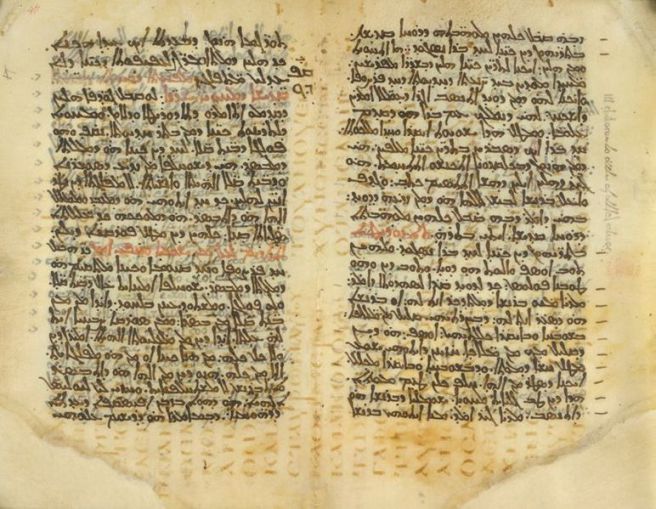

In one of my graduate classes, Research Techniques in Renaissance Studies, I studied the history of scholarship and manuscripts. One of the things I found most interesting was the palimpsest. Since books were made from expensive parchment (animal skin), corrections were not easy to make. Images couldn’t simply be erased with a rubber eraser, nor could pages be crumpled up and started over as they can today with readily available and inexpensive paper. Thus, the palimpsest: ink would be scraped away from the pages, and the correction written on top of what had been scraped away. The process was imperfect and usually left traces of what had come before. Which is why the word palimpsest is so ripe for metaphoric use.

Codex Nitriensis, palimpsest showing text from the twelfth century written over text from the sixth century

Codex Nitriensis, palimpsest showing text from the twelfth century written over text from the sixth century

I love the idea of a palimpsest. Instead of cleanly erasing the past, the outlines of what came before remain visible. It’s honest and transparent. There’s something really beautiful about the complexity involved—of appreciating the remnants of what came before.

Merriam-Webster‘s secondary definition of palimpsest is: “something having usually diverse layers or aspects apparent beneath the surface.” Aren’t the best things in life palimpsests then? When I visited ruins in Rome and Cairo I was struck by the layers upon layers of history there. Arthur Rimbaud’s graffiti on Ancient Egyptian art. Renaissance buildings that incorporated the columns from ancient ruins into their design. So much of modern art is also filled with this sort of thing, if perhaps a little more subtly. We can see the traces of history lurking beneath the surface.

What I find especially interesting is how the meaning of certain experiences or objects in our own lives can take on the quality of palimpsests—in which something is “apparent beneath the surface.” I became acutely aware of this when rewatching a favorite classic film not long ago. I’m descended from a family of old film lovers. My aunt is something of a walking encyclopedia of classic film knowledge. And my mother was quite a fan herself. She especially loved films from the 1940s, films like Mrs. Miniver, Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House, The Late George Apley, and (of course) Casablanca.

In my memories of home, from my earliest days until my mother’s death a little over a year ago, movies like these always seemed to be playing in the background. They acted the way music might in other (more normal?) households. I have memories of cooking Thanksgiving dinner as Claudette Colbert and Clark Gable bantered in It Happened One Night and wrapping Christmas presents to the sound of Monty Woolley’s booming voice in The Man Who Came to Dinner.

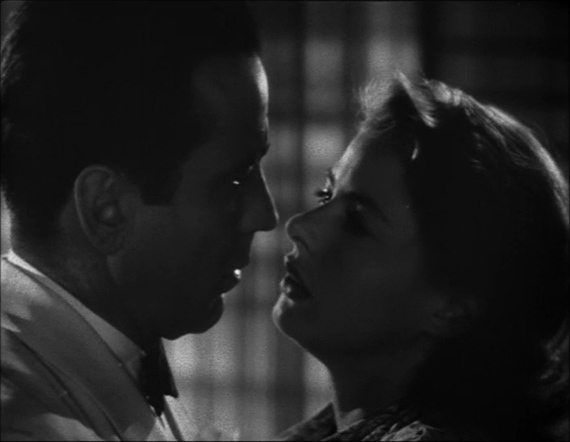

A fraught moment between Rick and Ilsa in Casablanca (1942)

A fraught moment between Rick and Ilsa in Casablanca (1942)

And so, when I catch these movies on TCM these days, they serve as something of a palimpsest—they hint at something “beneath the surface.” Their inherent meaning is still there on the surface. I can appreciate Greer Garson as Mrs. Miniver remaining strong for her family in war-torn England. I am still captivated by the scenes of Ingrid Bergman and Humphrey Bogart gazing longingly into each other’s eyes in Casablanca. But now that my mother—with whom I most closely associate these old movies—has passed away, there is an additional layer of meaning in these films. I love them because I grew up on them and I have grown to love their artistry. But more than that, they are now reminders of a time that’s gone. A reminder of those Thanksgivings listening to Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert. Christmases with Monty Woolley and Jimmy Stewart and Barbara Stanwyck. These films no longer refer just to themselves, but to my memories of watching them in the past.

And it’s odd because, for better or worse, that changes my experience of these films. They carry emotional baggage now that they didn’t before. Isn’t memory funny?

Advertisements Share this: