Sujata Massey is the award-winning author of the Rei Shimura mystery series set in Japan, and of suspense and mystery fiction set in late British colonial India. In the fourteen novels that Sujata has written over the last twenty years, she’s been interested in sharing the experience of other places, and her new book, The Widows of Malabar Hill, which is coming out in January, is about a Zoroastrian Indian woman – a tiny minority within the country – who is even more different as she’s one of the country’s first women lawyers in early 20th century Bombay. These exotic settings and storylines give a hint of the intricate threads in Sujata’s own life that have led her to make her home in a Victorian summer cottage in the Wyndhurst neighborhood of North Baltimore.

Sujata Massey is the award-winning author of the Rei Shimura mystery series set in Japan, and of suspense and mystery fiction set in late British colonial India. In the fourteen novels that Sujata has written over the last twenty years, she’s been interested in sharing the experience of other places, and her new book, The Widows of Malabar Hill, which is coming out in January, is about a Zoroastrian Indian woman – a tiny minority within the country – who is even more different as she’s one of the country’s first women lawyers in early 20th century Bombay. These exotic settings and storylines give a hint of the intricate threads in Sujata’s own life that have led her to make her home in a Victorian summer cottage in the Wyndhurst neighborhood of North Baltimore.

Sujata’s father came from India and her mother from Germany. After they met in England, they had fall-outs with both families who didn’t want them to marry outside of their culture. But they did – and happily were forgiven, and their three daughters are welcome whenever they visit India and Germany. Sujata was born in England, and she describes this as an invisible marking that made her immigration experience quite different from that of her parents.

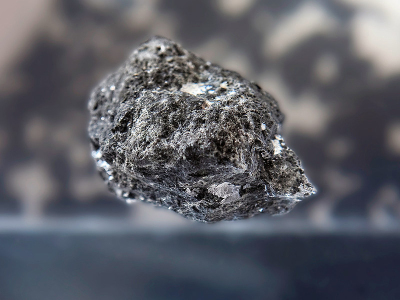

It was his scientific specialty in geophysics that facilitated Sujata’s father getting a visa for the whole family to come first to California and then to Pennsylvania for work. While working at the Franklin Institute of Science in Philadelphia in 1969, he and others were tasked with examining the moon rocks from the Apollo 11 space mission. He let his daughters hold the plain gray stones in their hands and explained where they’d come from. “I felt special knowing I was one of the first children in the world to touch part of the moon,” Sujata says. “And the moon rocks also express for me the tremendous change in destiny we all had through immigration.”

It was his scientific specialty in geophysics that facilitated Sujata’s father getting a visa for the whole family to come first to California and then to Pennsylvania for work. While working at the Franklin Institute of Science in Philadelphia in 1969, he and others were tasked with examining the moon rocks from the Apollo 11 space mission. He let his daughters hold the plain gray stones in their hands and explained where they’d come from. “I felt special knowing I was one of the first children in the world to touch part of the moon,” Sujata says. “And the moon rocks also express for me the tremendous change in destiny we all had through immigration.”

Sujata was five years old when the family left Newcastle upon Tyne in northeast England to come to the States, and she didn’t want to leave her friends and familiar neighborhood. “I proudly told everyone who asked my origin that I came from England. It may have looked cute – the brown girl with long black braids speaking in a Geordie accent for the first year – but it turned into a long-ranging difficulty for me integrating into school.” Her social situation really became difficult after the family moved to Minnesota in the early 1970s, when her father joined the faculty at the University of Minnesota. “This was the Twin Cities in the 1970s, which meant diverse social contacts in the university world for my parents to enjoy. However, I was ostracized from grade 2 to 12. My foreign name, brown skin, different interests, and refusal to conform were the problem.” The struggle of growing up in a very racially prejudiced school environment changed her forever.

Based on an instinct that the East Coast would be better for her than the Midwest, Sujata moved to Baltimore to study English at Goucher College when it was still an all-women’s school, before transferring to Johns Hopkins University and earning a B.A. in the Writing Seminars. Her instincts about the East Coast were right: “It was easy to make friends at Hopkins, which was very international,” she says.

Sujata’s whole family got green cards very easily due to her father’s desirable immigration status as a scientist in the 1960s. “It was a special time,” she says, “when the U.S. government was eager to build its science capabilities to compete with the Soviet Union. In those days, South Asian immigrants were few and far between – most were doctors or scientists.” It would be many years before Sujata decided to turn her green card status into U.S. citizenship. In 1998, she and her American husband were preparing to adopt a baby from India. “Looking at the immigration paperwork, it became clear that things would go more smoothly for our family if both my husband and I were citizens.” Now, she’s very glad that she did it. She’s active in voting and also supporting candidates she believes in. “My status as a citizen makes me feel safer, given the recent turn of events in this country,” she says. “We are tremendously blessed to have been able to adopt our children, because immigration rules have changed making it more difficult now. I made quite sure that our adopted kids have their certificates of naturalization and U.S. passports so they don’t face the risk of deportation.”

As a naturalized U.S. citizen, Sujata thinks of herself an American who will always stand up for immigrants. She tells the story of speaking on the phone to a tradesman about coming out to do a fix-it job in her house. “In a knowing voice, he said to me, ‘I’m not going to send you any foreigners.’ I stopped him right there and told him that I was a foreigner – my whole household was made up of immigrants – and his comment had offended me. He went even deeper into things, saying that certain immigrants had come into his industry and didn’t know what they were doing and were ruining the business. Of course I cancelled the job. People need to know that just because someone has an American accent, it doesn’t mean that they will be complicit in racism.”

For Sujata, the strangest part of her immigrant’s story is that she realizes she appears to most people as Asian American. She uses that term for herself occasionally. But when it comes down to it, she wonders if that is technically true. “What happens to the German part of me, and the British?” The Victorian summer cottage in Baltimore – the home she shares with the husband from Louisiana whom she met at Hopkins and the children they’ve adopted from India – is furnished with a mix of American, English, and Asian furniture and art. “A real mashup,” says Sujata, “just like all of us.”

For Sujata, the strangest part of her immigrant’s story is that she realizes she appears to most people as Asian American. She uses that term for herself occasionally. But when it comes down to it, she wonders if that is technically true. “What happens to the German part of me, and the British?” The Victorian summer cottage in Baltimore – the home she shares with the husband from Louisiana whom she met at Hopkins and the children they’ve adopted from India – is furnished with a mix of American, English, and Asian furniture and art. “A real mashup,” says Sujata, “just like all of us.”

- More