(I’ve engaged in a lot of Christian metaphor and allusion, lately. In my defense, we’re coming out of one of the two big Christian seasons. I also can’t help but acknowledge Christianity as the primary spiritual reference point in our culture: it’s the water we swim in, like it or not. Please forgive me at least one more Christian-centered post, peppered with cheerful heresy.)

At Christmas, someone at the Catholic church down the street from me had left out several Spanish-language pamphlets, explaining how to pray a Nativity novena. Curious (and always interested in a chance to brush up my Spanish), I took one.

Each day considers a different aspect of the “excesses of [Jehovah’s] love”, through the Nativity. Specifically, it details a particular mystic’s private revelations and “direct experience” (your mileage may vary, of course) of not just the Christ-child, but the Christ-fetus.

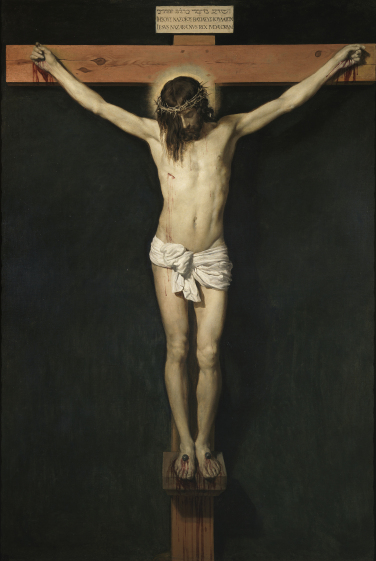

You think that sign says IESUS NAZARENUS, REX IUDAEORUM but it is actually a map legend and says YOU ARE HERE

You think that sign says IESUS NAZARENUS, REX IUDAEORUM but it is actually a map legend and says YOU ARE HERE

(I know, you think this is a novena about abortion. I promise it’s going in a completely different direction. Sit tight.)

Pop psychology tends to argue that the womb was idyllic: peaceful, warm, quiet, still, a place where all your needs are provided for. But this novena points out something I have only ever seen argued in Buddhist texts: the womb is actually a place of intense suffering.

You can’t breathe. You’re filthy. It’s dark. You can’t move. It’s loud: your mother’s heartbeat, digestion, breathing, and voice all echo through. When your mother exerts herself or even bends the wrong way, you are wracked with terrible pain.

With that in mind, the novena (which, at a glance, bears no nihil obstat notice) draws an analogy between the Crucifixion and Christ’s experience in the womb. Both are characterized by immobility, suffocation, pain, blood, and uncertainty.

Conventional Christian theology holds that the Crucifixion was the single greatest sacrifice, but I would argue that it was in fact the Incarnation: infinite spirit’s descent and temporary imprisonment in limited matter, and its (apparently voluntary) experience of a body and mind that will invariably experience pain, loss, and death.

The Crucifixion, then, becomes an allegory for the experience of being alive in the world: the Soul, stretched wide and tall across the Tree, its beating bleeding heart in Tiphereth, pinned down yet still irrepressible. Even death cannot kill it (no matter how much it suffers …!).

There’s something in you that can’t die, and I hope that freaks you out a little

There’s something in you that can’t die, and I hope that freaks you out a little

My own experiences are unprovable, but mirrored through many of the world’s spiritual traditions. They hold that none of this is unique to Christ. You, too, have an undying essence. It, too, is bound to the Cross, wrapped up in the world of matter and conditioned existence, experiencing tremendous pleasure and tremendous pain in turn.

(A question, posed to the suffering Christ on Good Friday: “Does it hurt?” The response: you tell me.)

If you take this as read (and you shouldn’t, necessarily), then there are a ton of questions this opens up. What is the purpose of incarnation? Is it possible to mitigate pain and amplify pleasure in this incarnation, or is incarnation to be avoided at any cost? And in the words of a notable Vodouisant (in his 1980 meditation on the transmigration of the soul and the doctrine of the eternal recurrence): how did I get here?

All of these are worthy questions. Lately, my answers differ from day to day. I hope to explore them with you.

Share this: