In a number of contemporary artists whose works deal with the digital — the so-called post-internet artists — a marked, almost frightening feature is their tendency towards violence.

Post-internet art reflects a certain undercurrent of violence without being didactic about its source.The figure, which had been largely absent from contemporary art for the past few decades, has returned, but only to be pulled apart, dissected or made to disappear — not with any visible bloodshed or abjection, but clinically, echoing in style the unreality associated with the digital. This return to the body as a subject of hostility suggests that the proximity on the Internet to representations of extreme violence is a kind of imbrication — an unresolved culpability from those watching toward what’s seen.

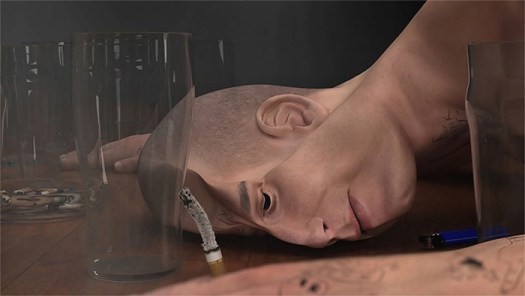

Ed Atkins, Ribbons, 2014

Ed Atkins, Ribbons, 2014

The main characters of Ed Atkins’s digital videos, for example, are cadavers or hard-drinking, tattoo-laced men who clutch glasses of whiskey and cigarettes in desperate need of being ashed. In Ribbons (2014), a head deflates as if perforated by some invisible hand. In Us Dead Talk Love (2012) and Those Warm, Warm, Warm Spring Mouths (2013), the figures ruminate poetically on being dead. The disembodied head of Us Dead Talk Love mourns, specifically, an eyelash stuck in foreskin, while images of statues, hair and eyes go by — a digital dismemberment of the body.

The viral marketing campaigns of ISIS are only the most recent example of how the Internet links us to situations of extreme violence, offering us a unique means to become aware of them.

This is something that Hito Steyerl, in both her videos and her writings, has repeatedly pressed: the connection between the experience of digital media and the physical violence of the world. Suggesting the culpability between the passive Internet user, consumer or spectator and the violence wrought by political and economic inequities, she refuses to bracket off artistic production from the economy and political situations that support it.

Hito Steyerl

Hito Steyerl

Her video In Free Fall (2010) in particular demonstrates how sites of apparent digital illusion are tied to the real world. She traces a specific Boeing passenger plane that had been sold to the Israeli air force in the 1970s, where it took part in hostage rescue missions against the PLO, to a junkyard where it was bought by a special effects team. It is, in fact, the plane in Speed that Keanu Reeves blows up. What was left of the plane after the movie’s filming was then sold to China to make DVDs. The spectacular violence of Speed, which viewers can revel in as consequence-free entertainment, proves to be part of a wider material network of real violence and the precarization of labor.

We do not actually lose our bodies, even if we watch immaterial representations of them.The on-site experience of watching the videos — in a line of inquiry derived from the 1970s — focuses attention not only on the immaterial projections but on the seated and viewing bums as well. Atkins deliberately makes the experience of watching his videos physically charged, with their aural and visual impact pegged up to full blast.

In many ways, the abstraction of the affronts to the body perhaps accounts for the widespread popularity and resonance of post-internet works: They reflect a certain undercurrent of violence without being didactic about its source. It also speaks to the generalized existence of trauma online, of viewing actual deaths and stories about massacres and war in the context collapse of the internet. Violence is general over the world, and navigating the Internet as avatars makes it impossible to deny that we are within it.