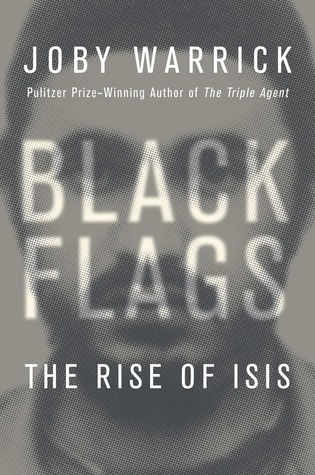

He was a wannabe gangster and a high school dropout who got tattoos, drank and smoked, and sold drugs on the streets of Jordan. His mother was so concerned, she sent him to Muslim self-help classes. There, Ahmad Fadil found a new path. By the time he was killed in a U.S. airstrike in 2006, Fadil-by then known as Abu Musab al-Zarqawi- had lead a new terrorist insurgency in Iraq and Jordan that resulted in tens of thousands of civilian deaths. That group was ISIS. It has cycled through different names and leaders, and it’s replaced al-Qaeda as the terrorist group most likely to radically remake the Middle East.

So maybe his mom should have realized that in the grand scheme of things, having a couple of beers wasn’t that big a deal.

I know that sounds flippant, but all I could think while reading Joby Warrick’s spectacular Black Flags: The Rise of Isis was “what if.” What if Zarqawi hadn’t found religion? What if Jordanian officials hadn’t released him from jail and enabled him to move to Afghanistan? What if the U.S. had stayed out of Iraq- or if they hadn’t bungled the invasion so terribly? Would we still be in the same position?

And could ISIS have existed without Zarqawi? I honestly don’t think so. He was a Charles Manson-like figure, a transformational man who inspired his followers to obey him without question. Early in the book, we meet a Jordanian doctor who visited the prison where Zarqawi was imprisoned in the 90s. He asked the prisoners who needed medical help. None of them answered. None of them even acknowledged him. Instead, they all turned to Zarqawi. The prisoners he nodded at got up from their beds and got treatment. The doctor says he remembered being afraid of the man who held total power over his peers.

Zarqawi was released from prison and made his way to Iraq, where he pledged his allegiance to a decidedly uninterested Osama Bin Laden. He was a nobody until then-Secretary of State Colin Powell named him as a Big Deal Terrorist during his infamous 2003 speech to the United Nations. The speech “transformed Zarqawi from an unknown jihadist to an international celebrity and the toast of the Islamist movement.” Money started pouring in. Recruits, ripe for radicalization following America’s epic mismanagement of the Iraq War, soon followed.

What separated Zarqawi from al-Qaeda leaders was his ruthlessness. His jihad was marked by a brutality that shocked even them. He didn’t limit his attacks to Americans. To him, anyone who didn’t follow his exact strain of Islam was an infidel and therefore fair targets in his deranged war. He beheaded Muslim Shiites and destroyed their mosques. At one point, al-Qaeda even wrote to him and asked him to turn it down. He said he didn’t answer to them, and continued the carnage.

After Zarqawi released a video showing his men beheading an American named Nick Berg (the first of many ISIS execution videos) the U.S. was determined to bring him down. They tried to humiliate him (showing a “blooper reel” of his recruitment videos). They raised the bounty to $25 million-the same as for Bin Laden. They devoted more of their resources to bringing Zarqawi down, and after a few years and some heartbreakingly near misses, they bombed his house. As they pulled his dying body out of the rubble, analysts thought that would be the end of his organization.

But they’re still around, like cockroaches. In 2014 they reemerged on the world stage as they became masters of chaos in western Iraq and Syria. It doesn’t make sense that they’re still around. Most of the popular support they initially cultivated has eroded. They’re butchering fellow Muslims, burning them alive and on tape. They’re “marrying” (raping) young girls. The rising death toll and poor conditions should have scared away foreign recruits. But there’s no sign of their movement losing steam.

This is where the book stumbles for me. While most of the book, detailing Zarqawi’s rise to power and the conditions that allowed for ISIS’s formation were engrossing and matter-of-fact, it loses momentum after his death. Part of that makes sense: it’s a lot easier to write about history than make predictions about the future. But Warrick’s section about the U.S. response to ISIS in Syria is vague. He covers the different arguments people made to Obama-arm the moderate insurgents, bomb Syria, stay out of it, etc. At times, he seemed to be judging the administration for the choices it made, while avoiding any editorialization about what they should have done. Most of his accounting of ISIS’s involvement in the Syria is fuzzy. After hundreds of smart, detailed and analytical pages, it was disappointing for the book to sprint to the finish line. Maybe the book would have been better as a straight Zarqawi biography.

Having said that, Black Flags was a fascinating read. We’re sadly going to be hearing about these monsters for years to come, so you should educate yourself about their inception. Zarqawi’s horrific legacy isn’t going anywhere.

Advertisements Share this: