Thoughts about space and work — specifically creative work — have been bounding in and out of my head since the fall, when I came across and plowed through Shirley Jackson’s two memoirs, Life Among the Savages and Raising Demons. Jackson is best known for her short story “The Lottery,” wherein Rockwellian pastoral cedes, with slow-burning menace, to the spectacle of violence. “The Lottery” is a masterpiece — but her memoirs, epistles of her young and burgeoning family in post-war North Bennington, Vermont. are a delight. Jackson’s wry and bone-dry sense of humor, more subtle in her short stories, is in full force when describing the goings-on of her four children, and she does the neat job of making her husband, in real-life a parsimonious, controlling philanderer, seem, above all, hapless — a city mouse pointing a locked gun at a country rat (reader, he missed).

If you read Life Among the Savages without knowing anything about Jackson, you’d probably come away thinking she was a quick wit and an observational powerhouse — a born Talk of the Town writer, in other words (in fact, it was her husband who wrote Talk pieces). But if you read it knowing that she was a prodigious, successful writer of both short stories and novels (We Have Always Lived in the Castle was a best-seller, and the The Haunting of Hill House is considered by the horror king himself to be a classic of the genre), you might come away struck, as I was, by the utter absence of this side of Jackson from her memoirs.

Life Among the Savages takes place between 1946 and 1951, when Jackson’s fourth and final child, Barry, was born. During this time, she wrote and published two novels and 19 short stories, “The Lottery” among them, yet her memoirs make no mention of writing; in them, she is a selectively capable, drolly harried housewife, one whose days are filled with breaking into her son’s piggy bank to pay the electrician, shepherding her daughter’s 7 imaginary children (housed in a real pram) through department stores, and defending her son and husband against accusations of bullying a schoolmate. In addition to the question of why Jackson chose to omit her professional self from her memoirs, there is also a question of mechanics — with four young children to care for, how on earth did she find the time to write?

The short answer is: she did most of the writing in her head. “A writer is always writing, seeing everything through a thin mist of words, fitting swift little descriptions to everything he sees, always noticing,” she explained, rather sniffily, in her essay “Memory & Delusion.” The actual act of taking pen to paper (or finger to key) occurred on snatched time, in common spaces. Jackson’s children recall her writing in the middle of baking, perched on a kitchen stool or wedged at a folding table in the dining room.

Looked at one way, Jackson’s method seems stressful. No doubt it was — and certainly, it required extreme discipline and mental clarity (perhaps the stimulants Jackson took for her weight helped with this). On the other hand, it really takes away some of the dauntingness embedded in the writing process. To hell with warm-up rituals, the coffee and the patch of sunlight and the ten minute meditation! To hell with Woolf’s dedicated room and 500 pounds a year! Write in your head and get it out when you can. And evidently there was something to this method — for would Jackson’s work have been so brutally economical in language and pacing and plot if she’d had more room to deliberate her choices? In A Room with a View, Woolf argues that Charlotte Bronte’s work would have been elevated had she the chance to travel the world — or at least England — a bit. Maybe so — but Jackson’s case, isn’t it the very narrowness of her stories’ scope — their small, puritanical New England towns and the moral hypocrisy of their inhabitants, the inexorable molding of women into housewives, the blindness of mothers — that renders them so harrowing?

It’s hard to say that Jackson’s existing work would have benefited from Woolf’s room and five hundred pounds. But. But! It’s far easier to say that there would have been more of it. By the time she died, of a heart attack, at age 48, Jackson was suffering from anxiety, depression, debilitating headaches, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, colitis, and such severe agoraphobia that she took to her bed for nearly two years. Many of these were lifestyle-induced, or lifestyle-aggravated — had Jackson’s housewifery been a little less demanding, had there been a bit more built-in support for her writing, who knows how many Lotteries she might have put forth. There isn’t one recipe for great writing, but a girl needs something — a bit of time to herself, or, yes, a damned dedicated room, if she’s to keep producing it.

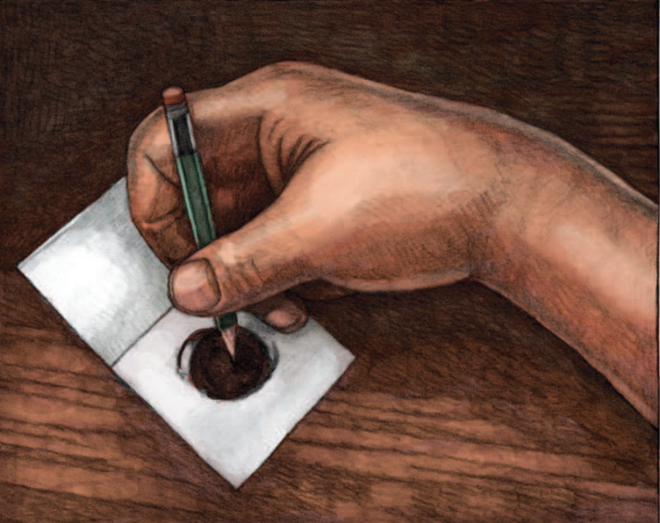

All images from Miles Hyman’s graphic adaptation of “The Lottery,” excerpted here

Advertisements Like this:Like Loading... Related