I missed what you were saying. My cats were wrestling.

Anyway, I’m not a big fan of the term “guilty pleasure.” However, for want of a better term, what are your literary guilty pleasures?

BH: I don’t have the mindset that classifies things as guilty pleasures, either. We like what we like, so why feel that we really shouldn’t, or have to justify it to ourselves? It’s a waste of perfectly good shame.

RL: Ha! Amen! I have plenty of other things to be ashamed of, so I don’t give a damn what anybody thinks about the books I’m reading or movies I’m watching. Although if you ever catch me reading a Nicholas Sparks novel, please put me out of my misery. I’ll leave a note for the police absolving you of any crime.

BH: You might be surprised. Not that I can speak to Sparks one way or another, but years ago, when it was pretty much inescapable, I decided, okay, I’ll read The Bridges of Madison County, it won’t take long. And I was surprised. A little mawkish here and there, but it was a far cry from what most detractors were making it out to be.

RL: That’s a good point. My mother, who lives on a diet of strictly Christian fiction, told me I should read The Shack, so reluctantly I did. It was by no means a revelatory reading experience, but I did appreciate its surprisingly subversive take on Conservative Christianity. You know, “Church isn’t a physical place, it’s a state of mind.” I could dig that. I also read that book about Dewey the library cat, and I completely bawled my eyes out at the end.

I love cats. Leave me alone.

I love cats. Leave me alone.

Now, this one could apply to all art, really, but in terms of writing, what are your thoughts on “genre?” Ultimately, do you think genre labeling even matters? Does it matter to you?

BH: It’s a double-edged sword. I’ve known zero people who want to walk into a book or record store, or browse a streaming video service, and find it’s laid out with the A’s up front, Z’s in the back, and no further subdivisions in between. So if you’re predisposed to a particular kind of book or music or whatever, genre designations make them easier to find. But labels can be limiting, too, both in terms of giving an accurate expectation of something, and what audiences may be prepared to let you get away with mashing together as a creator. Not everything fits into neat cubbyholes. But I’d rather have the labels, to find as well as be found, and sometimes chafe against them, than not.

RL: Very good point. Whenever anybody asks what kind of book mine is, I’ll say, “It’s horror. BUT, it’s also…” I’m always worried that word will turn some people off. But I’m getting over that. It probably has roots in high-school and college, where certain teachers and profs would turn their nose up at me and say, “You should really get out of this ‘horror phase.’” And it’s unfortunate, because they don’t seem to realize just how broad “horror” can be. I mean, I consider Beloved a horror novel. The Road, Lord of the Flies, Macbeth—all “horror” to me.

BH: Which recalls critic Douglas Winter’s eternal contention, that it’s not a genre, but an emotion.

RL: Words I live by, and write by. Our mutual friend, the late Philip Nutman, and I used to discuss that all the time.

Are you a physical copy person, or do you prefer other ways of “reading” books, such as e-books or audio? Does the “delivery system,” as King calls it, matter to you? And while we’re on the topic, what do you think the future holds for reading? Do you think physical books will always be available?

BH: I’m fairly platform agnostic. I’ll always prefer the tactile experience of physical books, but I happily use the iBooks and Kindle apps on my iPad, too, and spin the occasional audio book.

I don’t expect to see physical books disappear in my lifetime. They seem pretty tenacious about hanging around. A few years back, when e-books started becoming viable, there were people very self-assuredly predicting the imminent demise of this archaic paper-based technology, but I couldn’t take them seriously. My reaction was more like, “Really. Tell me more, you with your tech blog and your twenty-three whole years of life perspective.” And sure enough, e-books have more or less plateaued without supplanting anything. People just like the epicurean pleasure of holding a book.

I felt that I’d seen this before, with music-making technology, synthesizers in particular. It may seem like an odd comparison, but the parallels are there. When digital synthesis first came along, the widespread reaction among musicians was, “Great! Now we can ditch these bulky old analog synths.” Then, in time, it was, “Hey, remember how awesome analog synths were? How good they sounded, how much fun the knobs were to interact with, compared to this panel of membrane switches and a data slider?”

Later, after computers were powerful enough to run them, and the coding got mature enough so they really started to sound good, software instruments were supposed to be the death of hardware. Well, that was bullshit too.

It all co-exists side-by-side now. Every market is probably as robust as it’s ever been. Even modular synthesizers have seen a huge renaissance, and that’s hardcore. But nothing went extinct as a product class. Which is how I’ve always expected to see books and their delivery systems continue.

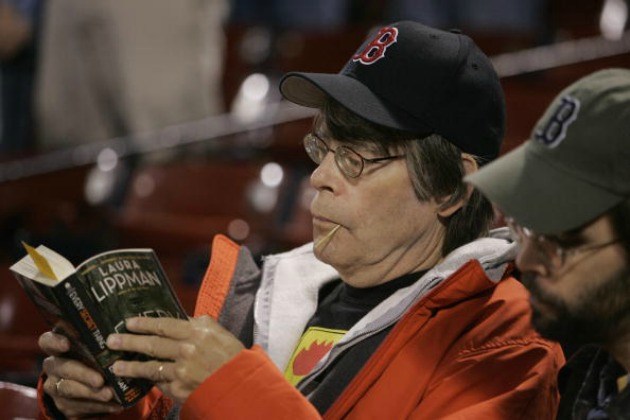

RL: Speaking of King, he’s often been seen at baseball games reading a book during rain delays or between innings. Says he never goes anywhere without a book. Do you take a book with you wherever you go?

You may be cool, but you’ll never be Stephen King reading at a Red Sox game with a toothpick in his mouth cool.

You may be cool, but you’ll never be Stephen King reading at a Red Sox game with a toothpick in his mouth cool.

BH: Pretty much, yeah. Someplace like the grocery store, I know I’m going to scoot through quickly, but if I’m heading someplace where there’s any chance of delay or downtime, then yes, I want options. Like when we were little and our parents had to bring along coloring books to keep us from humiliating them.

RL: I’ve actually been late for doctor’s appointments because I had to turn around and go back home to get a book. One time my dentist let me read a book while he was cleaning my teeth. I don’t know if this is problem, but I don’t really care.

BH: Problem or not, that’s dedication. Didn’t the pages get speckled when he broke out the rotary brush?

RL: Yes, actually. But I was riveted to that book, man. It was Joyce Carol Oates’ Zombie, so a bit of speckling seemed strangely apropos.

Try it. Your dentist will love it.

Try it. Your dentist will love it.

So, we come to the almost-impossible-to-answer question: What are your favorite books of all time, and why?

BH: I always have trouble answering questions like this the way they’re intended. I don’t think of books in quite the same way as I do, say, favorite albums, because I’m not experiencing them over and over again for years or decades.

I think more in terms of favorite reading experiences. There’s a distinction. It’s when you read the right book at an ideal time, and there’s a synergy about it that leaves you able to remember where you were and what else was going on. It might be so clear you can recall yourself in a specific location reading specific passages.

The first one to hit me that way was Glendon Swarthout’s Bless the Beasts & Children. In seventh grade, I was put in this experimental, accelerated, academic program, where we had our own house instead of a classroom, and my closest friends there and I passed around the same copy. It wasn’t assigned, we were just into it, and related to this set-aside group of boys in the book, so it was a genuine communal experience.

Stephen King’s The Stand was another. I read a lot of that on a spring break trip to Florida, so it became an experience with multiple layers of journey. I was enthralled by John Irving’s The World According to Garp, which I read within the first year of getting serious about my own writing, so again, there’s that life/page resonance.

Barker’s The Books of Blood, especially those first three, were a revelation, like seeing a bar get raised right in front of your eyes.

RL: Yes, those first three volumes changed my life. I read them in high school, just as I was beginning to take my writing ambitions seriously. I had read plenty of King at that point, so he was my first real influence on the stories I was producing, but the Books of Blood—yeah, I could almost see the rules changing before my eyes. They unhinged my imagination and showed me that the possibilities of “horror” were limitless.

I had a similar experience reading Kathe Koja’s Bad Brains the first time. I was 18, my girlfriend at the time had just broken up with me, and I was wallowing in self-pity like you wouldn’t believe. So, I bought Bad Brains, and started reading, hoping to take my mind off what had happened to me. That books is not the book to that. But, fuck, that book seemed to speak directly to me at that moment. It wallowed with me, and took me to an even darker place than the one I thought I was in. And it completely changed the way I approached character and character development in my own work. So, yeah, I can totally see what you’re saying. I re-read the book years later, and it didn’t have that same gut-punch effect, though it remained a powerful reading experience.

A couple of years after that, I had the same experience when reading your novel, Prototype, and your story collection, The Convulsion Factory. The idea of taking my own psychological and emotional pains and giving them to my characters, which had been engendered by Koja’s work, was galvanized by reading yours. While Barker and King inspired me to write, I credit you two with teaching me what I wanted to write. I wanted to explore the darkest depths of the mind and the soul, which those books taught me to do. Those are some dark, dark books. Edward Lee called Prototype a “psyche-wrecking work of art.” I’ve often been told that my work is “dark and unsettling.” And I thank you and Koja for that. Or blame you for that…nah, I’ll go with thank you.

BH: You’re very welcome. It’s a heavy burden, the responsibility for someone’s upbringing, but I’d say we done good. And you should like this: I got to read Kathe’s debut novel, The Cipher, a few months early, when our mutual editor, Jeanne Cavelos, sent me a proof copy. When I finally met Kathe that spring, about the first thing I said to her was, “I loved it. You ruined Christmas.”

RL: Well, if Barker and King were my parents, Kathe and you were my older brother and sister who helped me sneak into my first R-rated movie and let me stay up late watching the movies I wasn’t supposed to be watching. If that makes sense. Anyway, I definitely thank you for guiding me down the right path. I have a few scars—internal and otherwise—but I doing just fine. And you know my inner fanboy is totally jealous of you right now, getting to read Cipher early.

Young people: whenever you’re feeling hopeless, read this book. Trust me, it will make you feel better.

Young people: whenever you’re feeling hopeless, read this book. Trust me, it will make you feel better.

I’m obviously really intrigued by these experiences that you’ve talked about so far. Are there any others you could mention?

BH: There are several more like that. And a series can do it to you, too, not necessarily on the strength of one book, but by their cumulative weight. Right now, there’s probably nothing I look forward to more than each new novel in Bernard Cornwell’s Saxon Tales series, which take place during the unification of England from separate kingdoms into a single country. I’ve been reading those for a decade. In the new one from earlier this year, something finally happened that I’ve been waiting for through ten novels, and it was soooo satisfying.

RL: What books―and they don’t have to necessarily have to be “all-time favorites”―do you feel have influenced you and shaped you the most: as a human being, as an artist, etc.?

BH: The writer side of me doesn’t find that level of influence as having come from key books so much as individual writers across multiple works. And, while it was never a remotely comprehensive list, I used to name whoever occurred to me at any given time. But I’ve decided not to do that anymore. We’re in a climate now where that’s less a useful answer for anyone and more a needle jab for outrage junkies to get their next fix, that no matter who you credit, it’s not good enough, you haven’t been demographically inclusive enough to suit them.

With nonfiction, the big impacts tend to come from books that change the way I do things, or help me be more effective in getting to more of what I want to do and be. Some of the vital ones in the past few years are The Power of Full Engagement (Jim Loehr and Tony Schwartz), The Accidental Creative (Todd Henry), and all of Tim Ferriss’ stuff is great, highly actionable.

RL: Okay, so what are some of the worst reading experiences you’ve had?

BH: To me, the worst reading experiences come when you have every right to have expected better, so bad work gets compounded by disappointment. Back when I was writing reviews for David B. Silva’s Hellnotes newsletter, I covered a couple that stand out for the worst reasons.

One was Thomas Harris’ Hannibal. I recalled The Silence of the Lambs as being dark and precise, but this came off like he’d had a decade to get bored with his own material, and was struggling to maintain his interest, by injecting this ridiculous, gaudy, ham-handed, over-the-top stuff. A report at the time said that the novel was rushed into print after he delivered it without anyone knowing it was coming, and that by contract he was able to eschew editorial oversight. That’s usually a red flag that the writer’s ego has gotten in the way of serving the work, and it showed. Which was too bad, because there was a sequence of fifty or so pages that was superb.

The other was Ira Levin’s Son of Rosemary, which might be the laziest book ever written. It was astonishingly wretched. There was no sign at all of the Ira Levin who wrote works like A Kiss Before Dying and The Stepford Wives. His acknowledgments gave the impression that the novel piggybacked on a movie deal … a movie that was apparently never made. Levin thanked producer Alan Ladd for getting him off the couch. He should’ve stayed there. The novel didn’t just shit all over itself. At the end, it turned around and pissed all over Rosemary’s Baby, too.

RL: You are the second person I’ve interviewed to cite Hannibal. The other was Elizabeth Massie. Strangely enough, I actually liked Hannibal when it was released, and I railed against the haters. I think Red Dragon and The Silence of the Lambs are brilliant. But as the years pass, I’m starting to wonder if I only liked Hannibal out of spite. Thing is, I don’t really feel any inclination to go back to it and find out. Come to think of it, that probably tells me what I need to know.

BH: If you have fond memories of it, no need to torpedo them. But there’s another possible backstory to this. I’ve just seen, for the second or third time, the contention that this was a novel Harris didn’t actually want to write. That he’d started one that didn’t involve the character of Clarice Starling, but he needed the money and couldn’t turn it down when, in the wake of the Lambs film success, through some combined book-movie deal, he was offered a lot to bring her back. Then wrote what he wrote as a fuck-you to all concerned. Or maybe he genuinely tried but his heart wasn’t in it, which goes back to my original observation that he appeared to be struggling to maintain his own interest. Either way, I do recall seeing that when Lambs director Jonathan Demme and Jodie Foster saw what they would have to work with, they bailed, they wanted no part of it. And, as a reader, I’ve never gone back to him.

RL: Now that you mention it, I seem to recall hearing all that. I think I’ll just let sleeping cannibals lie and move on. I did hate the film version of Hannibal, and I refuse to read Hannibal Rising, because I don’t want that character demystified for me.

Well, Brian, Thank you for discussing your reading life with me. Looking forward to your upcoming work! Cheers!

Brian’s “reading face.”

Brian’s “reading face.”

Find Brian Hodge and his work online:

Official Brian Hodge Website

Brian Hodge on Facebook

Brian Hodge on Twitter

Share this: