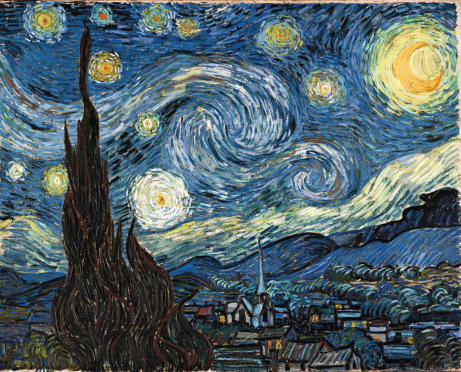

Starry Night, Vincent van Gogh, Museum of Modern Art, New York City

When I have a terrible need of—shall I say the word—religion, then I go out and paint the stars.In many ways, it was just business. Van Gogh made his living by painting so he was sensitive to the market. He painted at least twenty-one versions of Starry Night because they seemed to sell well. That is not to say he was uninspired by his subject. A deeply spiritual man, he found in the stars a great expression of the eternity in his heart, and it just happened to help him to earn a living.

As Terry Glaspey explains in 75 Masterpieces Every Christian Should Know :

Is it prostituting art to earn a living from it?Starry Night is one of those paintings so iconic—we’ve all seen it reproduced so many times—that it is difficult to really see. We have to step back and take a careful second look for it to begin to divulge all its wonder. This image of a small town seen from a vantage point on a hill is not so much concerned with the town as it is with the night sky overhead—a night sky that swirls and swells and spins above us. The painting itself feels strangely alive, as though it were itself an object in motion. The moon and the stars shine and shimmer in the midst of this pulsating vision of the sky, and one cannot help but wonder if, as he contemplated this scene, Vincent van Gogh experienced some sort of mystical vision of the eternal realities behind the earthly beauty. For van Gogh, a believing man deeply frustrated with religious institutions, it was in such visions that he discovered his connection with God. As he once wrote, “When I have a terrible need of—shall I say the word—religion, then I go out and paint the stars.”1 And that is precisely what he has done in this modern masterpiece.

The viewpoint in the painting from which the landscape is seen was the view from van Gogh’s bedroom window. He painted no less than twenty-one canvases of this particular landscape, though Starry Night is the most evocative of them all. The village seen in the painting is his invention, not something he could actually see from his window but rather added to the composition. When van Gogh sent several paintings to his brother so that he could try to sell them, he initially didn’t send Starry Night, evidently considering it less marketable than his others. In fact, he considered it a failure. Time, of course, has proven him wrong, as it has become one of his most popular works.

John 1: 1-5 In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. The same was in the beginning with God. All things were made by him; and without him was not any thing made that was made. In him was life; and the life was the light of men. And the light shineth in darkness; and the darkness comprehended it not. D I G D E E P E R Vincent Van Gogh

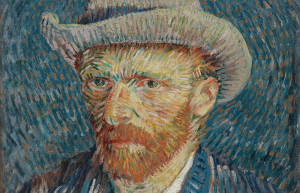

Vincent van Gogh

(1853–90). One of the four great Postimpressionists (along with Paul Gauguin, Georges Seurat, and Paul Cézanne), Vincent van Gogh is generally considered the greatest Dutch painter after Rembrandt. His reputation is based largely on the works of the last three years of his short ten-year painting career, and he had a powerful influence on expressionism in modern art. He produced more than 800 oil paintings and 700 drawings, but he sold only one during his lifetime. His striking colors, coarse brushwork, and contoured forms display the anguish of the mental illness that drove him to suicide.

Vincent Willem van Gogh was born on March 30, 1853, in Zundert in the Brabant region of The Netherlands. He was the eldest son of a Protestant clergyman. At the age of 16 Van Gogh was apprenticed to art dealers in The Hague, and he worked for them there and in London and Paris until 1876.

Van Gogh disliked art dealing, and, rejected in love, he became increasingly solitary. He began to prepare for the ministry, but he failed the entrance examinations for seminary and became a lay preacher. In 1878 he went to the impoverished Borinage district in southwestern Belgium to do missionary work. He was dismissed in 1880 over a disagreement with his superiors. Penniless and with his faith broken, he sank into despair and began to draw. He soon realized the limitations of being self-taught and went to Brussels to study drawing. In 1881 he moved to The Hague to work with the Dutch landscape painter Anton Mauve, and the next summer Van Gogh began to experiment with oil paints. His urge to be “alone with nature” took him to Dutch villages, and his subjects—still life, landscape, and figure—all related to the peasants’ daily hardships and surroundings. In 1885 he produced his first masterpiece, ‘The Potato Eaters’.

Feeling too isolated, he left for Antwerp, Belgium, and enrolled in the academy there. He did not respond well to the school’s rigid discipline, but while in Antwerp he was inspired by the paintings of Peter Paul Rubens and discovered Japanese prints. He was soon off to Paris, where he met Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Gauguin and discovered the impressionists Camille Pissarro, Seurat, and others. Van Gogh’s two years in Paris shaped his personal style of painting—more colorful, less traditional, with lighter tonalities and distinctive brushwork.

Tired of city life, Van Gogh left Paris in 1888 for Arles in the south of France. He rented and decorated a yellow house in which he hoped to found a community of “impressionists of the South.” Gauguin joined him in October, but their relations deteriorated, and in a quarrel on Christmas Eve Van Gogh cut off part of his own left ear. Gauguin left, and Van Gogh was hospitalized. Exhibiting repeated signs of mental disturbance, Van Gogh asked to be sent to an asylum at St-Rémy-de-Province. After a year of confinement he moved to the home of a physician-artist in Auvers-sur-Oise for two months. On July 27, 1890, Van Gogh shot himself; he died two days later.

Despite his deteriorating mental condition, Van Gogh’s time at Arles, in the asylum, and at Auvers proved to be his greatest productive periods. At Arles he painted with great energy the sun-drenched fields and flowers; at St-Rémy the colors of his paintings were more muted, but the lines were bolder and the whole more visionary; in the northern light of Auvers he adopted pale, fresh tonalities, a broader and more expressive brushwork, and a lyrical vision of nature. The sale of Van Gogh’s ‘Irises’ in 1987 brought the highest price ever paid for a work of art up to that time—53.9 million dollars.

Van Gogh’s Starry ReligionGiven this brief background, we can understand why the Romantics still considered neo-Platonism a live option for buttressing a spiritualized view of nature. They were especially enamored by the concept of creation as emanation, with its metaphor of a radiating sun or an overflowing fountain. They even applied the same metaphors to the artist’s creativity. Art was a lamp radiating its own inner light onto the world, a fountain of overflowing emotions. Wordsworth defined poetry as “the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings.” The next major movement after symbolism came to be called expressionism.

The expressionists rejected the Impressionist dictum that the artist should paint only what the eye sees. The expressionist painter Alexej von Jawlensky said, “The artist expresses only what he has within himself, not what he sees with his eyes.” Music historian Donald Grout summarizes the difference: Whereas impressionism “aimed to represent objects of the external world as perceived at a given moment,” expressionism “sought to represent inner experience.”

Gauguin’s Vision after the Sermon, featured below, is not intended to show a realistic scene—note the flat perspective, the red background, the lack of any visible light source. Instead it depicts the idea in the women’s minds as they pray. (They have just heard a sermon about Jacob wrestling with the angel.) As Rookmaaker explains, Gauguin wanted “to overcome the extreme naturalism of the impressionists,” finding ways “to include more than the eye can see.”

In Starry Night Van Gogh’s whirling stars and flame-like trees are likewise expressionistic. As a young man, Van Gogh wanted to become a preacher, but he was turned down by the theology school where he tried to enroll. Undaunted, he trained as a missionary and worked as an evangelist in a poor coal-mining district in southern Belgium. Determined to share the miners’ poverty, he gave away his belongings and slept on the floor. Unfortunately, the missionary school did not appreciate his passion, and he was dismissed. Finally Van Gogh realized that art too can be a means of serving God. His swirling stars and writhing landscape express “a vision that ultimately belongs more to the realm of religious revelation than to astronomical observations.”

At times, Van Gogh said, he would try to paint in a more realistic style. But soon he would feel “a terrible need of—shall I say the word?—religion. Then I go out at night and paint the stars.”

Sources and Resources“Van Gogh, Vincent,” Compton’s Encyclopedia (Chicago, IL: Compton’s Encyclopedia, 2015).

Nancy Pearcey, Saving Leonardo: A Call to Resist the Secular Assault on Mind, Morals, and Meaning (Nashville: B&H, 2010).

Bernard, Bruce, ed. Vincent by Himself: A Selection of His Paintings and Drawings Together with Extracts from His Letters. New York: Barnes & Noble, 2004.

Bonafoux, Pascal. Van Gogh: The Passionate Eye. New York: Abrams, 1992.

Edwards, Cliff. Van Gogh and God. Chicago: Loyola University Press, 1989.

Erickson, Kathleen Powers. At Eternity’s Gate: The Spiritual Vision of Vincent van Gogh. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998.

Naifeh, Steven, and Gregory White Smith. Van Gogh: The Life. New York: Random House, 2011.

Thomson, Richard. Vincent van Gogh: The Starry Night. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2008.

Walther, Ingo F. Van Gogh. Köln: Taschen, 2000.

Terry Glaspey, 75 Masterpieces Every Christian Should Know: The Fascinating Stories behind Great Works of Art, Literature, Music, and Film (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2015).

Terry Glaspey

Terry Glaspey

I’m really looking forward to discussing my book, “75 Masterpieces Every Christian Should Know,” with the members of Literary Life Book Club. I can’t wait to hear your thoughts and perspectives on some of the art, music, and literature you’ll discover in the book. I’m interested in how it speaks to you in your life and the ways it inspires, challenges, or maybe even annoys you! I’ll try to share some “deleted scenes” stuff I had to leave out and will tell a few stories about what I experienced while doing the writing and research. Hope that many of you can join us as we look at he stories behind some truly wonderful art.

Let’s explore together!

Terry

Join the discussion with Terry on Facebook HERETerry Glaspey is a writer, an editor, a creative mentor, and someone who finds various forms of art—painting, films, novels, poetry, and music—to be some of the places where he most deeply connects with God.

He has a master’s degree in history from the University of Oregon (Go Ducks!), as well as undergraduate degrees emphasizing counseling and pastoral studies.

He has written over a dozen books, including 75 Masterpieces Every Christian Should Know: Fascinating Stories Behind Great Art, Music, Literature, and Film, Not a Tame Lion: The Spiritual Legacy of C.S. Lewis, The Prayers of Jane Austen, 25 Keys to Life-Changing Prayer, Bible Basics for Everyone, and others.

Terry enjoys writing and speaking about a variety of topics including creativity and spirituality, the artistic heritage of the Christian faith, the writing of C.S. Lewis, and creative approaches to apologetics.

He serves on the board of directors of the Society to Explore and Record Church History and is listed in Who’s Who in America Terry has been the recipient of a number of awards, including a distinguished alumni award and the Advanced Speakers and Writers Editor of the Year award.

Terry has two daughters and lives in Eugene, Oregon.

Dig Deeper at TerryGlaspey.com

Some of the greatest painters, musicians, architects, writers, filmmakers, and poets have taken their inspiration from their faith and impacted millions of people with their stunning creations. Now readers can discover the stories behind seventy-five of these masterpieces and the artists who created them. From the art of the Roman catacombs to Rembrandt to Makoto Fujimura; from Gregorian Chant to Bach to U2; from John Bunyan and John Donne to Flannery O’Connor and Frederick Buechner; this book unveils the rich and varied artistic heritage left by believers who were masters at their craft.

Some of the greatest painters, musicians, architects, writers, filmmakers, and poets have taken their inspiration from their faith and impacted millions of people with their stunning creations. Now readers can discover the stories behind seventy-five of these masterpieces and the artists who created them. From the art of the Roman catacombs to Rembrandt to Makoto Fujimura; from Gregorian Chant to Bach to U2; from John Bunyan and John Donne to Flannery O’Connor and Frederick Buechner; this book unveils the rich and varied artistic heritage left by believers who were masters at their craft.

Terry Glaspey, 75 Masterpieces Every Christian Should Know: The Fascinating Stories behind Great Works of Art, Literature, Music, and Film (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2015).

Order it HERE today.