Propaganda is only a paper tiger; paper books are the ones with teeth and oh! how they bite! Sijie’s novel shows the underbelly of China’s re-education program, its failure a fait acompli from the beginning.

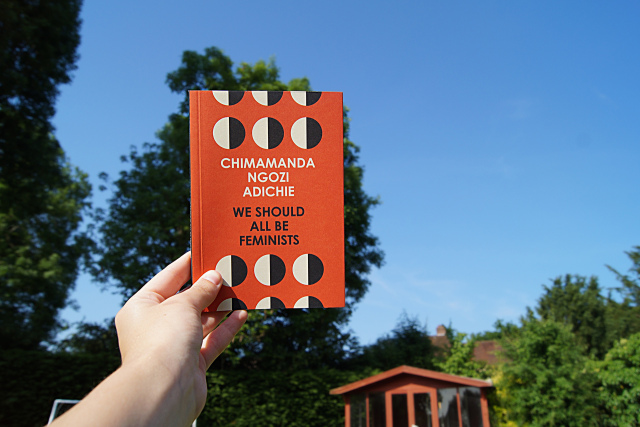

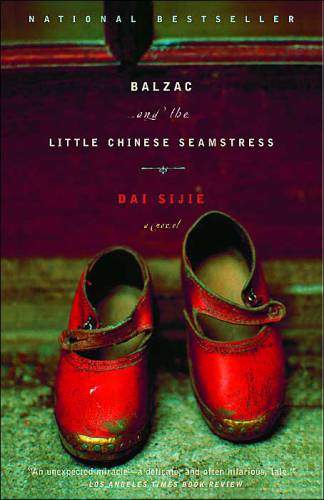

Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress · Dai Sijie

Ina Rilke translation · Anchor Books, 2001 · 184 pages, paperback

♠

The violin, its varnished wood smooth, reflects the embers. It fails to be a toy of the Western bourgeoisie when the sonata cut by its bow is given a new name: “Mozart is Thinking of Chairman Mao.” An enemy music made ally by a lie.

The village headman contemplates. Mozart is thinking of Chairman Mao? The violin may stay.

The Great Leap Forward was, of course, a Great Leap Backward, and in the same vein China’s re-education program was a mandate for ignorance.

More pernicious than full censorship or medieval blackout, the re-education program warped what was real, creating new false versions of what existed before the revolution. Re-education created a void, but it then filled this void with ridiculous tripe that could make the sycophants salivate.

China’s Cultural Revolution sent 17 million “up to the mountains and down to the countryside” between 1966 and 1976. Dai Sijie was one of them. His first novel, Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress, shows the futility of China’s re-education program and the sadness of his two protagonists’ three in a thousand chance of returning home.

♠

Sijie’s protagonist (unnamed) and his friend Luo are to be re-educated after their parents, highly regarded doctors and a dentist, are classed as enemies of the people for their successes before the revolution. They’re sent to one of the small mountain villages in the district of Yong Jing and are boarded in the house on stilts of the village headman, the same man who listened so distrustfully at first to the Mozart sonata.

The two friends meet the local tailor and his daughter, the Little Seamstress. They recognize an old friend from the city, also sent “up to the mountain,” though to a neighboring village.

The two find in their friend’s lodgings a suitcase full of books that are not Little Red Books.

Luo’s forbidden flirtation with the Little Seamstress is a measured courtship dance; its naturalness, its mature innocence, is in fundamental opposition to everything sanctioned by the regime, their trysts marked by readings of Balzac and oral retellings of Yong Jing films and by secluded lovemaking, secreted by the boughs of the gingko trees and a thin ridge that traverses chasms fathoms deep.

Under the gingko trees there are no slogans. Under the gingko trees there are no warped stories. Under the gingko trees no one is thinking of Chairman Mao.

Sijie’s prose is clean, spare, utilitarian. But his protagonist, as the novel progresses, as he reads each book in the suitcase, adopts an ease with metaphor and writes phrases more and more reminiscent of classic Western literature.

The ending of Sijie’s novel is thematically cathartic and shows how books became an inflated currency during China’s revolution. His novel comes full circle, ablaze with a final sting that underscores the force of literature.

♠

Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress · Dai Sijie

Ina Rilke translation · Anchor Books, 2001 · 184 pages, paperback