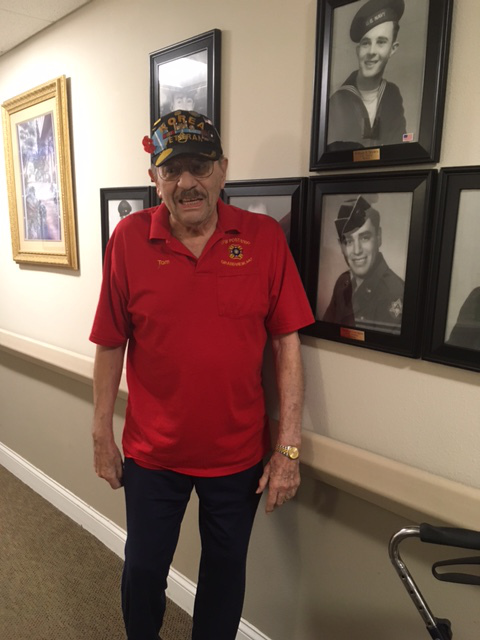

Imagine being plucked out of your quiet, mundane life; taught a valuable skill; and then shipped off to another part of the world. That was the reality for the next three men who shared their stories about their military service in this third article in the series from Carnegie Village.

Thomas Corrigan was a kid growing up on a Navajo Reservation in New Mexico when just 2 years after graduating high school, he was drafted into the Army. He had landed a job doing defense work in Albuquerque, New Mexico and thought that would keep him from being drafted, but “our favorite President, Harry Truman, decided that after two years of giving me a deferment, that he wanted me to serve,” recalls Corrigan. He enlisted and became part of the 30th Topographic Engineering Battalion stationed in San Francisco. His job was to survey in the Alaska Territory during the spring, summer, and fall. The government was sure that if an invasion were to happen that Russia would do so through Alaska and the government needed precise maps of Alaska to prepare. Corrigan said that they would spend up to 20 hours a day in the air surveying and that because it was such a dangerous job they were given combat pay. “We lost like 6 guys every year,” he said. “The down drafts would just suck those helicopters right out [of the air].”

just 2 years after graduating high school, he was drafted into the Army. He had landed a job doing defense work in Albuquerque, New Mexico and thought that would keep him from being drafted, but “our favorite President, Harry Truman, decided that after two years of giving me a deferment, that he wanted me to serve,” recalls Corrigan. He enlisted and became part of the 30th Topographic Engineering Battalion stationed in San Francisco. His job was to survey in the Alaska Territory during the spring, summer, and fall. The government was sure that if an invasion were to happen that Russia would do so through Alaska and the government needed precise maps of Alaska to prepare. Corrigan said that they would spend up to 20 hours a day in the air surveying and that because it was such a dangerous job they were given combat pay. “We lost like 6 guys every year,” he said. “The down drafts would just suck those helicopters right out [of the air].”

Working and living in Alaska was difficult and dangerous. Corrigan even had to kill a bear that invaded their camp. “We had a good big black bear to eat that summer,” laughed Corrigan. He said that his pilot was fascinated with the animals and would chase them with the helicopter. One time he saw a Kodiak grizzly and swooped in to chase and the bear stood up on two legs, challenging the helicopter. “I thought, ‘Engine don’t quit!’” He lived in such remote areas of the territory that the only way to get provisions was from the supply plane drops. “I went 6 months without seeing the paymaster,” stated Corrigan. Of course there was nowhere to spend money where they were located anyway. He also recalls how horrible the mosquitoes were. “You had to cover your body all the time. I’d be on the hill top and turn around and there would be a whole silhouette of me in mosquitoes.”

“At the time I thought I’d make a career out of the service because it was a pretty good deal,” said Corrigan. Tragedy, however, would visit his family and change the course of his life. His father was killed in an auto accident and Corrigan left the service to take over his dad’s position in the trading post on the reservation. That was short lived though because the trading post was losing money as it was not able to keep up with the changing times. “The Indians were modernizing. They were buying trucks and pickups and going to town to get their goods. We still had a couple of wagons for sell. We never did sell those damn things.” From there he went back to work for the government in defense developing a weapon that could be mounted on an airplane that was small enough to allow the plane to land safely on the deck of air craft carriers. He eventually ended up moving to Kansas City to work in radio engineering at King Radio. He also did a lot of delivery of the radios since he had his pilot’s license. “I did a lot of flying for them all over the states of Kansas and Missouri and Illinois. It pays to expand your talents if you can,” recommended Corrigan.

The second gentleman who shared his story was Don Smith. A resident of a little  Missouri town called Deepwater, he joined the Navy in 1951 and was trained in San Diego before being assigned to the ship Samuel N. Moore where he spent 4 years. He was sent to Korea and while serving there his ship was hit but amazingly no one was killed or even severely injured. Smith and his shipmates guarded air craft carriers, bombarded enemy shore installations, and aided in the defense of strategic islands in the Far East. He was then assigned to an amphibious ship called the Henrico that carried troops over to Korea and later to Vietnam. Smith was sent to Treasure Island for a year to receive training in radio and electronics. He also served on a landing ship that also carried troops overseas. His primary responsibilities on the ship were radio and radar. But one of his favorite memories was working with and firing the guns. Life on the ship was never dull either. Smith remembers playing card games and watching movies and the great pork chops they would feed them as well as clambering up to the third bunk which was actually a swinging hammock.

Missouri town called Deepwater, he joined the Navy in 1951 and was trained in San Diego before being assigned to the ship Samuel N. Moore where he spent 4 years. He was sent to Korea and while serving there his ship was hit but amazingly no one was killed or even severely injured. Smith and his shipmates guarded air craft carriers, bombarded enemy shore installations, and aided in the defense of strategic islands in the Far East. He was then assigned to an amphibious ship called the Henrico that carried troops over to Korea and later to Vietnam. Smith was sent to Treasure Island for a year to receive training in radio and electronics. He also served on a landing ship that also carried troops overseas. His primary responsibilities on the ship were radio and radar. But one of his favorite memories was working with and firing the guns. Life on the ship was never dull either. Smith remembers playing card games and watching movies and the great pork chops they would feed them as well as clambering up to the third bunk which was actually a swinging hammock.

Smith also had the opportunity to teach at the Great Lakes naval recruit training center. He worked with 8 different companies and immensely enjoyed being an instructor. He recalled one recruit, a farm kid, that had signed up for the Navy but could not swim. “They kicked him out,” he recalled. Smith would have liked to make a career out of the military and did so for 17 ½ years before a diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis earned him a medical discharge. It was a very difficult time for Smith because of his MS and he had to go on permanent disability in 1970. Over the years he has done his best to stay in touch with his shipmates and still speaks to some to this day.

The last gentleman who shared his story was Jerry White. He was just 19 and living in  Grain Valley when he was drafted in 1953 and went into the Marines. He also was trained on Treasure Island in San Diego for electronics to learn to repair radios. He was sent to Korea where he served for 3 years. Because a cease fire was signed while he was still in boot camp, he never saw active combat in Korea, but there was still a lot of work for him to do. He kept everything up and running from jeeps to radios. He was sent back to the States for advanced electronics training in 1958. After completing that training White was assigned once again to the Far East and for the next several years he traveled extensively throughout the area including Taiwan, Japan, Korea, and Thailand before serving a couple of tours in Vietnam. One thing that really stuck with him from all his travels was how friendly the people were. Another was the crazy temperature extremes that he experienced in Korea. “It is the coldest place I’ve ever been in my life. Temperature wise I don’t know that it goes that bad, but it is the sharpest cold,” White remembered.

Grain Valley when he was drafted in 1953 and went into the Marines. He also was trained on Treasure Island in San Diego for electronics to learn to repair radios. He was sent to Korea where he served for 3 years. Because a cease fire was signed while he was still in boot camp, he never saw active combat in Korea, but there was still a lot of work for him to do. He kept everything up and running from jeeps to radios. He was sent back to the States for advanced electronics training in 1958. After completing that training White was assigned once again to the Far East and for the next several years he traveled extensively throughout the area including Taiwan, Japan, Korea, and Thailand before serving a couple of tours in Vietnam. One thing that really stuck with him from all his travels was how friendly the people were. Another was the crazy temperature extremes that he experienced in Korea. “It is the coldest place I’ve ever been in my life. Temperature wise I don’t know that it goes that bad, but it is the sharpest cold,” White remembered.

White recalled how hard he and his fellow Marines worked, often pulling 12 hour days. He enjoyed getting to know the people he served with who hailed from all over the United States. One particular memory that he cherishes is that of drinking beer. “We didn’t care if it came in a can or a bottle.” One time when he was serving in Thailand the water purification system could not handle the muddy water and beer was all they had to drink. “The Colonel came out and told us, ‘OK you can drink beer on duty, just don’t get drunk.’”

During his tours in Vietnam he was exposed to Agent Orange. “Anybody that was in Vietnam got exposed. They were trying to kill the trees, the bugs, the leaves, the weeds,” said White. He said it was the decision of McNamara, the Secretary of Defense to use that chemical, a decision that would have a life-long impact on White and hundreds of thousands of others who contracted various medical ailments. White was diagnosed with Parkinson ’s disease as a result of his exposure to the toxic chemical known as Agent Orange.

White retired to Yuma, AZ in 1972 after more than 19 years in the Marines. He used the skills he had acquired in the service finally earning a job with Bendix in Kansas City which became Allied Signal which then became Honeywell. He retired from there in 2000 when he went to work for the United States Post Office as an inspector of their sorting machines. That job landed him in New York on that fateful September morning in 2001. He saw the second tower collapse. As a retired Marine he knew that the country was under attack and his response was deep and immediate. “I was pissed off!” he exclaimed. In the immediate aftermath of the attacks and subsequent anthrax attacks, White what deeply involved in making sure that the mail was safe to be delivered. The government took over a Johnson & Johnson plant to accommodate the extra level of screening and radiation treatment for all the mail that was headed to Washington, D.C. “I worked from 5 in the morning to 5 in the afternoon, 7 days a week,” said White. That continued for 3 months. He continued as a private contractor with the Post Office until 2012. “It’s been a good life,” concluded White.

As stated at the beginning of this series, the purpose of telling these stories is to honor the people who sacrificed so much in service to this country and to bring awareness to a worthy cause that Carnegie Village is sponsoring. Carnegie Village is continuing to accept new or gently used suites for men and women who are getting out of the military and need a nice set of clothing for interviews as they seek employment in the civilian sector. August 4 will be the final day of collection. Carnegie Village has been so gracious to facilitate the meetings with these heroes in our community and they cannot be thanked enough for the respect and honor they show these men.

Advertisements Share The Journal: