“The morning Claire Limyé Lanmé Faustin turned seven, a freak wave, measured between ten and twelve feet high, was seen in the ocean outside Ville Rose” (3).

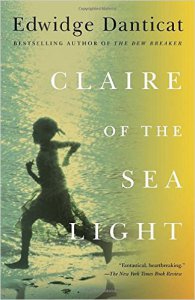

A girl, a birthday, a seaside village, a wave: these are the things which begin Edwidge Danticat’s novel Claire of the Sea Light, and they are the things which persist, wrapping themselves around each other in tighter and tighter knots until they are finally pulled tight at the close of the novel.

The book begins with the disappearance of a little girl, Claire Limye Lanme Faustin, on the evening of her seventh birthday – a day marked by dozens of small and large tragedies, which Danticat notes with the beginning of each chapter of the novel. The novel is pushed forward by the mystery of Claire’s disappearance, and her silence. As the story unfolds the village of Ville Rose comes to life, as Danticat tells the story of a half dozen of its inhabitants, tightly layered like the petals of the same rose which gives the village its name. Along the way, Danticat beautifully depicts life in contemporary Haiti; the villagers lives are touched by gangs, wealth, and poverty, by death, and birth and the sea. It is a portrait both of the pains of leaving and the complications of staying, of the need to speak the truth and the need to remain silent. Each of the chapters focuses on a different lens of the narrative, but each speaks to the others in a complicated, winding dialogue which only begins to make sense at the very end, when Claire’s voice ties the story together.

Beyond the beauty of the layered narrative, in Claire of the Sea Light Danticat beautifully discusses the challenges of both femininity and masculinity, giving each their own weight and space within the story. Particularly moving was Max Senior’s monologue on fatherhood, when faced with the child his son fathered violently, through sexual assault. Danticat writes:

“Let her try to raise a boy and help him become a man. Let her teach him how to tie his shoes, to shake hands properly. Let her show him how to swim, how to fly a kite. Let her show him how to sharpen a blade, to shave or otherwise, how to defend himself when attacked. Let her teach him to read and write and tell him all kinds of stories, the true meaning of which he never seemed to understand. Let her feel proud, then ashamed of him, then proud again… Let her wish for him to be another kind of son and for her to another kind of mother. Let her see what it’s like to protect him from even his worst desires, to keep them from tainting his life forever. Let her try to show him the difference between right and wrong” (184).

There is a beauty here, and a complexity, which mirrors Danticat’s writing on parenting in her short story collection Krik? Krak!, in which mothers suppress the wills and desires of their daughters in order to protect them, perpetuating a social construct at the same moment that they rebel against it. In both Gaelle and Max Senior’s narratives there is a sense of limitation, of infinite love and limited power to shape the lives of their children, of a humanness that makes them flawed parents and which makes their children flawed as well. Perhaps this is the real piece that ties together Danticat’s novel – each character is inherently flawed, inherently human, torn not between right and wrong but between degrees of both. There is a sense of repetition and of doom in this book – the looming wave, the return again and again to a fateful and tragic day – but there is also reconciliation, and love, and good intentions. This is a beautiful and complicated novel, in which each reader can find a piece of themselves.

Buy this book: Indiebound / Amazon

Advertisements Share this: