readinggass.org

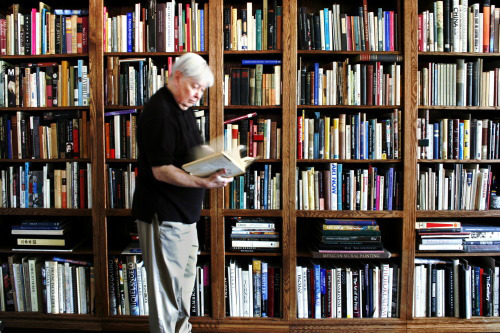

William Gass died Wednesday. He was 93. His wife, Mary, told the St. Louis Dispatch that he continued working on projects through the autumn. Incredible. Gass was a remarkable writer and a High Modernist master. He published three novels, three collections of short fiction, and seven collections of essays, in addition to the thirty years he taught philosophy at Washington University in St. Louis, during his life.

David Foster Wallace made me aware of William Gass during my reading of his posthumous collection of essays, Both Flesh and Not, when he described Omensetter’s Luck as “bleak but gorgeous, like light through ice.” His description of Gass’ first novel applies to much of his fiction. Bleak but gorgeous. Gorgeous prose about bleak lives, bleak landscapes, bleak minds, bleak moods, bleak conditions, bleak history. He wrote prose as good as Joyce, James, and Nabokov, musical prose, serpentine prose, prose one could admire. He liked to diagram Gertrude Stein’s sentences. He celebrated the sentences of Henry James. The sentence, for Gass, was a container of consciousness. Gass used to write the same sentence in different ways. He told The Paris Review in an interview that he “sat down with the greatest deliberation and thought how I would make each letter of the alphabet from that moment on.” For some time he wrote in a hand “very Germanic and stiff” which, he admitted, later dismayed him because it was like so much “strands of barbed wire.”

Gass was a writer’s writer. He thought hard and deeply about the act of writing, the physical act of putting pen/pencil to paper, and he spent a long time writing and composing his fiction. The Tunnel took close to thirty years of work. A colleague stole the first Omensetter’s Luck manuscript, so Gass rewrote the whole thing, and in re-writing the novel Jethro Furber emerged as its hero, or antihero, because he had the rhetoric. Middle C took thirteen years. Gass rejected traditional narrative. Him and John Gardner had a famous debate about fiction in which Gass said, “But what I really want is to have it sit there solid as a rock and have everybody think it is flying” after Gardner criticized his fiction as being “too encrusted with gold to get off the ground.”

Readers loved his essays more than his fiction. MJ Nicholls, a prolific Goodreads reviewer, succinctly captured the brilliance of Gass the essayist:

“Imagine being the editor of a respectable literary publication (if it helps, quote FR Leavis and take up chronic alcoholism) and receiving a book review from William H. Gass. Not only has he written the best review of a marginal publication unworthy of his masterly talents that no mortal will ever read, he has also written a scholarly essay bursting with philosophical insight, twenty pages of sumptuous pedantic analysis, and a wonderfully rich encapsulation of the author whose work is being discussed.”

His essays and criticism were unlike any essays and criticisms published in mainstream publications, whether in print or online. They could be long, digressive, erudite, esoteric, challenging, and difficult, and not all readers appreciated going into the weeds of sentence ontology, structure, and some found his alliteration tiresome and overused, but, for me, reading his essays jolted my mind. I could see how deeply one could tunnel into a work, a chapter, a paragraph, a sentence, and a word. Criticism seemed empty, dull, and unimaginative after reading a Gass essay about Calvino’s Invisible Cities or his introduction to Gaddis’ The Recognitions or his introduction to Rilke’s Auguste Rodin. My paltry reviews couldn’t compare to his monolithic introspections and analysis. He was a better, smarter reader than me.

Gorgeous cover art

Obituaries have credited him as the inventor of the word ‘metafiction’, a word he used to describe, among others, Flann O’Brien’s At Swim Two Birds. Metafiction, to him, was writing “in which the forms of fiction serve as the material upon further forms can be imposed.” He experimented in every work of fiction. “The Pederson Kid”, his first short story, was composed in 1951 and not published for nine years. In 2013, Gass told an interviewer that literary magazines rejected his stories because they didn’t understandwhat they had read. One of his stories in his last story collection, Eyes, was written from the perspective of the prop piano Sam plays in Casablanca, and another, from the perspective of a folding chair in a barbershop. His Cartesian Sonata features “Emma Enters a Sentence of Elizabeth Bishop”, a long story about one sentence/line from an Elizabeth Bishop poem. Gass wrote about verbal consciousness in an essay on Emerson years ago. The kitschy clutter in his story “Bed and Breakfast” make up its verbal consciousness. You’ll notice that his fiction begins and ends with language. A story is words written on a page.

My examples only show the surface of his experimentation. He eschewed narrative to experiment with form and structure. He told Michael Silverblatt in a 1998 interview that “since I don’t generally have a structure that even resembles plot or story or something–there’s usually something there, of course; you can’t eliminate it all together–but what I prefer to work with are themes and symbols and moods and conditions.” Musical structure forms the structure of his last two novels, The Tunnel and Middle C: a fugue structure for The Tunnel, similar to the fugal structure in the “Sirens” episode of Ulysses, and a Schoenbergian structure in Middle C. He imposed other structures on top of those aforementioned structures (“sections within sections…it’s sectioned up like an insect or worm). The Tunnel has twelve chapters about the same length, and each section becomes part of the tunnel Kohler digs in his basement. The problem of a sentence forms the overall structure of Middle C.

Gass wrote fiction I dream to write, fiction which I’m not gifted enough to write and sustain. My unpublished short novel has a minor character, a professor, a High Modernist, partly inspired by Gass and a philosophy professor at the Community College of Philadelphia, who wrote a 1200 page manuscript in which the central chapter spans a hundred pages or more about the fall of a single leaf from a tree, and I gave my character that book because it is something I could not write. It is an unpublishable and unreadable book my Professor Bok wrote, but deep, immeasurable in its depth, and gorgeous I would’ve loved to write “Bed and Breakfast” and “Emma Enters a Sentence of Elizabeth Bishop”, and I’m grateful William Gass did, because I never could. The Tunnel is an extraordinary masterpiece, a titanic literary achievement, only equal, for me, with Ulysses in its depths, genius, and linguistic virtuosity.

I read On Being Blue first but my heart was set on reading The Tunnel, which I did read during the autumn of 2014, along with Omensetter’s Luck. Bleak but gorgeous reads. I moved on to In The Heart of the Heart of the Country in early 2015. I read “The Pederson Kid” during a snowstorm. I read the entirety of “The Master of Secret Revenges” during my cross-country flight from Los Angeles to Philadelphia in March 2015; “Emma Enters a Sentence of Elizabeth Bishop” during delays in LAX; “Bed and Breakfast” in a hotel room in San Francisco; Middle C later in 2015; and Eyes last year. All of which I returned to here and there to re-read parts or the whole of whenever I needed to remind myself of the enormous capabilities of the written word, or whenever I wanted to re-enter a world of his to savor one of his sentences, and all of which I’ll continue reading for years to come, because, though I love and admire what he wrote, I feel I still have much to learn and understand about it.

Rest easy, Mr. Gass.

Advertisements Share this: