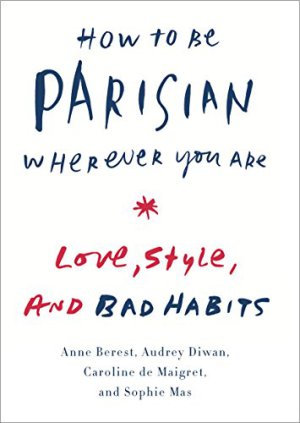

When a friend handed me How to Be Parisian Wherever You Are a couple months ago, she added a caveat. “I laughed a lot while reading it,” she said. “But I’m not sure it’s completely serious?”

This book, a humorous portrait of Parisian women written by four Parisian women, is certainly meant to be funny. But while the portrait may be a bit caricaturish at times, I can only assume that it also contains deep truths about the French psyche. And the one that struck me the most was the recurring theme of independence.

Over the course of the book, a picture emerges of the Parisian woman. While she may complain about many things—the traffic, for instance, or the tourist ploucs invading her beloved city—she seems to take full responsibility for herself. She is strong and self-reliant; she is who she is.

Some of that independence reads like self-protection, the kind of reactionary independence you vow to achieve after one too many bad breakups:

“Over the course of your various liaisons—and incidentally all your not-so-glorious moments—you have learned to truly know yourself, to be strong and independent, to get by on your own,” the authors write.

Similarly, among a list of Parisian aphorisms intended “to be read out loud every night before going to bed, even when inebriated” is “Be your own knight in shining armor.”

But at other times, this independent streak seems much more noble. “You alone are responsible for what happens to you,” the authors declare during a particularly poignant vignette. The implication is that life moves fast; it’s easy to get swept up in your social life and career and to lose your way, if you don’t remember that you are in control of your own destiny and in charge of making your life a good one.

So take advantage of life’s pleasures and savor each moment, they advise. “Take the time to take time because nobody else will do it for you.”

Anne Berest, coauthor of How to Be Parisian Wherever You Are with Audrey Diwan, Caroline de Maigret, and Sophie Mas

Anne Berest, coauthor of How to Be Parisian Wherever You Are with Audrey Diwan, Caroline de Maigret, and Sophie Mas

Reading this, I was struck by how foreign it felt. My sense is that we don’t take full responsibility for ourselves in North American culture: We get in the habit of complaining about the things we have to deal with and the things we wish we had, forgetting that many of these are within our control to change. In short, we (and I’m including myself here) can fall into a victim mentality.

But the Parisian woman seems to refuse to be a victim of her circumstances, chosen or not. While American women are bemoaning their big noses or thick eyebrows, French women seem determined to be elegant in spite of them—or because of them. While Americans are obsessing over fixing their faults, Parisiennes seem to self-improve at a more leisurely pace, one that involves far more acceptance of who they are today.

Why does the Parisian woman have such a formidable presence? Maybe it’s her effortless beauty or her expertise at seduction, other subjects treated in the book. But part of it must be her radical self-responsibility: It puts our little gripes and insecurities to shame, and that’s a bit unsettling.

Advertisements Share this: