Francis Crick opened his book The Astonishing Hypothesis with this salvo:

Q: What is the soul?

A: The soul is a living being without a body, having reason and free will.

—Roman Catholic catechism

The Astonishing Hypothesis is that “You,” your joys and your sorrows, your memories and your ambitions, your sense of personal identity and free will, are in fact no more than the behavior of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules. As Lewis Carroll’s Alice might have phrased it: “You’re nothing but a pack of neurons.” This hypothesis is so alien to the ideas of most people alive today that it can truly be called astonishing. (p.3)

A lovely statement, but did Crick really mean it? Your mind, your conscious perception of the world is nothing but neurons? This is reductive materialism with a vengeance. He goes on to say “It does not come easily to believe that I am the detailed behavior of a set of nerve cells, however many there may be and however intricate their interactions.” (p. 7) Nothing more? It would mean that there are no immaterial mental states—only neurons. Your joys and sorrows etc do not exist. That’s not actually what Crick has in mind.

Sometimes people claim to be materialists in this strong sense, claim to believe Crick’s astonishing hypothesis, but what they really believe is simply that there is no soul without a body, contrary to the catechism. Chapter 2 of Crick’s book is entitled “The General Nature of Consciousness.” But didn’t he already tell us that the general nature of consciousness is “no more than the behavior of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules”? What more is there to say? There would be plenty of details to work out about the behavior of neurons, but nothing more to say about consciousness, which does not otherwise exist.

What Crick and most other materialists really have in mind is that consciousness is caused by the brain, that brain states are correlated with mental states, and that the mind cannot exist without the body. Minds do not float free of brains. The slogan is “no [mental] change without a physical change”. An exact physical duplicate of your body would be enjoying the same mental events you are. That’s enough to refute the catechism. However, consciousness—your joys and sorrows, your memories and ambitions, etc—still exists. The goal of neuroscience is to find NCCs—neural correlates of consciousness. “This useful term is worth committing to memory” he says. (p. 9) This commits neuroscience to a form of dualism and would refute eliminative materialism, contrary to the astonishing hypothesis.

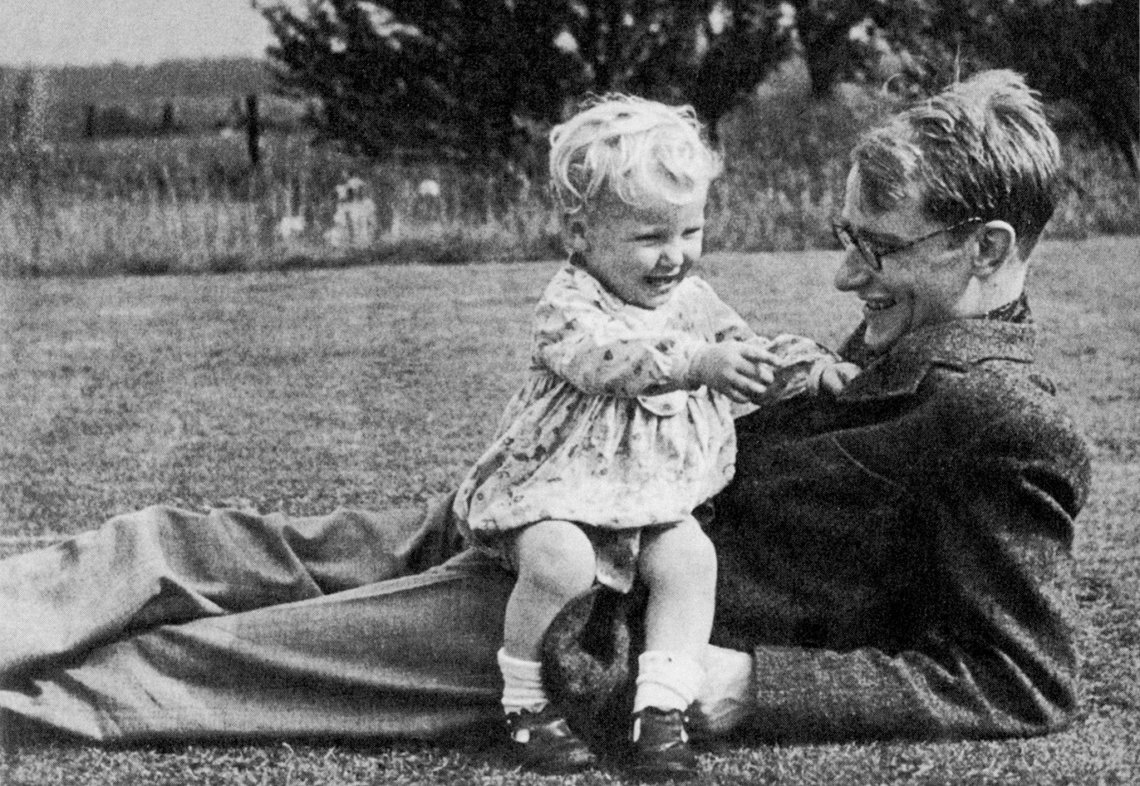

Crick was the co-discoverer of DNA with James Watson in the early 1950s. By the 1990s, he was working in neuroscience with Christof Koch. Here’s how Koch described that work in the 2000s:

Consciousness is a puzzling, state-dependent property of certain types of complex, biological, adaptive, and highly interconnected systems. A science of consciousness must strive to explain the exact relationship between phenomenal, mental states and brain states. This is the heart of the classical mind-body problem: What is the nature of the relationship between the immaterial, conscious mind and its physical basis in the electrochemical interactions in the body? Brain scientists are exploiting a number of empirical approaches to shed light on the neural basis of consciousness. http://www.scholarpedia.org/article/Neural_correlates_of_consciousness

Koch is explaining the science of consciousness as a relation between two things: #1 phenomenal mental states, the “immaterial” conscious mind, and #2 brain states, the electrochemical interactions in the body. The idea of neuroscience is to address the classic mind/body problem by finding correlations between #1 and #2. Those would be the Neural Correlates of Consciousness— NCC— defined as the minimal set of neuronal events and mechanisms sufficient for a specific conscious percept. This is good and valuable work, which Koch started with Crick, and has continued after his death in 2004.

The premise of the science of consciousness is that you are not just neurons. Your joys and sorrows, you memories and ambitions, your sense of personal identity and free will are all phenomenal mental states to be correlated with specific types of neural activity. If you are nothing but neurons, this scientific project makes no sense. What is there to correlate the neurons with? Neuroscience has a fundamentally dualistic outlook, not at all the eliminative materialism Crick seemed to be suggesting. Yet nobody in science wants to claim dualism and few in philosophy like it either.

Francis Crick with his son, Michael, around 1942:

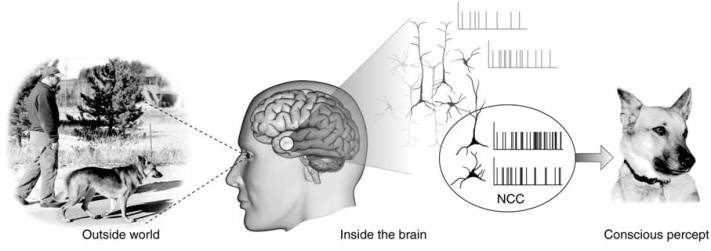

Koch has a fascinating diagram:

The Neuronal Correlates of Consciousness (NCC) constitute the smallest set of neural events and structures sufficient for a given conscious percept or explicit memory. This case involves synchronized action potentials in neocortical pyramidal neurons.

The Neuronal Correlates of Consciousness (NCC) constitute the smallest set of neural events and structures sufficient for a given conscious percept or explicit memory. This case involves synchronized action potentials in neocortical pyramidal neurons.

In Koch’s diagram, causation moves left to right. Light reflected off objects in the Outside World contains useful information. Your eyes transduce that information into neural impulses. “The arrival of photons on the retina is transduced thanks to rhodopsin in the rods and cones, to yield spike trains in the optic nerve.” (Dan Dennett) The spike trains travel to the brain for processing of the information. The bar codes in the diagram represent the information, here shown at a level of abstraction. Some neural processes have the capacity to cause the Conscious Percept—those are the NCCs. The arrow on the right shows this physical to nonphysical causation. You have a conscious visual experience of the dog. In full living color. The dualism is shown by having two dogs in the diagram—one in the outside world and another in your conscious percept. One is the real material dog, and the other is dog as experienced, which is immaterial.

All this is straightforward and makes a lot of sense, at least at first glance. How else to conceive of what happens in perception? It seems like nothing more than scientifically enlightened common sense, although philosophy has been struggling with this schema since the 17th century.

About his diagram, Koch has this to say:

Consciousness is a puzzling, state-dependent property of certain types of complex, biological, adaptive, and highly interconnected systems. A science of consciousness must strive to explain the exact relationship between phenomenal, mental states and brain states. This is the heart of the classical mind-body problem: What is the nature of the relationship between the immaterial, conscious mind and its physical basis in the electrochemical interactions in the body?…

Progress in addressing the mind-body problem has come from focusing on empirically accessible questions rather than on eristic philosophical arguments. Key is the search for the neuronal correlates — and ultimately the causes — of consciousness…

Every phenomenal, subjective state will have associated Neural Correlates of Consciousness: one for seeing a red patch, another one for seeing grandmother, yet a third one for hearing a siren, etc. Perturbing or inactivating the Neural Correlates of Consciousness for any one specific conscious experience will affect the percept or cause it to disappear. If the Neural Correlates of Consciousness could be induced artificially, for instance by cortical microstimulation in a prosthetic device or during neurosurgery [or by Descartes’ evil demon], the subject would experience the associated percept.

Koch seems not in the least bothered that his science of consciousness concerns “the immaterial conscious mind.” Nor should he be. Nonphysical experiences are what cognitive science hopes to explain. There are two transductions in Koch’s schema. The first changes the information in light into neural impulses. The second transduction is represented by the arrow on the right of the diagram, showing NCCs are transduced into images in the immaterial conscious mind.

Everything you experience or could experience—your entire world as experienced—lies to the right of the arrow. This means that you never experience the Outside World directly, but only via the immaterial Conscious Percepts (qualia, or Bertrand Russell’s sense-data). The existence of the Outside World is based on an inference. “I’m having a dog percept, so probably—not certainly— there is a dog out there.” The percepts amount to evidence about what’s out there, not the world itself. Your percepts are private; nobody can experience them but you. If someone else sees the dog, they get their own Conscious Percept created for them by their own NCCs—not yours. Starting with Descartes, philosophy has spent a lot of time worrying about the implications of this picture.

Crick endorses a view he attributes to Dave Marr “that brain builds within itself a symbolic representation of the visual world, making explicit the many aspects of it that are only implicit in the retinal image.” (p.76) That would be, for example, the dog on the right. What you experience is not the real dog, but rather the symbolic representation built within your brain.

Share this: