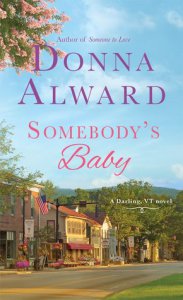

Donna Alward’s migration to the lengthier contemporary (from MissB’s beloved categories) has resulted in hit-or-miss romances. With the third in her Darling, Vermont series, Somebody’s Baby, Alward hits her stride. Like one of Miss B’s favourite categories, Alward’s Her Rancher Rescuer, the protagonists of Somebody’s Baby are young – really young – not the usual put-together super-people that contemporary romances tend to give us, but callow. Because Alward makes them somewhat unlikeable, at least initially, in their callowness, their growth is more believable.

Donna Alward’s migration to the lengthier contemporary (from MissB’s beloved categories) has resulted in hit-or-miss romances. With the third in her Darling, Vermont series, Somebody’s Baby, Alward hits her stride. Like one of Miss B’s favourite categories, Alward’s Her Rancher Rescuer, the protagonists of Somebody’s Baby are young – really young – not the usual put-together super-people that contemporary romances tend to give us, but callow. Because Alward makes them somewhat unlikeable, at least initially, in their callowness, their growth is more believable.

Oaklee Collier is 24 and works in Darling’s publicity department. She is all things FB, Twitter, promoting tourism and local businesses. It’s no wonder Twitter plays a clever, interesting role in the narrative. As a Twitter aficionado, MissB enjoyed this, among many others of the novel’s aspects. Oaklee is texting, tweeting, and being phone-distracted when she hits a mangy dog with her car. Overwhelmed by guilt, hoping to save the dog, she carries him to the local vet’s, where her brother’s best friend and high school “white-steeded knight” works, Dr. Rory Gallagher. When Rory overhears her, as she enters the clinic muddied, bloodied, carrying whimpering doggie, he has the typical rom response to the best friend’s little sister, “Unless he was mistaken, that voice belonged to Oaklee Collier. A complete and utter pain in the ass.”

Somebody’s Baby has a conventional small-town romance feel, but the humour and adorable dog, which Rory convinces Oaklee to foster, kept MissB reading. Alward has always had a smooth, likeable style that appeals to Miss B. But Somebody’s Baby turns into something quite out of the ordinary and delightful. First, there is, as MissB. mentioned, Oaklee and Rory’s realistic youthfulness. They’re paying student loans, have landed first jobs post-college, and carry the psychic wounds of the broken-hearted after their first loves’ the painful ends. Miss B. thought Alward captured two fairly well-adjusted (from loving, supportive homes) young people who have discovered that the world doesn’t always go one’s way. Oaklee and Rory are neither vain, nor arrogant, they’ve simply never suffered before.

Oaklee and Rory have coped with their broken hearts in what appear to be different ways, but, in the end, are about closing themselves off from being hurt. Oaklee isolates herself by focusing on career and being such a workaholic she barely sees her loving parents. No boyfriends, not even that many friends, and work work work it is for Oaklee. Rory is a serial dater, surfing dating sites and out with a new lady every week. After the first two or three dates, however, he politely breaks it off, having warned the lady that he doesn’t do serious or long-term.

And yet, he and Oaklee are friends and it’s not long before their former teen-age friendship-lite is accompanied by genuine affection and attraction. They navigate the attraction well, kissing and flirting, and concluding:

“Neither of us seems to want anything serious. But we do seem to want each other.” Something felt off when she said it, just a niggle of conscience that said she couldn’t take sex so lightly. That it was supposed to be meaningful on an emotional level, and not recreation. But where had that got her for the past two years? Celibate and … emotionally frozen, too.

The above passage is why MissB. loves Alward still and stuck with her longer-contemporary growing pains. Alward understands that the essence of romance is the recognition that attraction and sex are emotionally complicated to two people who are, at core, serious, caring, and honourable. While romance often contains love scenes (Alward’s are definitely on the tame side), it’s never about sex: it’s about commitment. Commitment consists of the giving over to the other of body and heart. To the romance protagonists and genre, these two aspects are inextricably linked. Here, Oaklee is a modern, albeit conservative, young woman, as is Rory, conservative that is, and, while modern mores have moved away from strictures against premarital sex, they haven’t moved away from the idea, even in this initial Oaklee niggle, that it’s “supposed to be meaningful on an emotional level.”

Oaklee and Rory are young, strong, and beautiful. Their bodies are in sync, but their ability to communicate with and understand each other are thwarted by fear and loss. Alward can write a meaningful love scene, but she can also write how the aftermath may be disconnecting and lonely. Because the body-work may be done, but the heart has yet to catch up. Here are Oaklee’s thoughts:

… [Rory] nodded, as if he understood. But he didn’t. She knew he didn’t. Suddenly they seemed very far apart, when only minutes earlier they’d been extremely close … Nothing had gone right tonight. As she got closer to her apartment, she realized it was because neither she nor Rory knew what they wanted. All they knew was that it involved each other.

Oaklee and Rory’s HEA-journey is about learning to love and trust again. They don’t have much to go on, except a mutt, good examples of loving couples, love-mentors in their families and friends, and good will.

Not much is said in romance critique about the key to a loveable couple is the “good will” to take a chance, persist, think things through, ask for advice, and take a risk in communicating the heart. Seems simple, but is frightening. Oaklee and Rory are scared, but have good will and sufficient inner and family resources to take emotional risks. How they do so is funny, endearing, and original and tells romance readers that Alward hasn’t lost her magic touch. Witness this beautiful summary of the HEA-journey from the initial tentative stirrings of the heart to its surety, from first kisses to last: ” … it was definitely the sort of kiss laden with hesitant possibilities and unanswered questions. … They’d had many kisses already, but this one was the best, because all the others had been questions and this one felt like the answer.” The answer to Alward’s Somebody’s Baby, with Miss Austen’s assent, is “there is no charm equal to tenderness of heart,” Emma.

Donna Alward’s Somebody’s Baby is published by St. Martin’s Paperbacks. It was released in April and may be found at your preferred vendors. Miss Bates received an e-ARC from St. Martin’s Paperbacks, via Netgalley.

Rate this:Share this:- More