The day after Kyle was born I began searching for information and answers to my questions about raising Kyle. You’ve probably read the previous post about him, but here is a photo from right after birth.

I asked on one my Facebook groups if anyone could tell me the name of this condition. I remembered what it was from a post in another Facebook group in 2016 but couldn’t remember the name of it right then. A woman who was also a member of both groups reminded me that the condition is called hypotrichosis. When I first posted about Kyle on Facebook people were amazed by him. Lots of people wanted him and others thought I should try to breed more hairless sheep because he was so cute.

Even after a couple days with Kyle I realized I didn’t want him producing more sheep like himself. Sheep have wool and hair for insulation and to protect their bodies from the sun and from insects. Kyle needed a fleece sweater to keep from shivering and on day 2 his ear had started to swell – a sign of frostbite. If I hadn’t adjusted his heatlamp he may have eventually lost that ear. Even at this point when our plan was to raise him for meat I didn’t want any “Oops” pregnancies so on day 3 Kyle became the first lamb I castrated.

I also emailed our state veterinarian during those first couple days and asked him if he’d ever come across hypotrichosis in sheep. He replied that over the years he had seen the condition in a few calves and told me that it could occur in other species but is relatively rare. He also suggested that I contact the Veterinary Departments of a couple universities, where I might find someone more knowledgeable in ovine (sheep) conditions.

I contacted a veterinarian at Penn State a few days later and asked his opinion on whether or not Kyle had hypotrichosis. I had done some research online but I only found a couple articles about it occurring in Polled Dorset and Australian White Suffolk sheep.

This same day I had also asked my local vet to come out for an issue with another sheep and she examined Kyle as well. He appeared healthy in her opinion, but a little warm so we removed his sweater. From then on we gave him a sweater at night but took it off during the day if the weather was somewhat mild. We also talked about other day-to-day issues like what sunscreen would be safe for him (our vet said Waterbabies® would be the best). At this point we planned to raise him for meat and wanted to be sure nothing we used on him would leave any residues in his body.

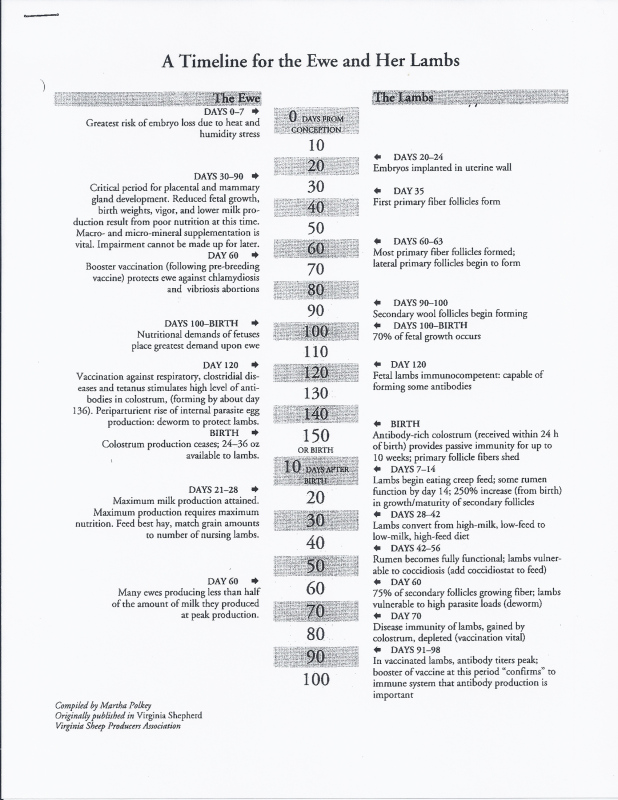

From my description of Kyle, plus the photos I sent, the vet at Penn State agreed that congenital hypotrichosis was a very likely diagnosis. He did say that if Kyle’s dam had a high fever during the phase of follicle development (she didn’t though) it could result in a loss of hair in the fetus (see fetal timeline below).

He suggested several tests, including skin biopsies to determine what the follicles look like and genetic tests of Kyle, his dam and sire (if a lab could be found to run the tests). He also suggested that we could donate Kyle for these tests to be performed during a necropsy. I was not opposed to testing, though I wasn’t interested in euthanizing him for research. The vet tried to find a lab that would be able to do blood tests and also looked for anyone more experienced in genetic diseases in sheep.

Several days later the veterinarian at Penn State sent me an email with contact information for a researcher at Texas A & M University. I emailed her a description of Kyle, along with photos, just as I had with the other veterinarians. She got back to me within a couple days and was able to give me lots of information on hypotrichosis – the condition of which everyone seemed to agree he showed symptoms.

In order for hypotrichosis to occur in an animal, the individual must be homozygous recessive at 3 parts of the hr (hairless) gene. (For a more detailed and scientific explanation, you can read the abstract here.) I looked over the pedigrees of Kyle’s dam and sire to see if there might be any of the same animals that have have introduced the recessive gene into his line. I found 2 sheep, 5 generations back from Kyle that were from the same farm and had similar registration numbers. After talking with our registry I learned that the ram and ewe were both born in 1970. My theory is that they both carried the heterozygous hr gene, which remained heterozygous in each sheep in the pedigree until Kyle.

At this point (last Spring) Kyle was growing well and keeping up with the other lambs. We kept the mamas and lambs in the barn more than we usually do because Kyle got colder more easily and we didn’t want to keep him and Annie separated from the flock.

{coming soon…. more about Kyle over the summer}

Rate this:Share this: