I first encountered Mary Doria Russell when I read “The Sparrow.” It is one of the most memorable books I have ever read. Beautifully written, it is a science fiction story on the surface; a Jesuit priest who is part of a mission to a planet inhabited by intelligent beings finds himself weirdly seduced by an alien culture and eventually agrees to something he has no way of comprehending. The result is catastrophic for him, both physically and spiritually. He is accused of murdering one of the aliens under very sketchy circumstances and is returned in disgrace to Rome. The book is a meditation on how we view and deal with the “other,” and how actions can be viewed through many different lenses, some distorting one way, some another.

I first encountered Mary Doria Russell when I read “The Sparrow.” It is one of the most memorable books I have ever read. Beautifully written, it is a science fiction story on the surface; a Jesuit priest who is part of a mission to a planet inhabited by intelligent beings finds himself weirdly seduced by an alien culture and eventually agrees to something he has no way of comprehending. The result is catastrophic for him, both physically and spiritually. He is accused of murdering one of the aliens under very sketchy circumstances and is returned in disgrace to Rome. The book is a meditation on how we view and deal with the “other,” and how actions can be viewed through many different lenses, some distorting one way, some another.

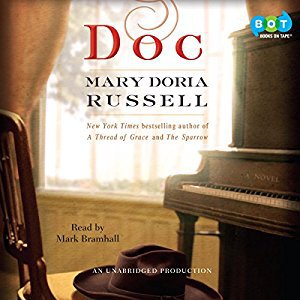

So when my husband recommended “Doc,” I was eager to read it. Apparently Russell is as versatile a writer as Jane Smiley, because “Doc” is as different from “The Sparrow” as can be imagined. It’s a fictionalized version of the life of Doc Holliday, the famous gambler and gunslinger of Dodge City, Tombstone, and the shootout at the OK Corral.

“Doc” is as beautifully written as “The Sparrow,” and in some ways as evocative and touching. Russell did her research, reading autobiographies and biographies of the principals and bit players alike, mining contemporary newspaper accounts and the penny dreadfuls, and the surviving letters that passed between Doc and his family and friends.

What emerges is a very different man than the legend of the pitiless gunslinger. Doc acquired his nickname because he was a trained and licensed dentist. Hailing from an aristocratic Georgian family, John Henry Holliday was a well-educated Southern gentleman with rarified tastes in music, art and literature. He also had tuberculosis, contracted from his mother, whom he nursed until her death. He became ill at the age of 22 and died at the age of 38. “Doc” takes us up to the age of 28, when he was still living in Dodge City and before the famous shootout.

The book is an exploration of the man’s friendship with the Earp brothers, the woman who shared his life and bed, Kate Horony, and others, showing him to be a true friend and a kind man who stuck with his profession as much and as long as he could, until the disease destroyed his ability to continue. He gambled to earn money, and spent it lavishly on his friends. Waging what he knew was a losing battle, Holliday stayed true to his upbringing. The stories about the men he had gunned down turn out to be primarily fictions, perpetuated by post mortem accounts penned by people who badly needed money.

I was also fascinated by Kate Horony, his off-and-on lover. Kate Horony was a well-ridden prostitute, a stereotypical figure in Old West literature.

Except Mary Catherine Horony started life as the daughter of a Hungarian-born physician. When Dr. Horony and his wife died within a month of one another in 1867, Kate and her younger sister were left to the care of a lawyer, who seemed not to have cared very much. Kate ran away at the age of 28 and probably became a prostitute shortly thereafter, there being few other positions for women on their own at the time.

Curiously, Russell perpetuates the myth that Kate was the daughter of Hungarian aristocracy, ruined by the fall of Emperor Maximilian of Mexico. Russell attributed to her a facility in many languages and an appreciation of music, art, and the finer things that would have appealed to Doc Holliday’s refined tastes. Maybe Russell knows something I don’t know, or perhaps she just liked the way Kate’s mythic past fit so neatly into Doc’s actual history that she couldn’t resist.

I found myself really caring about the characters in “Doc,” especially Doc himself and Wyatt Earp, so I was all the more startled and displeased by the way the book ended. Chronologically, the story ends before the shootout in Tombstone. After a lyric, heart-wrenching scene where Doc plays the piano for the first time in years, Russell suddenly switches from telling the story from within the characters’ points of view to a summary of what happened to each of the principals in later life. I found this sudden switch from intimate to remote to be abrupt and almost hasty, as though the author couldn’t be bothered with telling the tale to its natural conclusion.

I understand that a sequel is on the way that finishes out Doc’s miserable, pain-racked life to the end. This is no excuse for dumping the reader by the side of the road and telling him that he has to catch another bus. Will I read the sequel? I might, but I ached for Doc’s suffering so completely throughout the first book, I may have to skip Russell’s no-doubt skillful portrayal of his anguished and impoverished death.

Share this: