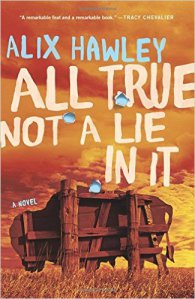

All True Not a Lie in It. Ha! Daniel Boone is one of the most picked-over commodities in pioneer pop culture, (though admittedly he hasn’t had a major spike in interest since Fess Parker’s TV Boone had ‘60s kids sporting coon-skin caps). If there’s a truth left below the varnish of 250 years of mythologizing, I’m not sure we’d be able to tell. Nevertheless, Alix Hawley, in her award-winning debut book, gives us a Boone that feels like a fully human figure, full of dreams and regrets and certainly someone who carries a spark of a larger truth.

All True Not a Lie in It. Ha! Daniel Boone is one of the most picked-over commodities in pioneer pop culture, (though admittedly he hasn’t had a major spike in interest since Fess Parker’s TV Boone had ‘60s kids sporting coon-skin caps). If there’s a truth left below the varnish of 250 years of mythologizing, I’m not sure we’d be able to tell. Nevertheless, Alix Hawley, in her award-winning debut book, gives us a Boone that feels like a fully human figure, full of dreams and regrets and certainly someone who carries a spark of a larger truth.

The pieces of the historical Boone are here. There’s young Daniel and his family chafing against the strictures of a Quaker community in Pennsylvania. There’s an older Daniel moving to North Carolina’s Yadkin Valley and reluctantly taking up farming. Boone the soldier in the French and Indian War. Boone the family man. But this Boone blossoms when he takes off for Kentucky with a small group of companions and calls it heaven – despite being captured by Shawnee, twice robbed of the pelts he collects during long seasons of hunting, and spending more than a year wandering. “I want to believe that this is Heaven now just here,” Boone the narrator says. “Is there any great wrong in wanting Heaven now?” (118)

The pieces of the historical Boone are here. There’s young Daniel and his family chafing against the strictures of a Quaker community in Pennsylvania. There’s an older Daniel moving to North Carolina’s Yadkin Valley and reluctantly taking up farming. Boone the soldier in the French and Indian War. Boone the family man. But this Boone blossoms when he takes off for Kentucky with a small group of companions and calls it heaven – despite being captured by Shawnee, twice robbed of the pelts he collects during long seasons of hunting, and spending more than a year wandering. “I want to believe that this is Heaven now just here,” Boone the narrator says. “Is there any great wrong in wanting Heaven now?” (118)

When he finally does return home he discovers a new child in the cradle, something that only adds to the complications of reestablishing a relationship with his wife, Rebecca. Eventually they work their way back to tenderness, but Boone is no more of a farmer than he ever was, and soon the whole family is heading back to the Cumberland Gap to blaze the trail for an expansion of settled Virginia. The high hopes of the first part of the book come crashing down when the party is trapped in a valley and some, including Boone’s son, come to a bloody and tortured end at the hands of Cherokee.

If Hawley’s book were a standard pioneer tale, the second half would relate Boone’s success in overcoming, conquering the wilderness, and settling the land. There’s plenty of that to tell in the historical record, but nothing in All True goes the way one would expect. The intoxicated dreamer with a musket, smitten with the happy hunting grounds of Kentucky, is replaced by a much softer Boone in the second half – one who is haunted by the ghosts of a lost son and brother and who is mocked and scorned by the men he has led when they are taken into a long captivity by the Shawnee.

There’s plenty of that to tell in the historical record, but nothing in All True goes the way one would expect.

Hawley does a deep dive into the Shawnee culture and opens the possibility for some real relationships between the colonial and indigenous characters, particularly between Boone and Chief Black Fish, who adopts Daniel as the replacement for a lost son. Hawley’s Boone has a light spirit that is alternately puckish and pugnacious. He earns a level of respect within the tribe and the book ends only as change is coming again as the power dynamics shift on the frontier.

Hawley does a deep dive into the Shawnee culture and opens the possibility for some real relationships between the colonial and indigenous characters, particularly between Boone and Chief Black Fish, who adopts Daniel as the replacement for a lost son. Hawley’s Boone has a light spirit that is alternately puckish and pugnacious. He earns a level of respect within the tribe and the book ends only as change is coming again as the power dynamics shift on the frontier.

Meanwhile, Boone’s legend is growing. There is a sense that another figure is living in the stories now being told about him back East and in London. “Everyone knows my story,” Boone reflects at one point. “Everyone but me, as I think.” Boone has been undone in the second half, his Kentucky Heaven now a place of ghosts and broken dreams. “I feel myself a vacant house. I have nothing.” (303).

Hawley has done a miraculous thing in this well-written book. She has re-wilded the early colonial frontier and populated it with visionaries, mercenaries, and troubled souls. She has also, through the extended scenes in the Shawnee camps, taken stock of the native culture that was receding yet still vital. In that, the book resembles Philipp Meyer’s 2013 novel The Son, which worked the same magic for the Texas frontier by including an extended section featuring a Comanche capture.

Hawley has done a miraculous thing in this well-written book. She has re-wilded the early colonial frontier and populated it with visionaries, mercenaries, and troubled souls.

This is not an easy romanticism that Hawley gives us, but it is a romanticism. There is something pulsing and singing through this land that inhabits these characters. Larger forces and deadly vices are conspiring to disenchant the land, though, and it’s not clear if Boone and the others will be heroes or villains in the end. The Boone that Hawley creates is certainly not sure. Part One of his story is called “When I am Good” and Part Two is “When I am Not.” Is his narrative that easy? I’d be tempted to say ‘no’ but then again, this is all true. Not a lie in it.

All True Not a Lie in It: A Novel

By Alix Hawley

Harper Collins, 2016

372 pages

Advertisements Share this: