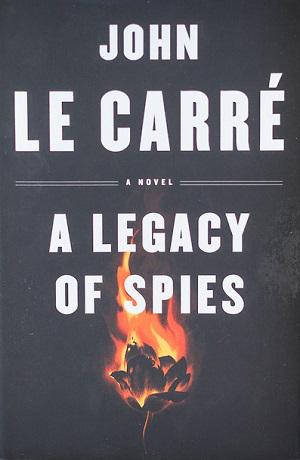

John le Carré

A Legacy of Spies

(Penguin Viking, 2017)

Not so long ago, I was lunching with a former City analyst, someone with whom I’d knocked about during the turbulent financial and economic events of the late 1980s and early ’90s, when the phone lines between Fleet Street and the Square Mile were running red hot. We reminisced about those days: Big Bang, the Lawson Boom, Black Wednesday, as well as the long-forgotten bits of furniture, such as Sterling M3, the ERM divergence indicator, and the Ken and Eddie Show.

‘Isn’t it funny,’ he asked, ‘how we thought all of that actually mattered?’

John le Carré’s latest is permeated by a similar wondering as to the priorities of yesteryear, a sense of chapters closing (no pun intended), of TS Eliot’s ‘burnt-out ends of smoky days’.

The central character is ex-MI6 agent Peter Guillam. To some of us he will always be as portrayed on television by a youthful Michael Jayston, but here he is retired and living in rural France. Out of the blue, he is summoned to London to be grilled as part of a secret service investigation into a botched operation in the early Sixties, the plot of le Carré’s 1963 novel The Spy Who Came in from the Cold.

For the uninitiated, Alec Lemas, a high-up in MI6’s Berlin station, pretends to defect in order to testify falsely that a senior East German intelligence officer is a British spy. So cack-handed is the smear attempt that the officer is cleared, at which point Lemas realises that the Circus (le Carré-speak for British intelligence) has played a very clever game. The man is a British agent but, thanks to Lemas, will now never be suspected. Furthermore, his rival and chief accuser inside the East German service, Fiedler, the one the British were really worried about, is now condemned as a traitor and probably executed.

Alas, the Circus failed to appreciate their East German agent’s ruthlessness, and he has Lemas and his girlfriend shot dead as they try to cross into West Berlin. No witnesses, you see.

All these years later, it emerges that Lemas and his girlfriend had, respectively, a son and daughter who have now joined forces to demand a Parliamentary inquiry and possible court case to establish liability for their parents’ deaths. Back in the day, a D-notice or similar would have silenced them, but the Cold War is long over and transparency is the name of the game.

The new MI6, in its ghastly riverside fortress at Vauxhall Cross, exhibits all the faux matey-ness and frantic backside-covering that you would expect. Guillam’s interrogators – Laura and Bunny (the latter is a man) – are almost parodies of awfulness, and one cheers on Guillam as he gamely lies to them and seeks to protect ‘old Circus’ from the consequences of its actions.

If Laura and Bunny are a little difficult to take entirely seriously, so is the notion that the Circus ‘safe house’ in Bloomsbury, set up specifically for the Lemas operation, is still, half a century later, being paid for, as is its live-in housekeeper. Even Yes Minister never suggested this sort of disregard for public money.

Quibbles aside, this is a very good book, and even the unlikelihood of the continued existence of the safe house is mitigated somewhat when Laura is confronted with the, to her, ancient dials and switches of its communications equipment, her bafflement an apt metaphor for an inability to understand the context of the case she is investigating.

Quibbles aside, this is a very good book, and even the unlikelihood of the continued existence of the safe house is mitigated somewhat when Laura is confronted with the, to her, ancient dials and switches of its communications equipment, her bafflement an apt metaphor for an inability to understand the context of the case she is investigating.

Between 1963 and 2017, of course, we learned, in Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (1974) that the Circus had a much bigger problem than Fiedler, in that its deputy chief is a deep penetration Soviet agent, a ‘mole’, exposed by the formerly retired George Smiley.

How have we come this far without mentioning Smiley? Guillam was his right-hand man in the mole investigation and went on to greater things in the secret service.

This is almost certainly the last fictional outing for the old Circus and its cast of almost mythic characters, as well-known to le Carré fans as Achilles, Ajax, Helen, Menelaus and the rest. The unimaginative but ambitious Percy Alleline, the sinuous Bill Haydon, manipulative head of the service Control (‘M’ in the James Bond books), the great survivor Toby Esterhazy and Smiley himself, the Merlin/Gandalf figure. Such a mythos of deep-laid characters and storylines, means that ‘each individual’s story, however ephemeral and petty it may seem on the surface, is conjoined with timeless mythic forms’, according to John Carroll in The Wreck of Western Culture: Humanism Revisited (Scribe, 2004). His words help illustrate why the current State-backed campaign to ‘tackle stereotypes’ is so woefully misguided.

Smiley, it turns out, is still with us, living in Germany. He and Guillam dine in an old coaching inn (good choice; German food and drink can be excellent for anyone who can be bothered to investigate them) and we learn, as all the reviews have picked up, that the master-spy has always been a Euro-fanatic, but has somehow never mentioned it in any of the previous books in which he has appeared. ‘If I had a mission … it was to Europe.’

All tripe, of course, and we know this is le Carré speaking, not Smiley. How odd that it doesn’t really matter. In Future Rock (Panther, 1976), David Downing imagines an episode of The Virginian (a Western TV series, for you young’uns) in which a UFO lands, a huge budgerigar emerges, offers a character a light for his cigarette, returns to the flying saucer, takes off and the rest of the episode continues in a conventional way. ‘The plot line has not been altered, yet, in a couple of seconds, with an absolute minimum of dialogue, the character … has been totally destroyed and so has the whole series.’

You may have expected le Carré’s having briefly turned Smiley into a ventriloquist’s dummy to have fatally damaged A Legacy of Spies. It doesn’t.

The Cold War was ‘cold’ only in that the feared exchange of strategic nuclear weapons never took place. It was bloodless only in that there were comparatively few casualties in Western Europe, North America, Japan and Australasia, but there was colossal loss of life elsewhere, possibly running into the millions: in Korea, south-east Asia, the Middle East, Africa and Latin America. It has been said that this last region was where the west won the Cold War, mainly in the 1970s, with terrible suffering inflicted by some quite repulsive allies, including Videla, Stroessner, Duarte and – No hace falta decir nada – Pinochet.

In light of this, isn’t it deeply western-centric to get worked up about the demise of Lemas and girlfriend, a couple of middle-class Brits?

Maybe. But as Stalin said, a million deaths is a statistic, only one death is a tragedy. Or two, in this case.